P { margin-bottom: 0.08in; } How does a person write from a spiritual center?

I can’t know for sure how other writers do it. I know which writers have sometimes moved my spirit in response to their words: Ally Lilly. Will Taber. Bright Crow. Peggy Senger Morrison. More Quaker writers than Pagans, I think, so perhaps there is something in how Quakers center themselves in Spirit in their work that feeds their words.

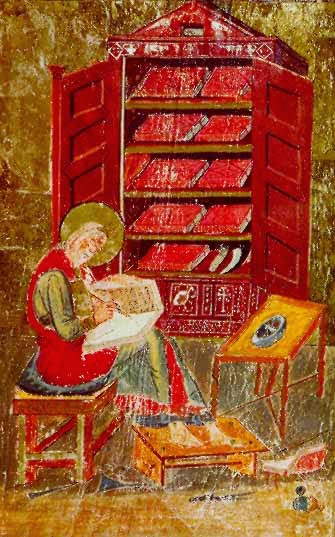

|

| Cassiodorus at the Vivarium |

Certainly, Quakers are told to “take heed of the promptings of love and truth in our hearts,” and to trust them as the leadings of Spirit. I know that the spiritual writing that moves me most seems to have been centered this way, and to comes out of direct, lived experience: “narrative theology,” as Peggy puts it.

So how’s it done?

While not every piece I write is this kind of writing, this is what I do, when I take on those pieces that I think of as spiritual writing–as “blogging in the spirit of worship,” as our strapline used to say.

First comes an initial impulse. This could be anything: the shape of a tree branch against the sky, a feeling of sadness as I pass the place a friend used to live. It’s usually something small: a single image or feeling that snags at my attention like a fingernail on a piece of silk. The writing takes shape around that first detail the way a pearl forms around a piece of grit.

That grit might be frustration, or fear, or grief—grief is good. Joy is better. A lot of my favorite writing comes from my efforts to fit joy into words.

That first snag does not come to me in abstractions. It comes as body memories: how I felt the day that Forest’s funeral was held. I think about it, and my eyes grow tight with the tears and glare of a morning forty years gone. Suddenly, I feel my spine pressing against a pew in an unfamiliar church, my teenaged self sitting bolt upright at the first funeral I ever attended.

Or I remember the sight of a bear cub moving across my garden. Or the sensuous pain of a lake on the first of June.

Then I go further in, fishing for sense memories to flesh out the moment. What was I wearing at the funeral? Was it my blue skirt, the one with the flowers? Did it feel as stiff as I did, in my strange, new emotions in a strange, adult world?

What did I do, when I saw the bear? Did I lean into my kitchen counter, straining to see him through the window as he moved? Did my breath fog the glass?

Next come words. What are the words for the feeling of my best, my least-familiar clothing? How do I describe the twitchy quality of that bear cub’s walk? Are there words for the smell of the lake in June? What life will fit in words?

Now I have it—that first paragraph, hopefully real and vivid. Maybe I even have a twist of unexpected words to catch hold of your mind as that first moment snagged at me. I have my “hook,” as writers say… except that’s wrong, isn’t it?

Because it’s not a hook, not really. It’s a touchstone, my touchstone, and it’s the moment when the Light broke in and made me notice something something new. It’s the moment the Truth grew out of, and I return to that moment again and again as I write. The rock of that sense-memory becomes the measure of my honesty: if I cannot trace my words back to that moment of lived truth, those words, I know, are not real, but “mere notions.”

Next I can wonder about meaning. Why has this image, this memory stayed with me? What is it trying to say within me? Did it open something in me that had been closed before? I let myself wonder.

This part of the writing comes the quickest—words pour onto the page. I begin to see cross-connections, interrelationships everywhere. I grow abstract, drunk with words… I pile them in drifts, higher, higher… stopping now and again to lean against my shovel. I break my paragraphs then.

The first stage of writing is sculpting with clay, adding it on and adding it on. I am impatient; I am flying; I am fire. And then comes the slow part, the taking away, cutting back and back and back to the image at the heart, the image that is true.

If the first stage of writing is sculpting in clay, now the words are marble. My love of the words has hardened, and must be carved away to find truth inside. (The cutting away is hard.)

At some point, though, the path becomes clear: a circle leading back again to my starting place, that moment of clarity that snagged my spirit to begin with. The shape of an ending suggests itself, and I sketch it out… but then I must read it back, maybe read it back out loud. Have I been precious? Did I force the ending into a shape, or did I step out of its way and let it shape itself?

Most of all, as I finish my work, I wonder, have I been faithful?

Quakers ask that question a lot, meaning, have we been faithful to God? When I am writing, though, that is not what I mean–not quite. I think what I am asking is, have I been faithful to this piece of writing, to this work that was put into my hand?

Of course, if I was responding to a leading, perhaps that comes down to the same thing: perhaps faithful to the work means faithfulness to Spirit. Of course, I have other questions as I finish–the ones that must be pushed away, at least until I’m done. Will other people like this? Is it good? Will anybody read it?

I push those questions aside, as best I can. And of course I revise–less than I should, probably, but more than I enjoy. And then… I publish it. I let it go.

Then, if I am lucky, I may hear back from someone: a reader, or maybe even more than one, who found my words really connecting to something inside of them–something that just needed the words to be out there. I read their comments, and my heart speeds up.

I feel joy, hearing their joy over words for a thing they needed said.