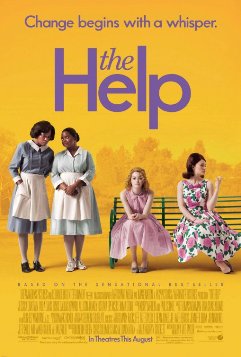

Last summer, I listened to the brilliant audiobook edition of The Help, and loved it so much that when I got to the end, I started again at the beginning.

So when I heard that a film version was in the works, I was terrified that it would be a disappointing botch-job of a book that moved me alternately to laughter and tears; stills and previews from the film made me fear that Hollywood would make the white woman (Skeeter, played by Emma Stone, no relation to me) the heroine in a story that, in so many ways, belongs to the black maids of Jackson, Mississippi. So often, film adaptations of books disappoint me by retaining a book’s external trappings and missing its spirit. (The Lord of the Rings, to me, does not capture the spirit of Tolkien’s books; by contrast, the Anne of Green Gables films change up L.M. Montgomery’s plot while retaining an essential Anne-ness.)

So when I heard that a film version was in the works, I was terrified that it would be a disappointing botch-job of a book that moved me alternately to laughter and tears; stills and previews from the film made me fear that Hollywood would make the white woman (Skeeter, played by Emma Stone, no relation to me) the heroine in a story that, in so many ways, belongs to the black maids of Jackson, Mississippi. So often, film adaptations of books disappoint me by retaining a book’s external trappings and missing its spirit. (The Lord of the Rings, to me, does not capture the spirit of Tolkien’s books; by contrast, the Anne of Green Gables films change up L.M. Montgomery’s plot while retaining an essential Anne-ness.)

I was not disappointed. The filmmakers did a beautiful job of condensing all that I loved about The Help–no short novel at 544 pages–into two and a half hours of hilarity, heartbreak, and human drama. To my mind, a big part of what makes a successful adaptation is the degree to which the filmmakers are willing to take license with the story in order to tell it in a way that is particular to the medium of film. So instead of lengthy scenes demonstrating Skeeter’s deep relationship with the maid who raised her, Constantine (a remarkable Cicely Tyson), the film gives us brief glimpses–Constantine braiding Skeeter’s hair on the steps of her rundown house, Constantine’s old fingers touching the marks on her doorframe that have measured Skeeter’s growth over the years–visual impressions that powerfully evoke an intimate and loving relationship.

So much of the book (and the film) uses basic bodily functions to communicate both the shared humanity of and gulf of separation between blacks and whites in 1960s Mississippi. References to taming hair and clothes to meet societal expectations are pervasive, as are motifs and themes related to toilet functions. Present (but in the book, less emphasized) is the motif of food and the theme of shared eating. I’m particularly tuned in to food issues, of course, but there was no missing the way in which the film capitalized on images of shared and segregated eating and drinking. The black maids must take care of their physical needs furtively and shamefully–sneaking a bite of deviled egg on the sly–all the while pampering the appetites of their white employers. Hilly Holbrook (a smoothly hateful Bryce Dallas Howard), will gorge herself on the food cooked by her maid, Minnie (Octavia Spencer, who voiced the same character on the audiobook), but expects her to use a designated outdoor one–even during a tornado. The film portrays the shame and belittlement of this segregation in cinematic shorthand.

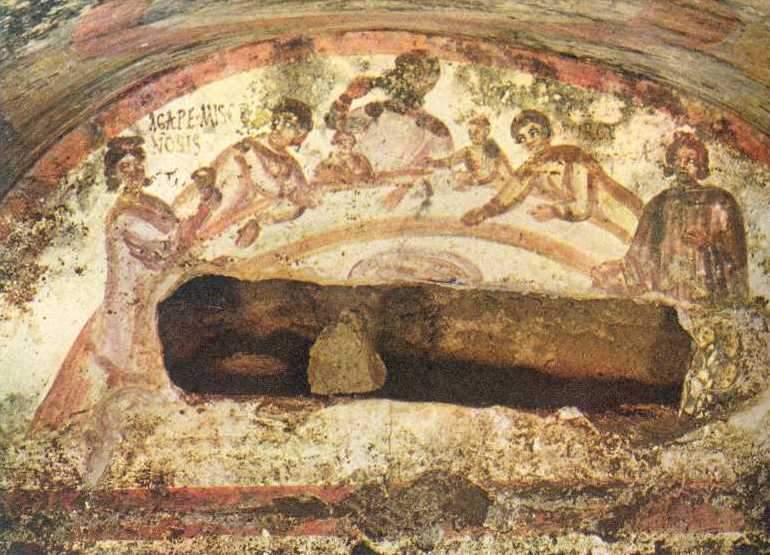

Where the film goes beyond the book (in its portrayal of food and eating), it aligns strikingly with my own understanding of a biblical theology of food. So much of food and eating, within the Bible, touches on issues of poverty, justice, community, and inclusion. In virtually every culture, sharing food non-ceremonially is an important indication of welcome and friendship; Jesus’ ministry emphasized the importance of eating with those who are different as a way of not just symbolizing—but, in fact actually practicing the kind of equality and unity that he proclaimed. Early Christian writers, too, claimed that sharing life, including meals, with persons of different backgrounds was a “proof” of true Christian faith. So when the outcast “white trash” Celia Foote (an effervescent Jessica Chastain) drinks a cold Coca-Cola with Minnie, it’s a foretaste not only of the meals she’ll later insist on sharing with (and then cooking for) Minnie, but a foretaste, too, of the coming healing, reconciliation, and deep friendship that forms between Minnie and Celia, and Skeeter, Minnie, and Aibileen (a luminous Viola Davis).

And that’s a foretaste, too, of the heavenly banquet.

Living the gospel acknowledges our shared humanity and need for reconciliation with God and with each other. When we sit to eat together, we acknowledge our physical needs and that shared humanity (we all eat; we all excrete) while tasting just a bit of God’s graciousness. The Help reminds me again just how countercultural that Supper of the Lamb really is, and inspires me to look for ways to taste the firstfruits of that meal in my own life, right now. And that, as the preacher in the film says, takes self-sacrifice and a willingness to hear one anothers stories. But it’s also the only way to true relationships and genuine joy.