ELCA on Christian Nationalism

Here is a must read: We Are Christians Against Christian Nationalism, a document produced by the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America (ELCA). Just what is the Christian Nationalism that we aren’t? Here’s the official definition. Christian nationalism is…

“…a cultural framework that idealizes and advocates fusion of certain Christian views with American civic life. This political ideology, whether explicit or not, includes the beliefs that the U.S. Constitution was divinely inspired and enjoys godly status, that Christianity should be a privileged religion in the U.S., that the nation holds a special status in God’s eyes, and that good Americans must hold Christian beliefs. Proponents range from those who believe the United States should be declared a Christian nation (approximately 21% of the U.S. population) to those involved in more virulent strains that are openly racist, anti-democratic or gang-like. The symbols and ideology of Christian nationalism were widely evident during the Jan. 6, 2021, attempt to throw out certified U.S. election results.”

Presiding Bishop Elizabeth Eaton endorsed the previous ecumenical Christians Against Christian Nationalism (CACN) statement (as I and most of my colleagues have) so that the good bishop could affirm: “We reject this damaging political ideology and invite our Christian brothers and sisters to join us in opposing this threat to our faith and to our nation.”

Like Presiding Bishop Eaton and the statement by the ELCA on Christian Nationalism, I too “reject this damaging political ideology.” And I’m grateful that ELCA leadership has taken a strong stand. But there is a not-so hidden history lurking just below the surface that impells Lutherans.

Lutherans’ Not-So Hidden History

Here’s that not-so hidden history. During the rise of the Third Reich in Germany during the 1930s, the Lutheran witness on behalf of Jesus Christ – and against nationalist idolatry — was mortifyingly weak.

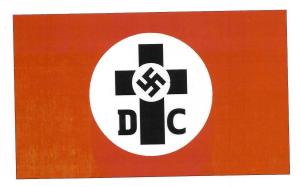

If you cut the pie of Christian leaders into thirds, one third of clergy within the German Evangelical (Lutheran) Church joined the German Christians, Deutsche Christen, the pro-Nazi church. Some of these patriotic churchgoers saw Adolph Hitler as a political savior to rescue Germany from economic chaos, from national humiliation in World War I, from the immorality of homosexuality, and from the poison of alien races.

During the 1930s, Christian symbols and Nazi symbols became intermingled. Each week the propaganda ministry in Berlin would write the sermons to be delivered the following Sunday in Deutsche Christen parishes. Nobody in the ELCA today wants to see a repeat of the Third Reich.

A second third of the Lutheran (and Reformed too) pie courageously stood up to the Nazi regime and established a counter communion, the Confessing Church, die bekennende Kirche. Their rejection of Nazism is not unlike today’s ELCA rejection of American Christian Nationalism. If Jesus Christ is Lord, then Adolph Hitler is not. The Nazis responded by conscripting Confessing Church pastors into the military and sending them to the front lines where they were likely to get shot.

The final third of the Lutheran pie was made up of clergy who sought to separate church life and political life. A difficult and less than admirable task both then and now.

Today’s ELCA wants the whole pie to reject the looming threat to both Christian faith and American democracy, a threat posed by the MAGA-Machiavellian wing within the Republican Party.

Why is the statement of the ELCA on Christian Nationalism important to Lutherans?

Why is the statement of the ELCA on Christian Nationalism important to Lutherans? Because “the ELCA is committed to the common good — not for the good of Christians first — and to working with and learning from others.” Note how the aim of the ELCA commitment is to the common good of the wider society. Over against American Christian Nationalists (ACN) who want to privilege their own religion, the public face of the ELCA is turned toward the common good. I especially appreciate this as an expression of public theology. Recall my working description of Public Theology as conceived in the church, critically refined in the academy, and offered to the wider world for the sake of the common good.

How does the ELCA on Christian Nationalism define it?

How does the ELCA on Christian Nationalism define it? Note in the definition above how for the ELCA drafters ACN is “a cultural framework.” Apparently, it’s not an organization, movement, or school of theological thought, say the ELCA drafters. Further, this cultural framework may or may not be “explicit.” One can silently hold Christian nationalist views, and no one would know. Is this definition precise enough? I wonder.

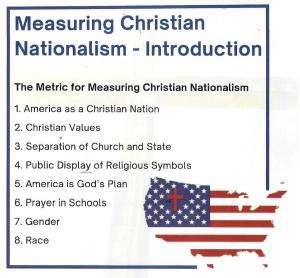

Those views the ELCA identifies as Christian Nationalist include “beliefs that…Christianity should be a privileged religion in the U.S.” In an earlier post on “Measuring Christian Nationalism, Part 1, Christian Nation?,” I attempted to search out actual individuals or groups who assert this. What did I learn?

I found at least one avowed ACNer who holds this view, Stephen Wolfe. In his The Case for Christian Nationalism, Wolfe writes, “It is evident enough that for most of United States history Americans thought of themselves as a Christian people” (Wolfe, 2023, p. 389). So, treating America as a distinctively Christian nation can be heard from the voices of at least one, maybe more, ACNers.

But not from every self-identified Christian nationalist. A Black Christian Nationalist (BCN), in contrast, would be much more nuanced. “From the time Cadillac brought the first slave to Detroit in 1701 to plant crops and construct buildings to the tumultuous 1960s and 1970s, Black people were subjugated by a brutal racist oppressive system,” writes BCNer Shelly McIntosh (McIntosh, 2021, p. 7). If this is what a so-called Christian nation has done to its citizens of African American heritage, then defining America in this way would not attract BCN. So, the ELCA definition does not cover this explicit form of Christian nationalism. Mmmmm? Maybe the alleged “Christian nation” idea is buried in the beliefs of those non-explicit forms of Christian nationalism. In short, this may be a corrigendum in the document. So I ask: How could the ELCA on Christian Nationalism better help us to clarify things?

Let me mention something else pertinent yet not addressed by the ELCA statement. It’s important to note that America’s evangelical leaders are nearly unanimous in support of religious liberty, especially the CACN evangelicals. Evangelicals do not demand that the federal government declare the United States to be a Christian nation. CACNers tell us that CACN holds that “government should not prefer one religion or religion over nonreligion.” This according to Amanda Tyler, who is executive director of the Baptist Joint Committee for Religious Liberty. Tyler pleads for a pluralistic society wherein the government refrains from promoting or discouraging any religious faith. So, let’s not confuse ACN with the historic position of evangelicals on religious liberty.

Thanks, ELCA, for not scapegoating evangelicals!

In my own odyssey over the last couple of years studying the Christian nationalist phenomenon in Russia and America, I have noticed something not mentioned in this otherwise helpful ELCA declaration. What is not mentioned is the way in which progressive Christians are scapegoating evangelical Christians. Progressives justify this scapegoating by conflating evangelicalism with Christian nationalism. I’m delighted that my ELCA colleagues refrained from providing ammunition for anti-evangelical cannons.

But we’re not completely safe from prejudice against evangelicals. By reducing ACN to a vague “cultural framework” that might not even be “explicit,” ELCA thinkers are unable to critically assess what is going on at home among progressives. Worse, the statement waves a menacing flag with this descriptor:

“Christian nationalist ideology asserts itself combatively through culture war topics regarding gender, sexuality, race, and the role of government.”

What might be the implications of this? Could it be the following? If we progressives within the ELCA disagree with our evangelical neighbors on “topics regarding gender, sexuality, race, and the role of government,” are we then justified in demonizing our opponents by calling them religious nationalists? Are we justified in saying — as the ELCA on Christian Nationalism cites — those who do not make progressive commitments are “neither faithful to Christ nor patriotic”? This opening to deny both faith and patriotism to those who disagree with us worries me, frankly.

Should we acknwoledge anxiety at work here?

Like a chaplain engaged in pastoral care, I perceive anxiety at work. Progressive Lutherans in America are fearful of the future. Might we lose America’s great gains over the last three-quarters of a century in civil rights? Gender equality? LGBTQ acceptance? Health care access? Reproductive liberty? The 2024 U.S. presidential election could mark a reversal of all these gains. Ouch!

Anxiety is rife in the world of religious progressives. Might this anxiety lead to resentment (French ressentiment), self-justification, scapegoating, and violence? Might our evangelical neighbors become the targets of this scapegoating?

The antidote to anxiety is an inner soul robust in faith. Faith as trust. To trust in 2024 is tough, I know. Yet, Lutherans are strong when it comes to grasping the value of faith in the soul. Might the ELCA consider taking a pastoral tone to address both its own anxious members as well as the underlying anxiety of the wider culture?

Elsewhere — Does Anti-White Christian Nationalism Scapegoat Evangelicals? and Evangelicals Against Christian Nationalism — I make an attempt to self-critique my own progressive Christian community on this tricky topic. Perhaps this is enough said here.

Howard Thurman and David Brooks on the soul

Getting right on the politics is important, to be sure. But getting right with the soul is even more important. In the New York Times, Black Theologian Howard Thurman (1899-1981) is remembered for writing, “Jesus rejected hatred because he saw that hatred meant death to the mind, death to the spirit, death to communion with his father.” David Brooks then adds, “When you try to deceive someone else, even for your own protection, you end up becoming a deceiver deep in your nature. You end up losing the ability to make moral distinctions.”

We need a faith-filled soul to render political judgments that target the real threat and avoid scapegoating surrogate threats.

Conclusion

I wish to thank my ELCA Advocacy colleagues (whose names I do not know) who produced ELCA on Christian Nationalism statement. The document is prophetic, inspiring, and helpful during this period when so many Americans – Christian nationalists and anti-Christian nationalists alike – feel taunted by anxiety.

PT 3239 ELCA on Christian Nationalism

PT 3200 Christian Nationalism Resources

▓

For Patheos, Ted Peters posts articles and notices in the field of Public Theology. He is a pastor in the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America and emeritus professor at Pacific Lutheran Theological Seminary and the Graduate Theological Union. His single volume systematic theology, God—The World’s Future, is now in the 3rd edition. He has also authored God as Trinity plus Sin: Radical Evil in Soul and Society as well as Sin Boldly: Justifying Faith for Fragile and Broken Souls. He recently published. The Voice of Public Theology, with ATF Press. See his website: TedsTimelyTake.com and blog site, https://www.patheos.com/blogs/publictheology/ .

▓

Bibliography

Alberta, T. (2023). The Kingdom, the Power, and the Glory: American Evangelicals in an Age of Extremism. New York: Harper.

Butler, A. (2021). White Evangelical Racism. Chapel Hill NC: The University of North Carolina Press.

Cooper-White, P. (2021). The Psychology of Christian Nationalism: Why People Are Drawn In and How to Talk Across the Divide. Minneapolis MN: Fortress Press.

Denker, A. (2022). Red State Christians: :Understanding the Voters Who Elected Donald Trump. Minneapolis MN: Fortress.

DuMez, K. K. (2020). Jesus and John Wayne: How White Evangelicals Corrupted a Faith and Fractured a Nation. New York: Norton.

Hendrickson, O. (2023). Christians Against Christianity: How Right Wing Evangelicals are Destroying our Nation and our Faith. Boston: Beacon.

McIntosh, S. (2021). Memoirs of a Black Christian Nationalist: Seeds of Liberation. New York: Merill Publishing.

Peters, T. (2023). The Voice of Public Theology. Adelaide: ATF.

Wolfe, S. (2023). The Case for Christian Nationalism. Moscow ID: Canon Press.