David Brooks recently wrote an atrocious column in the New York Times that purports to look at the phenomenon of absentee fathers among poor American communities. He relies on research by Kathryn Edin and Timothy J. Nelson, who produced a book entitled Doing the Best I Can: Fatherhood in the Inner City.

My beef is not necessarily with Edin and Nelson or their book, but if the conclusions Brooks draws from it are what was intended by the authors, then it may require further scrutiny. Brooks draws a series of not just unfortunate, but incredibly harmful conclusions from the book and his prescriptions for solving the problem are even worse.

Brooks, and possibly Doing the Best, conceptualize fathers entirely in terms of their relationships with mothers: “The key weakness is not the father’s bond to the child; it’s the parents’ bond with each other.” Doing the Best finds that most fathers are excited about becoming parents, and that men are less likely than women to want to end unplanned pregnancies via abortion (of course they are, they’re not the ones going through pregnancy).

Here is how Brooks describes the typical deterioration of these relationships after the initial happiness of the child’s birth:

“The fathers often retain a traditional and idealistic ‘Leave It to Beaver’ view of marriage. They dream of the perfect soul mate. They know this woman isn’t it, so they are still looking.”

Brooks contrasts this patriarchal attitude with the supposedly-more-practical attitude of the women:

“Buried in the rigors of motherhood, the women, meanwhile, take a very practical view of what they need in a man: Will this guy provide the financial stability I need, and if not, can I trade up to someone who will?”

Then, of course, these immature, childlike men rebel against the practical nature of their child’s mother:

“The father begins to perceive the mother as bossy, just another authority figure to be skirted…By the time the child is 1, half these couples have split up, and many of the rest will part ways soon after.”

Finally, the cycle climaxes and then resets when the father moves on to do the same thing to another woman:

“The father redefines his role. He no longer aims to be the provider and caregiver, just the occasional ‘best friend’ who can drop by and provide a little love…He believes in fatherhood and tries it again with other women, with the same high hopes, but he’s really only taking care of the child he happens to be living with at any given moment. The rest are abandoned.”

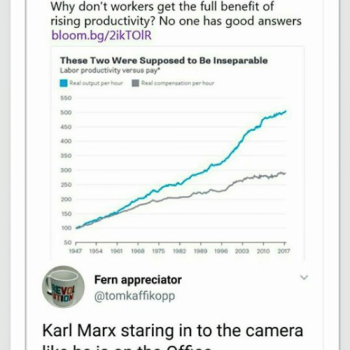

Absent in all of this, of course, is any discussion of economics: of the material realities that these people face on a day-to-day basis. Instead we are treated to the tired old racist tropes of the lazy, immature black father and the nagging, only-concerned-with-money asexual black single mother.

Brooks’s conclusion is that: “The good news…is that the so-called deadbeat dads want to succeed as fathers…but they’re stuck in a formless romantic anarchy. They need help finding the practical bridges to help them get where they want to go.” [emphasis added]

What are these practical bridges, and where are they supposed to lead?

“The stable two-parent family is what we want,” Brooks concludes. “A few economic support programs and a confident social script could make an enormous difference in getting us there.”

Instead of offering any examples of economic support programs, Brooks offers condescending advice such as “Find someone you love before you have intercourse” and “Create a couple’s budget to make sure you can afford this.” He also name-checks Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel as a “vocal leader in this cause,” failing to mention that Emanuel has been spearheading a racist policy of school closures, police violence, and segregation.

But it’s the first part that is most insidious. Brooks hearkens back to a romanticized, idealized vision of what marriage is or should be. But as Friedrich Engels taught us long ago, in The Origin of the Family, Private Property, and the State:

“That the mutual affection of the people concerned should be the one paramount reason for marriage, outweighing everything else, was and always had been absolutely unheard of in the practice of the ruling classes; that sort of thing only happened in romance – or among the oppressed classes, which did not count.”

Brooks’s idea of marriage is and was a patriarchal institution based on property rights. Engels explains:

“Monogamy was the first form of the family not founded on natural, but on economic conditions, viz.: the victory of private property over primitive and natural collectivism.”

Our idea of marriage developed alongside the concept of private property, and with it came patriarchy, misogyny, and the subjugation of women. Monogamy, as well as the “no-sex-until-marriage” attitude that Brooks espouses in his column, stem from the desire of men to ensure that their children are really theirs so that their property can never pass down into another’s family.

The supposed epidemic of “deadbeat dads” Brooks and others lament is the natural result of foisting bourgeoisie notions of marriage on oppressed people. People like Brooks (wealthy white people) do not stay married because they’re more romantic or because they love each other more, but because their marriages (whether they know it or not) are secured by vast quantities of wealth.

The “deadbeat dads” of America’s inner cities have no private property. They live in crippling poverty, and the notion that they should simply not have children if they can’t afford it borders on eugenics. None of them can afford it. This is why organizations like Black Lives Matter are opposed to the “traditional family;” it is an oppressive notion that has no place in their communities.

I don’t expect a dialectical materialist understanding of family relations from a neocon like David Brooks. What I do expect – what we all should expect – is a society that recognizes the material conditions faced by its citizens, and seeks to change those conditions when they create poverty and suffering.

Instead of treating monogamy as an end unto itself, we should seek to end the conditions that lead to families requiring two parents for children to receive all the opportunities they deserve. With financial pressures removed, fathers would be truly free to be there for their children.