This is the 100th anniversary of Eric Liddell winning the gold medal in the men’s 400m. He won it on July 11, 1924, but in this year‘s Olympics that event final is scheduled for August 7. And it is in Paris exactly as it was in 1924!

Today’s blog is the repost of one I first shared about Eric in 2018, with the addition of a few paragraphs and some tweaks here and there. If ever we were going to reshare a blog at a particular time, now is the perfect opportunity for this one.

One hundred years later, Eric’s example of wholehearted devotion to Christ is still inspiring countless readers. Even if you read this before, I hope you’ll be touched once again by his story. And I hope you’ll especially enjoy the story of Nanci and my meeting Margaret Holder on a trip to England in 1988, where to our great surprise and delight we discovered she was with Eric Liddell at an internment camp in the final five and a half years of his life, throughout her years as a teenage girl.

One of my favorite movies of all time is the 1981 Chariots of Fire. It’s the only reason many people are familiar with Eric Liddell, the “Flying Scotsman” who shocked the world by refusing to run the one hundred meters in the 1924 Paris Olympics.

Liddell first ran in the Scottish Championships as a 19-year-old in 1921. He won five times in a row in the 100 yards, 200, and 220. Later in 1924 and 1925, he also won the 440 yards, including his Olympic gold medal. At the AAA Championships, Liddell won the 100 and 200 in 1923 and the 440 in 1924.

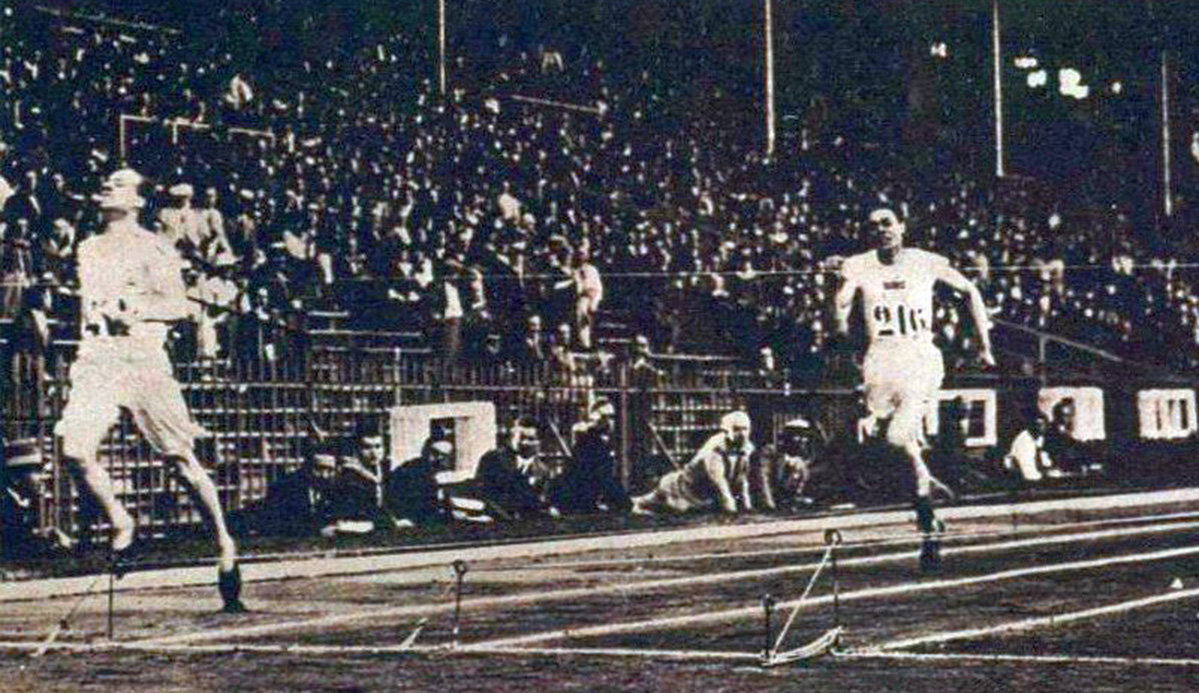

His time of 9.7 seconds for 100 yards in 1923 stood as a British record for 35 years. The 100m was his best race, one he was strongly favored to win at the Olympics, but also the one where his heat was scheduled on a Sunday, the Lord’s Day. He declined to run, giving up what was almost a certain gold medal. (As shown in the movie, in the absence of Liddell, Harold Abrahams won that race.) Eric then ran in the 400m instead and shocked the world by winning gold and breaking a world record, since he was a sprinter and that distance was considered too long a race for him. (In the black and white photo, that’s the real Eric Liddell in his gold medal winning 400m final at the Olympics.)

My favorite lines from the movie are when Eric’s character, played by actor Ian Charleson, says, “God…made me fast. And when I run, I feel his pleasure.” Though those lines were actually penned by screenwriter Colin Welland, I think the real Eric would have agreed with the sentiment. Those who knew him testified that his personal and moral convictions weren’t born of a cold, rigid religious piety, but of a warm, happy devotion to his Lord and Savior. Here’s that clip from the movie, with Eric talking to his sister Jenny.

I still remember sitting with Nanci in a large Portland theatre in 1981, smiling and crying through various parts of that unforgettable movie. Chariots of Fire ends with these brief words about Eric’s life after the Olympics: “Eric Liddell, missionary, died in occupied China at the end of World War II. All of Scotland mourned.”

A Tragic Ending?

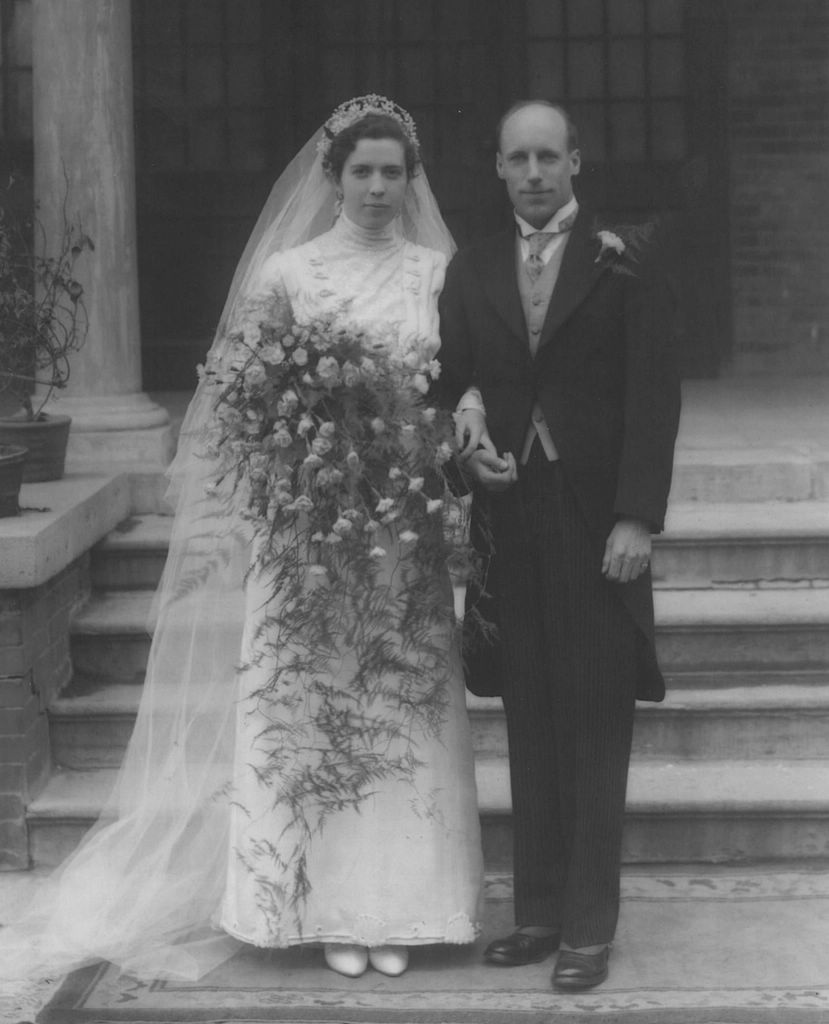

After the Olympics and his graduation, Eric returned as a missionary to China, where he had been born to missionary parents in 1902. When the Japanese occupation made life dangerous, he sent his pregnant wife, Florence, and their two daughters to Canada. Japanese invaders placed him in a squalid prison camp, without running water or working bathrooms. There, separated from his family, Eric lived several years before dying at age forty-three.

After the Olympics and his graduation, Eric returned as a missionary to China, where he had been born to missionary parents in 1902. When the Japanese occupation made life dangerous, he sent his pregnant wife, Florence, and their two daughters to Canada. Japanese invaders placed him in a squalid prison camp, without running water or working bathrooms. There, separated from his family, Eric lived several years before dying at age forty-three.

Upon learning of Eric’s death, it wasn’t just Scotland that mourned. All over the world people who had been inspired by him in the Olympics and in the Christian life joined the mourning.

On the surface, it all seems so tragic. Why did God withhold from this great man of faith a long life, years of fruitful service, the companionship of his wife, and the joy of raising those beloved children? It makes no sense.

And yet…

There is another way to look at the Eric Liddell story. Nanci and I discovered this firsthand when we spent an unforgettable day in England with Phil and Margaret Holder, in May of 1988. We knew almost nothing about the Holders except that Phil was a pastor. Some missionary friends we were visiting in England took us to their home in Reading.

Margaret was born in China to missionary parents with China Inland Mission, founded in 1865 by Hudson Taylor. In 1939, when Japan took control of eastern China, thirteen-year-old Margaret was imprisoned by the Japanese in Weihsien Internment Camp, where many foreigners in Beijing were sent to. There she remained, separated from her parents, for six years. (Can you imagine this not only from a young girl’s perspective but that of her parents, last being with their daughter at age 13 and not seeing her again until she was 19?)

Margaret told stories to Nanci and me about a godly man she called “Uncle Eric.” She said he tutored her and was deeply loved by all the children in the camp. She looked at us and asked, “Do you know who I’m talking about? Uncle Eric’s name was Eric Liddell.”

I recall like it was yesterday how stunned we were (gobsmacked as they say in England where we were with the Holders) because Chariots of Fire told one of our favorite stories of all time. It was released in the fall of 1981 when Karina was two years old and Angie was only four months old. Nanci and I had watched it several times in the seven years since it was released and had countless conversations about it with our closest friends. Now here we were learning firsthand information about one of our heroes!

Uncle Eric’s Influence

Margaret shared with us many great stories that day, one of which illustrated this man’s Christlike character. In the camp, the children played basketball, rounders, and hockey, and Eric Liddell was their referee. Not surprisingly, he refused to referee on Sundays. But in his absence, the children fought. Liddell struggled over this. He believed he shouldn’t stop the children from playing because they needed the diversion.

Margaret shared with us many great stories that day, one of which illustrated this man’s Christlike character. In the camp, the children played basketball, rounders, and hockey, and Eric Liddell was their referee. Not surprisingly, he refused to referee on Sundays. But in his absence, the children fought. Liddell struggled over this. He believed he shouldn’t stop the children from playing because they needed the diversion.

Finally, Liddell decided to referee on Sundays. This made a deep impression on Margaret—she saw that the athlete world famous for sacrificing success for principle was not a legalist. When it came to his own glory, Liddell would surrender it all rather than run on Sunday. But when it came to the good of children in a prison camp, he would referee on Sunday.

Liddell would sacrifice a gold medal for himself (though he ultimately won the gold in a different race) in the name of truth, but would bend over backward for others in the name of grace.

A Godly Example

Mary Taylor Previte, imprisoned at Weihsein as a child, described Eric as “Jesus in running shoes.” Dr. David J. Michell, who was also one of the children at the camp, wrote how besides sports, Eric Liddell taught the children his favorite hymn:

By still, my soul, the Lord is on thy side;

Bear patiently the cross of grief or pain;

Leave to thy God to order and provide;

In every change He faithful will remain

Be still, my soul, thy best, thy heavenly Friend

Through thorny ways leads to a joyful end.

Dr. Michell also wrote:

Eric Liddell often spoke to us on I Corinthians 13 and Matthew 5. These passages from the New Testament clearly portray the secret of his selfless and humble life. Only on rare occasions when requested would he speak of his refusal to run on the Sunday and his Olympic record.

…Not only did Eric Liddell organise sports and recreation, through his time in internment camp he helped many people through teaching and tutoring. He gave special care to the older people, the weak, and the ill, to whom the conditions in camp were very trying. He was always involved in the Christian meetings which were a part of camp life. Despite the squalor of the open cesspools, rats, flies and disease in the crowded camp, life took on a very normal routine, though without the faithful and cheerful support of Eric Liddell, many people would never have been able to manage.

…None of us will ever forget this man who was totally committed to putting God first, a man whose humble life combined muscular Christianity with radiant godliness.

What was his secret? He unreservedly committed his life to Jesus Christ as his Saviour and Lord. That friendship meant everything to him. By the flickering light of a peanut-oil lamp early each morning he and a roommate in the men’s cramped dormitory studied the Bible and talked with God for an hour every day.

Marcy Ditmanson, a Lutheran missionary imprisoned with Eric, shared his recollections:

Eric spoke with a charming Scottish brogue, and more than anyone I had ever known, typified the joyful Christian life. He had a marvelous sense of humor, was full of laughter and practical jokes, but always in good taste. His voice was nothing special, but how he loved to sing, particularly the grand old hymns of the faith. Two of his favorites were “God Who Touches Earth with Beauty” and “There’s a Wideness in God’s Mercy.” He was no great orator by any means but he had a way of riveting his listeners with those marvelous, clear blue eyes of his. Yes, that’s what I remember most about him as he spoke―those wonderful eyes and how they would twinkle.

Full Surrender

Though he had become an “uncle” and father figure to numerous children, Eric Liddell never saw his own wife and daughters in this world again. After writing a letter to Florence from his bed in the infirmary, he said to his friend and colleague “It’s full surrender” and slipped into a coma. Suffering with a brain tumor, he died in 1945. And while all Scotland mourned, all in Heaven who had cheered Eric on as a servant of Jesus gave him a rich welcome.

Through fresh tears that unforgettable day in their living room, Margaret Holder told us, “It was a cold February day when Uncle Eric died.” No one in the world mourned like those in that camp. When five months later the children were rescued by American paratroopers and reunited with their families, many of their stories were about Uncle Eric. Liddell’s imprisonment broke the hearts of his family. But for years—nearly to the war’s end—God used him as a lifeline to hundreds of children, including Margaret Holder.

Viewed from that perspective, the apparent tragedy of Liddell’s presence in that camp makes more sense, doesn’t it? I’m convinced Liddell and his family would tell us—and one day will tell us—that the sufferings of that time are not worthy to be compared with the glory they now know…and will forever know. A glory far greater than the suffering which achieved it.

Viewed from that perspective, the apparent tragedy of Liddell’s presence in that camp makes more sense, doesn’t it? I’m convinced Liddell and his family would tell us—and one day will tell us—that the sufferings of that time are not worthy to be compared with the glory they now know…and will forever know. A glory far greater than the suffering which achieved it.

In an interview with Liddell’s youngest daughter, Maureen, who he never met, she shared this after visiting the granite monument in China dedicated to her father’s memory: “I felt so close to him and, more than ever, I realized what his life had been for. It all made sense. What happened allowed him to touch so many lives as a consequence.”

Her sister Patricia agreed:

The number of people he’s influenced … well, things seem to add up, don’t they? You only appreciate it when you look at each stage of his life and make the connections between them. …I used to ask myself: How would things have turned out if the three of us and our mother had been in the camp with him? Then I understood my father would have spent less time with the other youngsters, which would have deprived them of so much. That didn’t seem fair to them. He was needed there. The stories we heard after his death prove that.

If we can look at Eric and his family’s tragedy, and others’ tragedies, and see some divine purpose in them, it can help us believe that there is purpose in our own tragedies too. It can help us believe the blood-bought promise of God: “all things work together for the good of those who love God, who are called according to his purpose” (Romans 8:28, CSB).

A Joyful End

Though years ago I had been deeply touched by Liddell’s story watching Chariots of Fire, it was what Margaret Holder told us that day that really made me look forward to meeting in Heaven this man whose Olympic gold medal was nothing compared to his humble service for Christ.

Dr. Norman Cliff, who was imprisoned with Eric, recalled this:

Eric Liddell would say, “When you speak of me, give the glory to my master, Jesus Christ.” He would not want us to think solely of him. He would want us to see the Christ whom he served.

I’m counting on Eric, in his resurrection body on the New Earth, being able to move slowly enough for me, in my resurrection body, to run alongside him. Together, we’ll worship our Lord and Savior, the One to whom all glory and praise is due.

I’m counting on Eric, in his resurrection body on the New Earth, being able to move slowly enough for me, in my resurrection body, to run alongside him. Together, we’ll worship our Lord and Savior, the One to whom all glory and praise is due.

You might enjoy this last clip of Eric racing in Chariots of Fire. He was known for looking face up to breathe deeply, and sometimes flailing his arms. His reckless abandon and face skyward beautifully symbolize how he set his eyes on the risen Christ in Heaven.

If you wish to know more, here’s an article on Eric’s life, and here’s another I read and loved, about his life after the Olympics. And finally, here’s a great article about Eric from the C. S. Lewis Institute.

To hear a short but heart-touching story about the rescue of Margaret Holder and the other children from that prison camp in China, check out our next blog.

Top photo: Le Miroir des sports, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons