For them, land is not a commodity but rather a gift from God and from their ancestors who rest there, a sacred space with which they need to interact if they are to maintain their identity and values. (Laudato si’, 146.)

Read it today

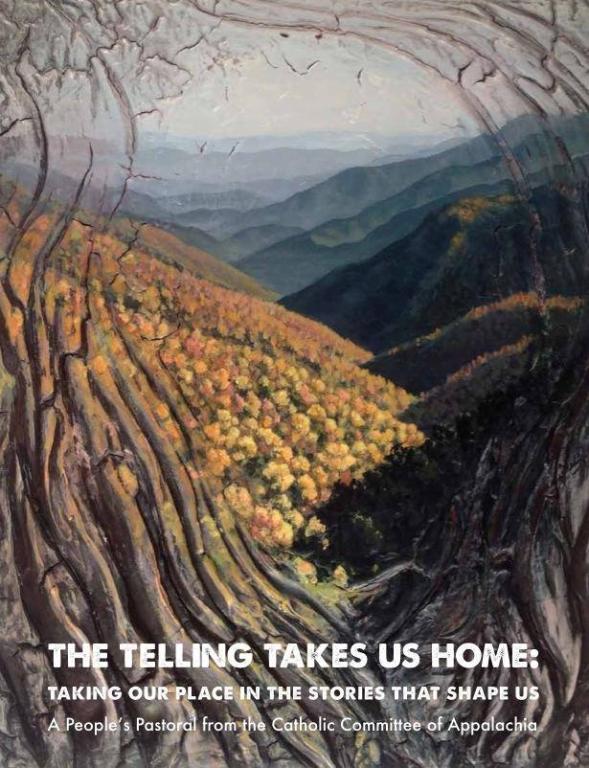

The Telling Takes Us Home: Taking Our Place in the Stories that Shape Us, a people’s pastoral, was released yesterday by the Catholic Committee of Appalachia (CCA).

The Telling is a people’s pastoral; it is an attempt to seek out the marginalized and acknowledge their dignity, being prepared to listen and share in a refreshed dialogue open to the poorest and the weakest.

A people’s pastoral differs from those pastoral letters offered by members of the hierarchy, where instruction, direction, or correction are often its subject, and is addressed to the faithful and all those of goodwill.

A people’s pastoral begins with the people – the outcast, the vulnerable, the poor, and the excluded. This pastoral is not closed to any suffering and will not reject any story – it refuses to ignore the pain and suffering experienced by any part of creation, human or organic.

Composed in free verse style like the two pastoral letters offered by the Bishops of the region, This Land is Home to Me (1975) and At Home in the Web of Life (1995), The Telling beautifully opens by acknowledging the value of story and memory in the safeguarding of individual and communal identity, that is, dignity:

Here in Appalachia,

we are people of stories.

These mountains have heard

the stories we tell,

and have told,

across time and space.

The mountains hold our stories,

and they have stories of their own.Our stories are the lifeblood

that connects us to each other and to this land.

Even those who have left these hills

know the power of the telling

that connects them to home.

The Appalachia, unlike many regions in the United States, is a land of culture and community. It is also a people – and a land – that has been exploited and lied to, damaged and polluted, ignored and forgotten.

In places where injustice is plentiful, and the Church is of the poor, the institutional structures may eventually come to the defense of the oppressed, denouncing sin as it announces the liberating Gospel of Jesus Christ.

At times, however, the Church of the poor chooses to be of the comfortable, and of the rich and powerful. In cases, such as these, which are unfortunately too common today and in our own history, the liberating Gospel of Jesus Christ is found in the quiet whispers of the wind flowing through the trees, in the gentle streams that nourish the land, and on the lips of the fearful poor who, along with the earth, eventually cry out to heaven against the injustice patiently endured often for generations.

We saw this cry all throughout the central and southern regions of America, where the Church as power-structure regularly preferred oppression and violence to loss of power and prestige. Men and women would rise, their actions and suffering striking the consciences of priest and bishop alike, beginning a new chapter on the road to liberation. Remember our past and know what our dignity demands!

The Telling is one manifestation of the poor and the earth’s cry for justice in the United States. It is disturbing to see how rare we will find members of the clergy united with the oppressed in our own land. Where the central and south Americans had Blessed Oscar Romero and the Servant of God Dom Helder Camara, among many, many others, North America in general, and Appalachia in particular, today finds itself primarily relying on the non-bureaucratic catholicism of the people, of the earth.

Where is our Romero, Camara, de Valdivieso, or las Casas?

One Bishop comes to the defense of capitalism in our country and, instead of finding correction, finds another Bishop supporting the cause. It is no wonder so many dioceses in the United States preach justice and engage in alienating hiring practices and elevate “Care for Creation” while profiting from oil and gas extraction through the lethal technique of hydraulic fracturing. Advocating just policies and materializing concrete actions for the poor almost seem to take second place – if they aren’t contracted in their entirety – to expensive garb and ornaments for liturgy to costly precious vessels, from outrageous rebuilding and remodeling efforts to incredible costs for the maintenance of the power-structure of the church which include, among other things, a preference for overpriced priestly formation against the acknowledgement and empowerment of the poor.

The people’s pastoral continues to strive for justice as our central and southern American brethren did, all for the poor.

If we listen to the poor, what is it that we hear? From The Telling:

The increasing unemployment and hopelessness

experienced throughout Appalachia today

is often explained by the media and by politicians

as the inevitable result of a “War on Coal”

initiated by environmentalists

and progressive politicians.

But the creation of a political scapegoat

denies the reality

that mechanization,

natural gas,

and the dynamics of global capitalism

are the true reasons for the loss

of coal jobs in the region,

as coal executives quietly cash out their stocks

while the public is largely misdirected.

We must discern right action through the lies of the powerful.

Reminding us that Francis is inviting us to cherish life before systems, The Telling shares:

The story of Appalachia

is the story of what many call a “sacrifice zone,”

one of the many places of suffering in our world

that are exploited for the sake

of a global capitalist economy

that seeks the “maximization of profit” at any cost

and funnels wealth to those at the top.

Echoing another voice from the land, we’re taught in The Telling:

Capitalism needs its Appalachias.

Capitalism needs poor and oppressed people

because it is in its very nature to create them.

The Telling is a people’s story. There is no way to maintain one’s identity, to know one’s dignity, if one’s story is forgotten. By telling us our story, by reminding us of the suffering we’ve endured under systems of oppression – today that is capitalism – we can remember our calling and our dignity.

We must “hear both the cry of the earth and the cry of the poor” (Laudato si’, 49). In many ways, that cry is recorded in The Telling.

There is plenty we can learn from the efforts of the CCA. Pope Francis reminds me of efforts like theirs when he writes,

Not everyone is called to engage directly in political life. Society is also enriched by a countless array of organizations which work to promote the common good and to defend the environment, whether natural or urban. Some, for example, show concern for a public place (a building, a fountain, an abandoned monument, a landscape, a square), and strive to protect, restore, improve or beautify it as something belonging to everyone. Around these community actions, relationships develop or are recovered and a new social fabric emerges. Thus, a community can break out of the indifference induced by consumerism. These actions cultivate a shared identity, with a story which can be remembered and handed on. (Laudato si’, 232.)

Find out what the CCA is doing and you’ll get an idea of what an imperfect community acting on behalf of justice can achieve. The CCA is helping to remind us of our roots, of our stories, of our lives. Like the indigenous – from whom we may also learn a great deal – the CCA is embracing a truly integral ecology, one that recognizes the divine in all of creation, the only way we can remember the divine in each other:

For them, land is not a commodity but rather a gift from God and from their ancestors who rest there, a sacred space with which they need to interact if they are to maintain their identity and values. (Laudato si’, 146.)

The God who first loved us is not hard to find. God’s vestiges, however, are constantly being destroyed. The poor, where we face the Divine, are denied life. How, then, will we remember that first love?

We must evoke our memory so as not to lose the beautiful experience of that first love which feeds our hope. (Pope Francis, homily, 30 January, 2015.)

The Telling Takes Us Home to that first love, it feeds my hope.

This people’s pastoral was released yesterday by the Catholic Committee of Appalachia and can be downloaded for free on their website: ccappal.org. You’ll also visit their website for information on ordering hard copies of The Telling Takes Us Home, which are available beginning January 1, 2016.

I look forward to listening to the voices in the pastoral more attentively, and I invite you to do the same. We’ll talk about The Telling some more in the future. May we – the people of God – listen and welcome these first words of dialogue.

Perhaps we’ll soon be able to join one another at a common table, ready to engage in true works of mercy for justice on behalf of the poor and the earth.

Until next time,

If you have found the content on Keith Michael Estrada’s “Proper Nomenclature” to be useful, kindly consider supporting the cause with a donation.

Use the button below to donate through PayPal:![]()

Thank you!