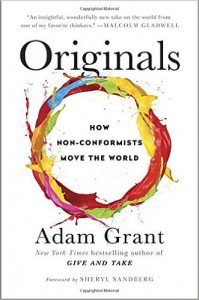

I’m listening to Originals by Adam Grant, and I’m riveted by the part about the “Sarick Effect.” It’s making me wonder if I shouldn’t start changing my approach to adolescent faith formation, like, now.

I’m listening to Originals by Adam Grant, and I’m riveted by the part about the “Sarick Effect.” It’s making me wonder if I shouldn’t start changing my approach to adolescent faith formation, like, now.

The Sarick Effect is Grant’s playful name for the idea that pessimism and doubt can be effective tools for leadership. It rests heavily on the story of Rufus Griscom, who successfully pitched a startup and then sold it to Disney with presentations that led with slides emblazoned with the text: “Here’s why you should not invest in/buy this company.” You can read Griscom’s reflections on the Sarick Effect and an excerpt from Originals here.

“Most of us assume that to be persuasive we ought to emphasize our strengths and minimize our weaknesses,” Grant says. But sometimes, like when you’re dealing with a skeptical audience, it’s actually more effective to lead with your flaws.

He ticks off a bunch of support for this thesis—it disarms the audience; it makes you look smart; it projects that you’re trustworthy; it makes your idea sound better.

For youth ministry, the Sarick Effect has the added advantage of enlivening the New Testament claim that strength is made perfect in weakness (2 Corinthians 12).

There are plenty of skeptics in progressive youth ministries. I’m wondering if the Sarick Effect doesn’t hold the key for accompanying those youth on a journey of transformation in a way that our current progressive posture—which most of the time does not go beyond welcoming professions of doubt and skepticism—does not.

I’ve grown quite comfortable with youth who don’t believe the miracle stories of the gospels actually happened but who want to be part of the church. It’s become a kind of default strategy of mine to affirm to those students that certainty is not required for church membership and to downplay to a degree their overloaded brains can handle the rigors of the life of faith, both mental and physical. One student even asked me, “If I join the church, do I have to, you know, come to church all the time?”

What if I answered that student, “No, and here’s why you shouldn’t.” What if I led with pessimism about the church instead of trying to make a palatable case for it? Because there is a strong case for teenagers skipping church: they need more sleep. They should be outside. Church doesn’t dazzle on a college application. Miracle stories read like fantasy tales. Much of the church’s story and theology feels unfit for the modern world adolescents are preparing to lead.

I’ll bet the skeptical youth can handle our pessimism. She might actually be yearning for it. She’s looking for flaws in the case for faith even as we make it. What if we led with those flaws ourselves? What if our ministries with youth rested as much on the witness of our presence and leadership in communities of faith despite all of their weaknesses, rather than on an attempt to get skeptical teens to grudgingly accept a bare minimum version of Christianity?