I got to Atlanta last night. This morning I picked up my tote bag which included my name tag holder. Nearby, the book exhibit was soon to open, and so I saw and chatted briefly with several people I know who were waiting there.

There is really impressive attendance at the first session I attended, part of the John, Jesus, and History program unit, which I used to be more involved with in the past than I have been lately. But as I round up the Mandaean Book of John translation and commentary project, and look ahead to the next book I want to write post-sabbatical, about the Mandaeans, Christian Origins, and the New Testament, I have been turning my attention back to this older area of interest of mine. The session today also includes one paper in particular which relates directly to the Enoch Seminar meeting in Italy next summer, Jewish Messianism and the Gospel of John. The overarching theme of the program unit of late is whether the distinctive developments in John – Jesus as Word-made-flesh, for instance – renders other terms, such as rabbi and prophet, no longer of interest.

The first paper was by Graham Twelftree, looking at healings in the Gopel of John, asking why certain things are left out, and why what is included was included. He notes that the miracles included in John are all spectacular. He suggests that John focuses on Jesus’ identity, but that acting “as God,” a major thing Jesus does is heal people. But the healings are unambiguous. This is offered as an explanation for the removal of exorcisms. Exorcisms in that time were commonplace, and failed in any way to single Jesus out as unique. Twelftree also looked at the terms used, “signs” being significant because its use in the LXX focus on divine action, often action which authorizes God’s agent. The works are never said to be Jesus’, but always the Father’s. Twelftree then went on to survey each healing in turn. References to the sabbath are consistently connected with Jesus’ healing activity – and look like insertions by the evangelist into the narrative rather than something that was part of the tradition he inherited. And so far from being a past matter, healing on the sabbath seems to have been an ongoing concern for the Johannine church and a reason for which they were persecuted. The making of mud with spittle is something common among healers, and so this might seem to undermine the suggestion that John is trying to focus only on healings and actions that make Jesus seem unique. But then again, healing a man born blind by any means was still distinctive. In the raising of Lazarus, the phrase “the Messiah, the Son of God” is used, a phrase found elsewhere only in the purpose statement towards the end of the Gospel. Twelftree suggested that this indicates that it was in healings par excellence that one recognized who Jesus is. The passion and resurrection are echoed in the healings.

The second paper was by Tom Thatcher and focused on Jesus as controversialist. He began by noting that, despite having been involved in setting up the program unit some 14 years ago, he had not presented a paper in a session! The paper focused on two questions: did Jesus act on the sabbath in ways that he intended to generate controversy, and by what method can we tell? Thatcher’s approach is a media-critical one. He is looking for verisimilitude, a match with the “outside world,” the real world of Jesus, an approach that not everyone considers the way to get at memories of historical events. John 5-10 is focused on sabbath healing controversy, and in chapters 5 and 9 he heals in ways that ask or even require those healed to violate the sabbath. Thatcher views Jesus as setting his sights on the brokers of the great tradition. He says John remembers Jesus doing these things as an act of protest. But now comes the question of whether all of this fits what we would expect to find in the actual career of Jesus, and Thatcher skirted the question almost entirely of how we might know. But he did point out that memory does not work in such a way that we could pull out one thread and analyze is as authentic or inauthentic in isolation from the whole. The argument in John 7 boils down to this: only God could heal someone lame for so many years, so God must think that healing on the sabbath is OK, and so why are the powerful 1% trying to prevent it? Thatcher speaks with the cadences of a preacher. He suggests that prophets don’t engage in exegetical debates, but throw down the gauntlet. The powerful tried in the story to use literacy and education as a way of brokering who deserved to be listened to. Thatcher says that when he looks at the structures of power and the importance of sabbath in the social world of Jesus in Roman Palestine, they match what he sees in John. After the paper, there was some interesting discussion with questions reflecting more classic historical-critical methods. In the process, Thatcher emphasized that he sees chapters 5-10 as a single unit, which I think makes good sense. It is an extended controversy about healing on the sabbath – arguably with chapter 6 inserted into the midst of it, although I am not sure whether Thatcher would agree.

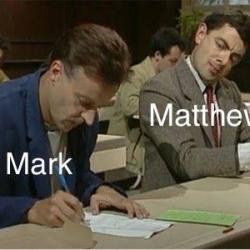

The third paper was by Matthew Novensen, about Jesus as Messiah. He started by quoting Bultmann, who said that in John, one feels that one has been transported away from Jewish messianism to the world of the Corpus Hermeticum. On the one hand, John himself introduces key Jewish ideas, while on the other, John’s own view does not look exactly like any of those. Novensen mentioned the Samaritan idea of the Taheb (“he who returns” or “he who restores”). Hugo Odeberg once suggested that John actually wrote “Taheb” and scribes dropped it, but Novensen considers it more likely that John has simply substituted – whether deliberately or through confusion – “Messiah.” The paper also discussed whether the complaint that Jesus is not a Davidide from Bethlehem is an example of irony, since it would involve far greater subtlety than other instances. John is unconcerned with Jesus’ family tree, rather than directly opposing the idea that Jesus was of Davidic descent and/or from Bethlehem. Novensen also mentioned that, while some specifics of Martyn’s thesis have not stood the test of time (e.g. about the birkat ha-minim), his connection of the Gospel with a context of Jewish controversy in later Christian experience continues to command widespread, although not universal, assent. In conclusion, Novensen noted that the focus on “Messiah” in John has in the past aimed either to argue for or against the historical veracity of John in relation to Jesus’ first century context, or to identify distinct literary layers. I got a mention alongside Wayne Meeks as representative of a view of John as drawing on an array of strands which are woven together in a distinctive way that is not simply “historical” or “unhistorical.” Novensen turns then to the Gospel of Philip, with its discussion of the meaning of “Jesus Nazarene Christ.” What does it tell us that this third cenury Eastern Valentinian text reinterprets rather than abandoning older terminology? Novensen said that John had bigger fish to fry, and I could not help but wonder whether he had John 21 in mind. John has a conservative streak, as well as being an innovator. In the question time, Novensen mentioned the different messianic ideas, including the possibility to be Davidesque without being a Davidide, such as when Davidic messianic ideas were applied to Bar Kochba, without it being claimed that he was descended from David.

The last paper was by Alicia Myers, focused on sonship as going beyond metaphorical usage to a unique ontological claim. Rather than spend a lot of time discussing the nature of metaphor, Myers builds on Akela’s work on the Father-Son language in John, also making positive reference to Marianne Meye Thompson. Other scholars, including Reinhardtz, have related ancient ideas of conception, including in particular Aristotle, to the Johannine prologue. It was the male that was thought to provide the key contribution, and so God generates his Son with no need to make reference to his mother. A handout provided a chart highlighting terminological connections between the prologue and chapters 3 and 5 in the Gospel of John. Some words do not occur in the intervening chapters. Myers notes Jo-Ann Brandt’s cautionary remarks that looking at vocabulary along can be misleading, since an author may vary words for stylistic reasons rather than to make some point, theological or otherwise. I would have liked to hear more about Myers’ understanding of the charge in 5:18, which becomes a sticking point from that point on. But she did note Brandt’s and also Lori Baron’s work on the topic, understanding Jesus to be including himself in the Shema, and thus the attacks on his were motivated not by a metaphorical relationship that Jesus and others might be said to have towards God as Father, but a unique claim. It is not a royal claim but an ontological one that is at the basis of the depiction of Jesus as life-giver.