I was really struck by a post on the blog Only a Game, coming as it did right when I was preparing to speak at Gen Con about gamification and the arts in higher education together with a couple of other Butler University colleagues. In it Chris Bateman writes:

If a game console is a device designed for the express purpose of executing arbitrary programmatic systems for entertainment, then the deck of cards was the world’s first game console. All previous games except dice had components specific to their design, but this was not the case for the first cards (quite possibly Chinese ‘money cards’, although the history of the deck of cards is rather hard to trace owing to the poor survivability of actual cards). By creating a set of components that were coded into both numerical values and suits (usually four), human-deck cyborgs had a means to create myriad different games – and have indeed exactly this over the millennia that followed.

Now the question of the cybervirtue of a deck of cards is an interesting one precisely because for much of their history card games were expressly gambling games, and therefore seen as a quintessential expression of vice. Yet anyone who carries a deck of cards with them has the capacity to wile away spare time with engaging solitaire games that cultivate attentiveness (if not patience, per se), and an ability to create a convivial play experience for an arbitrary number of other humans who can be easily incorporated into the same cyborg network more or less at will. The deck of cards experience can be cyber-hospitable, cyber-disciplined, cyber-prudent, cyber-cunning, cyber-creative… the number of positive qualities that can be instilled by playing cards with other humans is far more than I suspect anyone else has ever thought about…I know most people in videogame development are more impressed by the latest computer specifications for high powered digital games consoles, but I can’t help myself: the deck of cards trumps all other multi-role game technology for its flexibility, its simplicity, and its potential to encourage virtue.

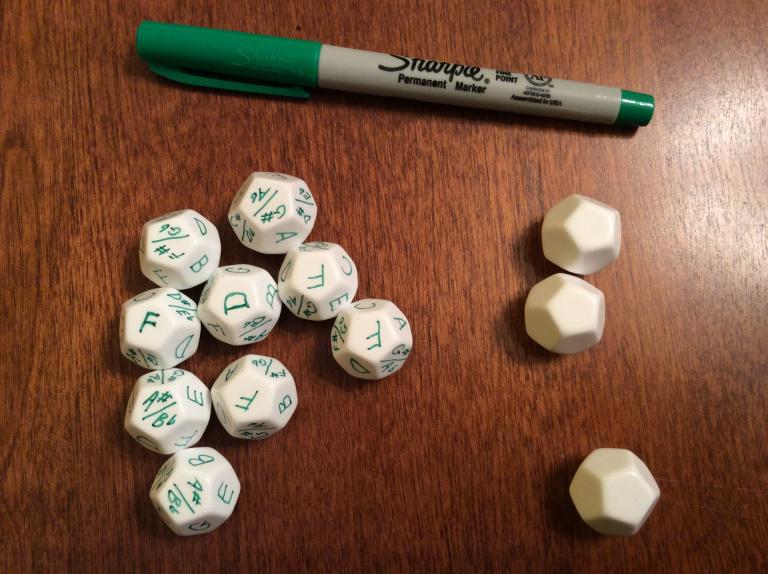

I was struck by this not just because of my general interest in gaming and gamification. I have been working on developing a game that can be used to teach and/or test music theory knowledge, and it began first as a deck of Playing Chords (a double pun, so I couldn’t resist) before transitioning into a set of twelve twelve-sided dice.

Below are the basic game rules that I have come up with. I am still trying to think of a good name for the game. If it were not for the intellectual property violation that would result, I might have called it “Do Re Mi Fa So Yahtzee! Do”!

Dodecaphonic Dodecahedrons

A Game of Musical Dice

Roll twelve twelve sided dice. Keep some as they are, reroll the rest. Do that one more time, then score.

You get the points listed if you roll something the first attempt; half that if it takes a second roll; a quarter if it happens on the third roll.

Each player does that, then you see who wins that round.

The first player to win the number of rounds you have decided on wins.

Simple!

Scoring:

Chromatic scale (every die is different): 1000 points

Black keys (every die has sharps/flats): 800 points

White keys (no accidentals on any of the twelve dice, no sharps or flats, only letters): 600 points

Chords: dice with alternating letter names (see additional rules below for important details)

Chords: dice with alternating letter names (see additional rules below for important details)

13 chord (7 alternating letters): 300 points

11 chord (6 alternating letters): 220 points

9 chord (5 alternating letters): 100 points

7 chord (4 alternating letters): 40 points

Triad (3 alternating letters): 16 points

Unison: # of identical dice x 10 points (not counting one of them)

Hexachords: 10 points for any series of six different notes

Tetrachords: 6 points for any series of four different notes

Intervals: 1 point per two dice with any different notes on them (count as many pairs as there are, as long as no die is counted twice)

Additional rules:

When determining alternating letters, after G you return to A. You cannot combine letters marked with sharp # and letters marked with flat b in the same chord.

You are allowed to set aside dice from a roll and then reroll the others, cutting your final score for the turn in half each time you do so. Once a die has been set aside, it cannot be rerolled on that turn, even if other dice from the first roll set have been repurposed after subsequent rolls to form part of a different scoring combination than you originally planned. Your score for your turn will be based on whatever one scoring combination you choose from among your dice rolls.

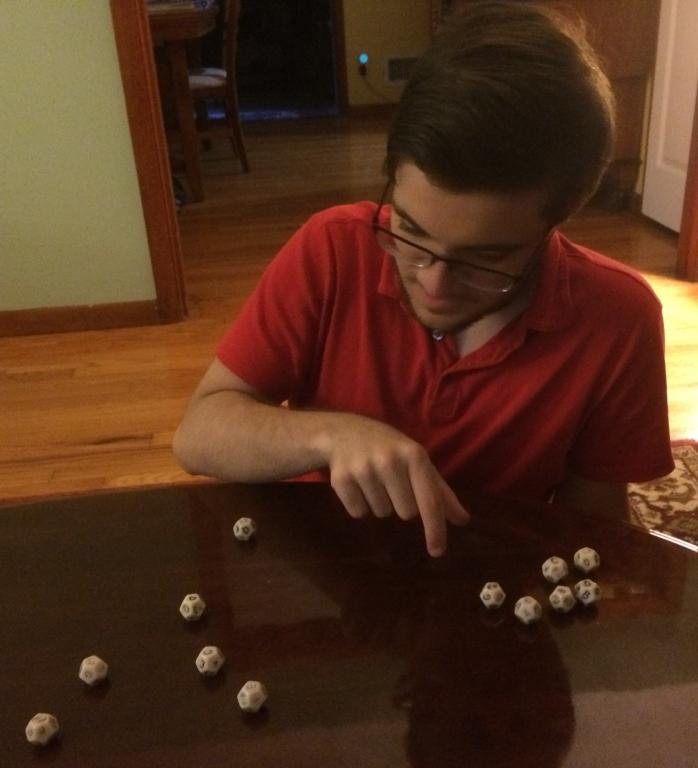

You can also add in scales for advanced players. The game as it is will let someone learn some basics of music theory without even knowing that that is what they are doing, just by learning the game rules as something arbitrary, much as is done with a game like poker. But it can also be used to test and build on existing knowledge, as happened when I played the game with my son and we found ourselves Googling to try to figure out whether certain combinations might exist as exotic non-western scales!

You can also add in scales for advanced players. The game as it is will let someone learn some basics of music theory without even knowing that that is what they are doing, just by learning the game rules as something arbitrary, much as is done with a game like poker. But it can also be used to test and build on existing knowledge, as happened when I played the game with my son and we found ourselves Googling to try to figure out whether certain combinations might exist as exotic non-western scales!

For those who may be interested in exploring musical games further, you can purchase your own deck of Playing Chords from The Game Crafter, the same company that makes Canon: The Card Game. I have yet to find a way to make musical dice other than by hand, but if and when I do, I will make that available online. If you try playing the dice game or use the cards, let me know how your experience is!