ST 4115. Afterlife 5

An Immortal Soul? Really?

I recall one of my graduate school professors, Langdon Gilkey (1919-2004), waxing on the afterlife. “Our theologians are debating which is biblical, immortal soul or resurrection of the body. Well, I’d take either one!”

After posting on “when yer dead yer dead” and the astral body, let’s turn to the very sophisticated concept of the immortal soul which we find most developed in ancient Greece and ancient India.

Philosopher Eric Voegelin (1901-1985) rejects the widespread assumption that the idea of the immortal soul simply evolved over time. Rather, Voegelin believes that about 2500 years ago the divine reality initiated a self-revelation that actually precipitated the emergence of the human soul with its leap forward in our capcity to reason. The human soul was actually created within history as God’s call for us to transcend history. Well, we’ll ignore Voegelin but revisit what happened in ancient Greece at that axial moment.

The Immortal Soul in Ancient Greece

It was February 15, 399 BC. Having been tried and convicted of atheism, Socrates sat in his Athenian prison cell awaiting execution.

Some of Socrates’ friends came to visit, to bid “good-bye” to their revered teacher. The prospect that Socrates would die weighed on them. The visitors were mournful, sad, grieving.

In contrast, Socrates was in quite a good mood. The group decided to engage in philosophical dialogue, much as these neighbors had regularly done in past years.

What is “pure knowledge?” they asked. A ponderous question to ask someone on their deathbed. Well, Socrates hypothesized, certainly pure knowledge must be knowledge of things in themselves. So we must order our “intellectual vision to have the most exact conception of the essence of each thing.” This is what Socrates’ student, Plato, records Socrates having said this in his book, “On the Soul” or Phaedo (Plato Phaedo, 65). Our mind or our soul wants to know.

The Immortal Soul’s Body

But there’s a problem. Something stands in the way of gaining pure knowledge. What is that? The body. All things finite and physical distort the truth, restricting us to our perspective or our interpretation. “The body is a source of endless trouble to us by reason of the mere requirement of food,” complains Socrates.

Food?! What?! Curiously, Charles Darwin might agree. Because we have to eat, the long history of evolution on earth is dominated by predator-prey relationships. To live is to eat. To eat is to kill. Life as we know it is a never-ending struggle for existence. The human race today slaughters and eats 78 billion land animals per year. Kill or be killed.

But Plato does not report that Socrates was reading Darwin’s Origin of Species (1859) by candlelight in his prison cell. Perhaps Socrates simply observed how eating to satisfy the body’s appetites leads to war. Observation led Socrates to philosophy. We remember Socrates primarily by what Plato said.

According to Plato, Socrates said the body is…

“…liable also to diseases which overtake and imped us in the search after true being: it fills us full of loves, and lusts, and fears, and fancies of all kinds and endless foolery, and in fact as they way, the body takes away from us the power of thinking at all…Wars are occasioned by the love of money, and money has to be acquired for the sake and in the service of the body; and by reason of all these impediments we have no time to give to philosophy” (Plato Phaedo, 66).

Soulechtomy? Extraction of the Immortal Soul from its Bodily Prison

Just imagine. Mr. Socrates telling Mrs. Socrates that he’d like to sit quietly in the backyard and think about philosophy. But Mrs. Socrates says, “you can’t do that, Honey. You got to mow the lawn before dinner.”

“But mowing the lawn distracts my mind,” Socrates would whine. “Oh, miserable me! How can I liberate my soul from the physical cares of the body?” Well, something like this.

Death, surmises Socrates, would liberate the soul from mowing the lawn.

“The soul in herself must behold things in themselves: and then we shall attain the wisdom which we desire, and of which we say that we are lovers; not while we live, but after death….the soul will be parted from the body and exist in herself alone [in] the light of truth” (Plato Phaedo, 66-67).

One of Socrates friends, Cebes, adds, “the soul is immortal and imperishable, and our souls will truly exist in another world!” (Plato Phaedo, 107).

Eternal life, according to this view, requires a soulechtomy. Like an angelic surgeon, we must extract the soul from the body. In this case, we keep the soul and discard the body.

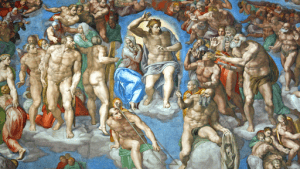

Judgment of the Immortal Soul

All souls are not morally equal. Some of us live according to the eternal principles of justice. Others do not. Our lives this side of death have consequences for the afterlife.

“The good souls of the dead are in existence, and…the good souls have a better portion than the evil” (Plato Phaedo, 72).

Or,

“…he who has lived all his life in justice and holiness shall go, when he is dead, to the Islands of the Blessed (eis makaron nesous), and dwell there in perfect happiness out of the reach of evil; but he who has lived unjustly and impiously shall go to the house of vengeance and punishment, which is called Tartarus” (Plato Gorgias, 523).

Note here that it is not merely the body which distorts the soul’s pursuit of pure knowledge. It is also sin. Immorality in the form of cruelty to the neighbor corrupts not just the body but the soul as well. The consequences of that corruption are carried on into immortality even after the body has been shed. Sin prevents the liberated mind from pursuing pure knowledge even more dramatically than does physicality.

What might a Roman Catholic think about judgment?

What might a Roman Catholic think? Curiously, some Roman Catholics have adopted the doctrine of the immortal soul. And, with it the expectation of a judgment in the afterlife.

“Of this judgment, the Catechism of the Catholic Church asserts, “Each man receives his eternal retribution in his immortal soul at the very moment of his death, in a particular judgment that refers his life to Christ: either entrance into the blessedness of Heaven—through a purification or immediately—or immediate and everlasting damnation. (See Catechism of the Catholic Church, Paragraph 1022).”

A soulechtomy at death is no escape from retributive justice to be exacted on the immortal soul.

The Personality of the Immortal Soul in the Afterlife

If your and my soul are going to face a post-mortem judgment, then it would be necessary that in the afterlife we are the same person we were in this life. Is there continuity?

The Urantia Book of 1955 has gained contemporary disciples who are quite specific about the relationship between our bodily experiences in this life and the personality of our soul in the afterlife. In a new and promising analysis of the theodicy problem, Byron Belitsos posits that the immortal soul beyond death carries our personal evolution in this life with it.

“…conserved elements of real human experience are converted to personal ‘soul memories’ and become a potentially eternal possession of the individual. In addition, our soul is able to survive death (along with the personality and Indwelling Spirit). In fact, the soul is the only purely personal asset that we possess going forward into the afterlife”(Belitsos, 2023, 154).

Our soul’s evolution in this material and temporal world becomes formative for our personality in the afterlife. We might ask: how can an immaterial and immortal soul be affected by, or even defined by, physical and temporal experiences? Evidently, good and evil are properties of the soul and, hence, are eternal values. Certainly Plato thought this to be the case.

Purifying the Immortal Soul in the Afterlife

Perhaps the concept of purification or purgation in the afterlife enters our western tradition here with Socrates. At least as reported by Plato. Upon death we will be judged and sentenced. The measure? Whether we have “lived well and piously or not” (Plato Phaedo, 113). We will be “purified” by suffering the very wrongs we have done to others. Then we will be “absolved” and receive “rewards” for our “good deeds.”

Socrates is describing here what will happen to most of us. Purgatory is the destiny of the average person. But, what about those among us who are incorrigibly evil? It’s not pretty.

“Tartarus is their suitable destiny” where they feel the very pains they had inflicted on their victims. “And they never come out” (Plato Phaedo, 114). Unless, of course, those victims show mercy and forgive them. Like a bobber in a river’s eddy, the evil soul is plunged into Tartarus, bouncing down and up, with no escape until forgiven in eternity by those previously harmed here in temporality.

After bidding “goodbye” and “take care” to his friends, Socrates accepted his court appointed sentence. He willfully drank the cup of poison hemlock and died.

Modern Substance Dualism

The French philosopher frequently dubbed the “father” of the modern mind is René Descartes (1596-1650). Like Plato, Descartes sought immortality through the soul.

Recall that Descartes defined the modern mind by sharply distinguishing between Object and Subject. Today’s university is the child of this father of philosophy. The modern university became divided initially into two colleges. Objectivity became assigned to the sciences. Subjectivity became assigned to the Humanities including art, music, history, ethics, and religion.

Where do we moderns locate personhood? In our subjectivity.

The Subject-Object split provides the background for our question: “how might I survive my death?” Descartes asks, “what do we mean by ‘I’?” Who you and I are, contends the French philosopher, is not determined by our brain, body, or anything physical. Our individual personhood is found in our soul, our mind (Descartes 1641). The soul or mind constitutes our ‘I’, our subjectivity, our reflexive self-consciousness, our perspective on all objective reality.

Perhaps you recall the hinge on which the modern mind hinges, “I think, therefore I am.”

I think, therefore I am.

cogito, ergo sum in Latin

Je pense, donc je suis in French

(Descartes, Discourse on the Method)

Now, this thinking ‘I’ that is you and me is a substance, a mental substance. The physical substance, our body, dies. But, that thinking substance—the self as soul—persists beyond death. Our afterlife consists of thinking as a disembodied substance. Does this sound like Socrates?

Might there be a relationship between the non-material substance that is our soul and the being of God? Descartes meditates on this question.

“By the name God I understand a substance that is infinite [eternal, immutable], independent, all-knowing, all-powerful, and by which I myself and everything else, if anything else does exist, have been created. Now all these characteristics are such that the more diligently I attend to them, the less do they appear capable of proceeding from me alone; hence, from what has been already said, we must conclude that God necessarily exists” (René Descartes, Meditations on First Philosophy, III).

Today’s philosophers largely reject Descartes’ substance dualism. They prefer to embrace materialism. Only material reality is real, accordingly. Let’s get rid of spiritual substances and immortal souls! When the brain dies, the ‘I’ dies with it. That’s all there is. Get over it.

Christian theologians are adapting to the new materialism. Instead of a soulechtomy, Christian theologians affirm a divine act wherein God raises the dead in bodily form. Resurrection of the body replaces immortality of the soul.

Resurrection of the body, not immortality of the soul.

Fuller’s Nancey Murphy rejects substantive dualism in favor or the biblical promise of the resurrection of the body. This position is called ‘non-reductive physicalism’. See what Nancey says, “Does the soul have an afterlife?”

Where have we been? Where are we going?

AFTERLIFE? REALLY?

- The Denial of Death

- Naturalism: When yer dead yer dead!

- Astral Body? Ka? Or Angel?

- Third Day Afterlife

- Immortal Soul

- Reincarnation

- Near Death Experience

- Communication with the Dead

- Absorption into the Mystical Infinite

- Resurrection of the Body

- Heaven

- Hell

Conclusion

Belief in the immortal soul is as welcome at a materialists’ picnic as an invasion of granivorous ants. Materialists spray the philosophical equivalent of Raid whenever Plato’s or Descartes’s dualism appears.

What about the Bible? Here’s St. Paul on resurrection of the body.

“What is sown is perishable, what is raised is imperishable. It is sown in dishonor, it is raised in glory. It is sown in weakness, it is raised in power. 44It is sown a physical body, it is raised a spiritual body. If there is a physical body, there is also a spiritual body” (1 Corinthians 15:43-44).

There is nothing in 1 Corinthians 15 about an immortal soul departing from the body to live in eternity. Nope. St. Paul is promising a resurrection and a transformation of your and my body.

“Death marks an end for the whole person,” writes Roman Catholic theologian Karl Rahner (Rahner 1978, 271).[1] The soul dies. The Christian hope lies not in the immortality of the soul. Rather, hope lies in a future act of God whereby we are raised: body, soul, and spirit.[2]

Both Plato and Descartes are genius philosophers. Pious. Reverent. Hopeful. Yet, their doctrines of the immortal soul do not comport completely with either our materialist philosophers or the New Testament promise of resurrection.

▓

Ted Peters is a Lutheran pastor an emeritus professor at the Graduate Theological Union. He co-edits the journal, Theology and Science, with Robert John Russell on behalf of the Center for Theology and the Natural Sciences, in Berkeley, California, USA. His single volume systematic theology, God—The World’s Future, is now in the 3rd edition. He has also authored God as Trinity plus Sin: Radical Evil in Soul and Society as well as Sin Boldly: Justifying Faith for Fragile and Broken Souls. See his website: TedsTimelyTake.com.

He has just released a new 2023 book, The Voice of Public Theology, published by ATF Press.

▓

Notes

[1] In the tradition of Aristotle and Thomas Aquinas, Pope Benedict XVI nee Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger viewed the soul as the form of the body. The soul is not a separate non-bodily substance. The soul is a substance as the form that animates the body. “Being in the body is not an activity, but the self-realisation of the soul” (Auer 1988, 148), writes Ratzinger in concert with Johann Auer.[2] See: “Reformers’ Beliefs on the Immortal Soul”

References

Auer, Johann, and Joseph Ratzinger, 1988. Eschatology: Death and Eternal Life. Washington DC: Catholic University of America.

Belitsos, Byron, 2023. Truths about Evil, Sin, and the Demonic. Eugene OR: Wipf and Stock.

Rahner, Karl, 1978. Foundations of Christian Faith, tr. by William V. Dych. New York: Crossroad.