“Religion is the vision of something which is real and yet waiting to be realized . . . .”

—Alfred North Whitehead, Science and the Modern World, 275

There are dangers of speaking of the dead. Derrida warned against the possibility of using another’s death, even unintentionally, for one’s own end, or “to draw from the dead a supplementary force to be turned against the living . . . ” (2001, 51). The risk is double here in that I did not personally know those who died—in this case Michael (MJ) Sharpe and Zaida Catalan, both members of the UN’s Group of Experts, along with their interpreter Betu Tshintela—whose bodies were found in late March in the same region of the Congo where they had been investigating human rights violations.

There are also dangers, of a much different kind, when going into armed conflict zones, something that Michael Sharpe had been doing much of his adult life, having spent three previous years in Congo with Mennonite Central Committee, mediating between armed factions to end ongoing violence in the region (Campbell 2017). It was Michael’s skill in listening and building trust with rebel leaders—leaders who certainly had participated in egregious violence—that led the UN to invite him to the Group of Experts, and to head the investigative council for Congolese conflicts (Bearak 2017).

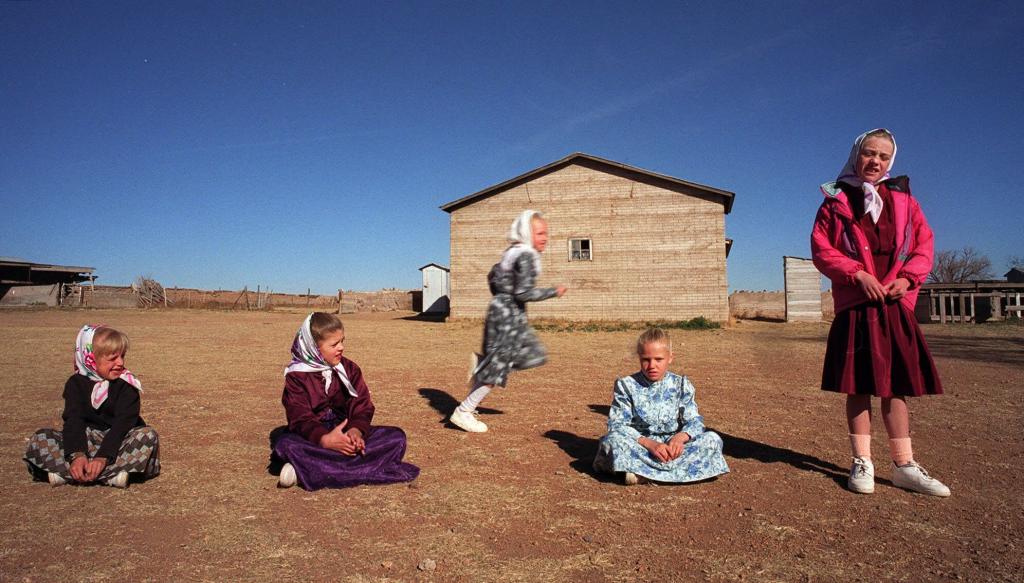

Reflecting on the deaths of Sharpe and Catalan through the lens of the Anabaptist-Mennonite community, to which Michael belonged, has reminded me again of the possible costs of peacemaking that was instilled in me repeatedly throughout my learning alongside Mennonites during my undergrad and graduate school. Though I was not raised Mennonite—and had actually dropped out of college two times previously—I was intrigued by a community rooted in a resistance to state-supported violence. Anabaptist-Mennonites, along with Brethren, and Quakers are considered “historic peace churches,” referring to their shared commitment that the New Testament forbids Christian participation in war and violence. It was not an idea I knew much about, and it seemed then, as now, such a marginalized view—almost totally overshadowed by Augustine’s legacy of “just war”[i] and the gradual conflation of Christianity and militarism that still characterizes U.S. policy and rhetoric. I wanted to learn more, a learning that transformed, and continues to challenge my own life and thought-worlds.

Many people think of pacifism as utterly passive, or as a form of utter nonresistance. In this light, conscientious objection to or peacemaking in the face of state violence appears a form of principled, and usually useless, naiveté. That is not an accurate notion of the risks of nonviolent resistance, active peacemaking, or the mediating tasks of conflict resolution.

Shortly after Michael and Zaida went missing on March 12, Michael’s father John, a professor at Hesston College (an institution with Anabaptist roots) stated to Mennonite World Review, “I have said on more than one occasion that we peacemakers should be willing to risk our lives as those who join the military do. Now it’s no longer theory” (McMaster 2017). And in another interview with the Wichita Eagle, John, and his wife Michele Miller Sharpe, asserted that “MJ is committed to finding nonviolent ways to resolve conflict. He is aware that 20 years of violence in eastern Congo has solved nothing – he was working to find a better way” (McMaster 2017).

These thoughts brought to mind a recent conversation with a mentor who reminded me of Walter Wink’s helpful interpretation of Matthew 5:38-39, when Jesus says “You have heard that it was said, ‘Eye for eye, and tooth for tooth.’ But I tell you, do not resist an evil person. If anyone slaps you on the right cheek, turn to them the other cheek also.”

At first glance this phrase looks like pure passivity, but Wink pushes past that view, asking us to consider the political-physiology of this act (1999, 101-2). If we assume that most people are right-handed, the only way that one can face you and slap you on the right cheek is by doing so with the back of their right hand (go ahead; take a second to picture that). This kind of backhand slap, according to Wink’s historical analysis, was delivered by one in high power to one with little power. For the one slapped to strike back would have bleak, even fatal, consequences. So why suggest to offer the other cheek also? And in the next verse, to give your cloak, as well, to one who want to sue you for your tunic (5:40)? And in the next verse, to go a second mile when one forces you against your will to carry their belonging for the first (5:41)?

Such actions, suggests Wink, are not a recipe for willing victimization as expressed in the facile quips to “turn the other cheek” or “go the extra mile,” as if to forgive and forget, or even to invite more abuse.

These passages reveal strategies of resistance in light of the common practice of retributive justice that prefaces these seemingly masochistic commands: “You have heard that it was said, ‘Eye for eye, and tooth for tooth’” (5:38). Yet what access to retributive justice does an outcast have to one in political power? Jesus was certainly well acquainted in his time of justified rebellions squashed by brutal state power—and such has been the drama too often of underdogs against oppressors throughout historic memory, into our present news cycle.

Though offering the other cheek cannot correct the power imbalance between the violator and violated, in a situation of great inequity it can restore agency to the one violated. Offering the other cheek to a perpetrator provides a chance for that perpetrator to think about their violence, and the shared humanity, or common life force, between themselves and their victim, as a way to disrupt a perpetrator’s conditioned view, their privilege, and possibly make a step toward restoring that person’s humanity.

Violence toward bodies[ii] requires a one-dimensionalizing of another. The Jains of India, characterized by a thorough-going commitment of monastic nonviolence toward all life forms (and to a lesser degree by the Jain lay community), recognized the connection between one-sided affirmation and justifications of violence in their ancient doctrine of anekāntavāda, or non-one-sided perspective (Long 2009, 141). The best views, Jain philosophers asserted, would investigate how multiple, even seemingly contradictory views, might have some truth from a certain perspective. Further, violence requires the denial of another’s claim upon us. Violence requires an erasure of our common bond of life. What modes of resistance can interrupt these habits?

For Michael Sharpe, that mode of resistance often took the form of listening. “You can always listen,” he said in a 2015 NPR interview while working with the Congolese Protestant Council of Churches in their Peace and Reconciliation Program. “You can always listen to people who want a chance to talk about how they see the world” (Campbell 2017).

On one hand listening to militia leaders responsible for grotesque violence may feel intolerable, even immoral. We need not look farther than our own political fractures at present to know how difficult listening is, much less understanding, even when armed conflict is not at stake. In a recent reflection on Sharpe’s death, Joe Liechty—a professor at Goshen College and a former mediator amid Northern Ireland’s sectarian conflicts—wrote a reflection on Sharpe’s death. Liechty is no apologist for Mennonites, who have their own share of conflict, but “ . . . at our best,” he writes, “we do what Michael Sharpe did” (2017). And to listen well, a simple “principle [that] applies in every kind of conflict, from the interpersonal to the international” is part of that work (Liechty 2017). “So why listen?” he asks, and a selection of his responses follow:

- Because you’ve just got to understand, you ache to understand, and listening is the beginning of insight and maybe wisdom.

- Because to listen is to offer a gift that can sometimes spark and nurture trust, and no real peace is possible without some level of trust.

- Because listening well may allow you to be heard.

- Because listening is an almost secret form of power, hiding in plain sight, especially available to the less powerful . . .

- Because to listen is to honor and respect, potentially opening new possibilities for those who have been shamed, dishonored, disrespected.

- Because to listen is to invite a relationship, and the magic of relationships can shift what is blocked, animate what has seemed lifeless. (Liechty 2017)

We might ask, as I felt I often did while studying with Mennonites, “But what if someone else has done violence first?” How do we listen then, or offer the proverbial other cheek? This is an intractable question. It is question that may be born of injustice, unfairness, fury, grief, violation, or the desire for any solution that might mend the broken scales that measure out basic dignities and respect for another’s existence.

I am not wise enough to know the answer, but I do want to keep the question alive.

Whatever the motivation for violence, and even perhaps especially when we think violence is justified, it still demands all of the above requirements of one-dimensionalizing, denying another’s claim upon us, and an erasure of common bond. A victim can quickly become the perpetrator whose own humanity has gone missing.

I do not know how to solve that quandary, only that it is often true. That we might train up a force of strategic peacemakers, conflict mediators, skilled and unarmed resisters, those willing to step between opposing sides and strive to listen to them all in some respect, is an ideal, I believe, worth striving for.

Certain pragmatists and critics will say (and I include myself here, at times), “But what about _________? ” You can fill in that blank here with terms such as “true evil” or “state violence” or “if someone hurt your child” or “if you could stop someone killing a thousand others” or “if it was Hitler” or “if someone has no humanity left to restore?”[iii] These realities pain me—not least of which because they are genuine moral dilemmas, and I am not foolish to think some ideal of nonviolence makes them less so. My own capacity to feel rage, and desire for self-preservation, prevents me any pure perspective, and I find that most who pursue the goal of nonviolent resistance grapple continuously within these constraints.

Yet in daily practice, I think we must imagine the character of a world that we want to experience, and risk ourselves toward that vision within our own conflicts—whether emotional injuries, social media battles, racial fractures, harmful ideologies, destructive political policies, criminal violations, callousness, and otherwise; “courageous, but not reckless,” as one of Sharpe’s colleagues in the Congo described him (Bearak 2017). We must put energy, creativity, and resources into strategies meant to restore the humanity of perpetrators—whomever those may be to us here and now—and even to free them from the enslavement of their privilege or homogeneity, while maintaining our own humanity.

In walking that blurred line, and without the assurance of being right, I honor the life and death of MJ Sharpe—and all who put their bodies between the barbs of conflict, those who strive to listen—for bearing forth that foolish courage toward visions still waiting to be realized.

Brianne Donaldson is a public ethicist exploring the intersection of Indian and western thought, critical animal studies, and religion and science. The goal of this work is to rethink relations between plants, animals, and people, and to undermine systematic violence toward excluded populations. She is the author of Creaturely Cosmologies: Why Metaphysics Matters for Animal and Planetary Liberation (Lexington Books 2015), and two edited collections: Beyond the Bifurcation of Nature: A Common World for Animals and the Environment (Cambridge Scholars Publishing 2014), The Future of Meat Without Animals (Rowman and Littlefield International, 2016). She currently holds the Bhagwaan Mahavir/Chao Family Foundation Fellowship in Jain Studies at Rice University in Houston, Texas. www.briannedonaldson.co

References and notes:

Bearak, Max. 2017. ‘Courageous but not reckless’: The tragedy of an American U.N. worker slain in Congo. The Washington Post. March 29. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/worldviews/wp/2017/03/29/courageous-but-not-reckless-the-tragedy-of-an-american-u-n-worker-slain-in-congo/?utm_term=.1c1354a54a5c

Campbell, Barbara. 2017. U.N. Human Rights Investigators Killed In Democratic Republic Of The Congo. National Public Radio. March 28. http://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2017/03/28/521861266/u-n-human-rights-investigators-killed-in-democratic-republic-of-the-congo

Derrida, Jacques. 2001. The Work of Mourning. Ed. Pascale-Ane Brault and Michael Nass. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Donaldson, Brianne. 2015. Creaturely Cosmologies: Why Metaphysics Matters for Animal and Planetary Liberation. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

Liechty, Joseph. 2017. Personal Facebook post. March 30.

Long, Jeffery. 2009. Jainism: An Introduction. New York: I. B. Tauris.

McMaster, Rachel. 2017. Body found in Democratic Republic of Congo confirmed as son of instructor. Hesston College. March 28. Viewed April 1, 2017 at http://www.hesston.edu/2017/03/body-found-democratic-republic-congo-confirmed-son-instructor/

Wink, Walter. 1999. The Powers That Be: Theology For a New Millennium. New York: Doubleday.

[i] Alternate just war theories also exist—which are distinct and contextual—such as the Islamic tradition of just war to set rules and limits on conflicts, rooted in the Qur’an.

[ii] Alternative arguments must be made regarding violence toward non-living property; direct action movements debate the efficacy of targeted destruction of property to prevent the violation of living beings. This has been a strategy of Earth Liberation Front and Animal Liberation Front, both considered domestic terrorist organizations. I have written about this in Donaldson 2015, Introduction.

[iii] Mennonite author John Howard Yoder, a complex and contradictory figure in his own right, wrote a short book specifically addressing questions such as this, as well as alternative responses to violence called What Would You Do? (Herald Press; Revised edition 1992).