By Robert Orlando

Communism or Christianity? Given their origins, we might quickly conclude that these worldviews are irreconcilable, and they might be. Yet, they have one thing in common, which might be the reason for the hostility we see on the streets.

If there is no resolve, we will likely face another civil war. Below is an attempt to explore the contours of these systems, where they converge and diverge, and ask whether the U.S. can survive without reconciliation?

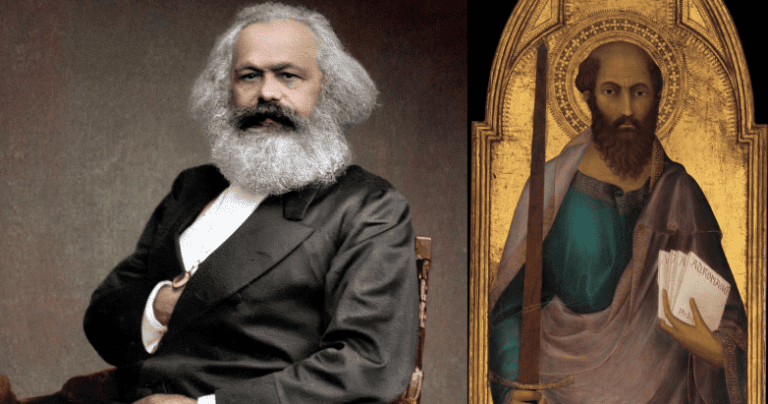

For both the Apostle Paul and Karl Marx, the ideal state (without struggle) of human relations is the absence of distinctions between class, gender, and race/ethnicity. The Apostle Paul, with the coming Kingdom “in Christ,” wrote, “gone is the distinction between Jew and Greek, slave and freeman, male and female—you are all one in Christ Jesus” (Galatians 3:28). In his Communist Manifesto, Karl Marx would insist on the erasure of distinctions of marriage, or ethnicity/nationhood, to prepare the way for the revolution, his Communist Kingdom.

As one in a line of rabbis, Marx would have also known the Jewish prayer (siddur) states, “Blessed are you O God, King of the Universe, Who has not made me a Gentile, a slave, or woman.” Marx envisioned a society in which neither Jew nor Christian would exist. Paul never ceased being a Jew, but the Kingdom’s arrival meant the Jew-Gentile distinctions would “pass away,” and a new epoch began with Christ. As the Kingdom tarries two millennia, and with a resurgence of Marxism, how shall we view these distinctions? How should we redefine Paul’s living “in Christ” in light of an encroaching world?

Paul, as did others, expected Christ’s immediate return, which was cause for his first letter. As scholars might vary on the symbolism vs. literalism of his words (1 Thessalonians 4:13-5:11, Romans 13:11), Paul, with the Messiah’s arrival, was seeing through a Jewish Apocalyptic lens. Zechariah prophesied that God’s mercy would pour out on all nations in the final days, and the Gentiles, in gratitude, would offer gifts to the Temple. The very reason for Paul’s collection for Jerusalem and his final journey (Romans 15:28-31).

Before he arrived in the Holy Land in 58 A.D. on his final mission, the Apostle urged the Gentile majority not to forget they had been “grafted” into Israel’s tree (Romans 11:17). They were privileged to have joined a Messianic age without ethnic distinction, which would have been a direct threat (Acts 21:17-26) to the Jewish believers who had maintained the unique role of the Jews as the chosen people. Marx was dismissive of his faith and religious distinctions and spoke solely in political terms of equal Jewish citizenry in Prussia.

When Paul returned to Jerusalem with his collection accompanied by Gentiles as a symbol of the united people, he referred to the movement as “in Christ.” In this case, he was a revolutionary. A mob attempted to kill him (Acts 21:27–36). The Temple authorities rejected an open display of Jews and Gentiles in eco-politico unity. Paul, “a friend of the Romans,” had offered them a “revolution” in Christ. Marx had a secular version of the same effort, but in his case, eliminating distinction.

One could argue that there would be a violent climactic ending in both cases, whether the 19th century or the 1st century. Jesus himself said that he had “not come to bring peace, but a sword” (Matthew 10:34) – perhaps as the result of his message. Such a gap of two thousand years begs a serious question: How shall we then live in the interim?

Is the reconciliation of man and woman, Jew and Greek, or the classes, only possible with the new Kingdom of God? Or is Marx right that only political revolt will bring a system of justice for all?

Our modern defense against groupthink does not guarantee moral progress, so there must be a collective consideration of individual self-identity. But to trust politicians as guides for social justice from a secular state, in this writer’s opinion, is a madman’s errand.

Paul’s promise “in Christ” was not a political utopia, but a cosmic redemptive hope that “with unveiled face, beholding the glory of the Lord, are being transformed into the same image from one degree of glory to another” (2 Corinthians 3:18). Paul refers to a daily transformation of the heart, body, and mind, with a complete redemption determined by God.

In other words, we perfect this world through our care of our brothers and sisters, with faith and love, not with a benevolent dictator or enlightened ruling class. Still, in our self-identity journey, like Israel’s (then and now), we must define ourselves as a nation, as an American people.

Unlike Marx, Paul did not want to destroy the Jewish legacy in Jerusalem but perfect its role with unity of purpose in Christ, which became the Judean-Christian history of the West. Jerusalem would maintain its national identity within the Roman Empire but greet the distinctions with a new empathy.

As global forces encroach upon us via the digital highway with their high-tech gospel, we face the same challenge that Paul faced in the Roman Empire. Are we Americans or the whole world? Do we belong to a worldwide revolution, or are we still that chosen entity Reagan called a city on the hill? Would the latter include human boundaries like family or culture, as well as national boundaries?

As Marx would have suggested, our mission is not to abolish our distinctions and rip them from their Western roots but to maintain a boundary between sacred and profane. Jesus said, “render to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s and to God the things that are God’s” (Mark 12:17).

The Apostle Paul would want us to tarry with patience, and Marx would wish for a revolution now. We have seen how Marx’s ideas have worked out in the figures of Stalin and Mao, and we know how the Romans burned down Jerusalem in 70 A.D. and sent the Jews into exile until 1948.

The question remains: where should Americans find their Kingdom?