I find myself really challenged by something Mike Duncan wrote on his blog Bad Rhetoric recently, noting the number of university-educated people who voted for Donald Trump. He writes:

I used to think my teaching was formative of critical thinking and ethics and built at least a motte and bailey defense against the worst excesses. Writing needed teaching to all comers as a communicative civil right. All that seems dangerously stupid now. Increased writing skill does not magically lead to responsible citizenship. If you knew 42% of your composition class was going to note your citizen-building pedagogy and vote for Donald Trump, would you not change your strategy? Or would you “do your job” to “teach writing” like thousands of others, especially as an adjunct or lecturer if you did not have a reasonably secure job or control over your curriculum?

Repeatedly, we have thrown the difficult and lengthy task of teaching skilled writing to instructors that were underprepared, underpaid, and overworked. When we surrendered collectively and unconditionally to the conclusion that the task was not important enough for the best trained, best paid, and best-motivated instructors – who got to become “scholars” with minor teaching responsibilities – that was when the seeds were planted. Now the entire country pays for our neglect; a constitutional crisis that makes Nixon look like a paragon of integrity. If we could have taught just 1% more responsibility – just 1% – Trump would not be president…

A college education, on the front lines of voting, may be the best hope for holding the democratic line, but blind idealism, our old pedagogical strategy, is not enough in the face of an evil that conceals its true nature all too well. There are many “anti-citizens” out there that think Trump is the second coming. Lower taxes, reduced immigration, tough trade talk, white male Supreme Court justices, racism and sexism carefully enshrined – all the little things they want, and at what they think is a great price, their souls bundled with the future.

You may note that I used the word evil. I did so purposefully. This is a path of evil we’re on. The election of Trump in 2016 was not a blip. It was a game-changer, a culmination of decades of poor education and careful politicking. Whatever happens in the midterms next month, even a Democratic takeover of both the House and the Senate, will not reverse it. It takes decades to make this kind of mess, and it will take decades to change it. I wonder, though, if we have decades left.

On the other hand, Steve Wiggins wrote recently:

[T]hose on the opposite side of the political spectrum rending the United States into shreds aren’t evil. They’re doing what they believe is right, just like the lefties are. The evil comes from forces trying to tear good people on both sides apart…Evil is the desire for political power that draws its energy from making each group think the other is evil.

I appreciate both points, and they lie at the heart of the challenge of formulating a Christian (or more generally, an ethical) response to the current political climate. We are supposed to love all and forgive enemies. We are supposed to treat those who treat us poorly with kindness. And we are also supposed to actively seek justice and peace. How are we supposed to navigate those two commitments?

Adam Serwer wrote an article about something that can, I am sure, be found across the political spectrum, but is predominating very clearly on one side more than the other these days, namely the penchant for outright insult and mockery of those who appear to be not merely disagreed with, but hated or viewed with contempt. And so the fact that Christians must be committed to loving enemies, to seeking the redemption rather than the destruction of evildoers, doesn’t mean that we evaluate all politicians, all parties, or all people and organizations of any sort as though they are alike. The differences matters, even while so too does recognizing our common humanity and that we all have sinned and all have value.

Being politically, socially, economically, and/or technologically engaged is messy and seems to inherently involve compromise. One can go live in the wilderness in remote regions and not be implicated in the economic wrongdoing that is inherent in the processes that put food on our tables in the nations we currently live in, and cut ties with all social media that are doing wrong. But cutting all ties does not challenge, much less change or bring about the downfall of, these problematic institutions and corporations. And so the effort to remain personally innocent in one sense makes us culpable of not getting into the messy trenches of combating injustice in another. Just as not voting because no candidate is perfect may let greater injustice prevail.

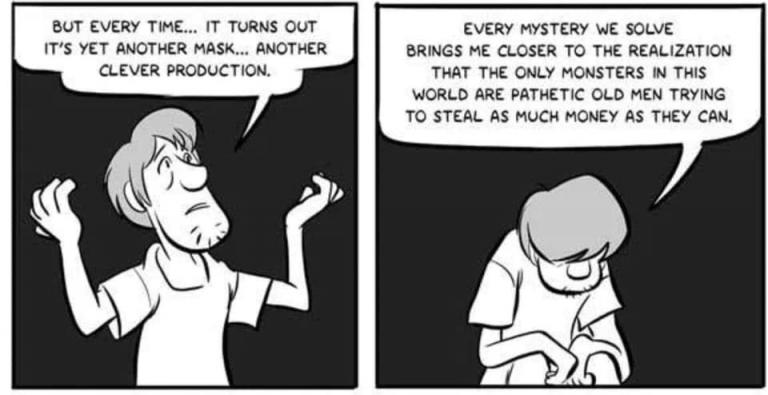

Bill Heroman shared this image (the source of which I could not initially trace, but then had a commenter helpfully track down as coming from Pedro Arizpe):

That’s one of the reasons that I love Doctor Who (and other science fiction that does something similar) is its penchant for helping us to see beyond appearances that might lead us to stereotype others as monsters – or to assume that those who resemble us and seem attractive are not monsters. We cannot forget that those we are inclined to view as monsters and/or demonize are human beings like us. In most instances, they do not think of themselves as evildoers. They think they are being caring, protecting their own group at the expense of others, often assuming that is the only way to proceed in a hostile world.

Returning to the topic of university education which was our starting point, it needs to be pointed out nowadays that the “liberal” in “Liberal Arts” is not about political or theological liberalism. But that doesn’t make them “value free.” The very act of appreciating genuine diversity of thought, open dialogue across difference, and critically evaluating one’s own views in addition to those of others involves a value judgment and commitment.

A great many sources have been discussing why the humanities and the liberal arts matter now more than ever. But is the reason because they lead us to include those who would seek to exclude others, because they enable us to combat exclusivism with a different sort of exclusivism, of because they help us to recognize that the complexity of balancing and at times prioritizing multiple goods and values is challenging and not susceptible to easy answers?

At a time when a number of institutions are cutting core curriculum, general education, liberal arts, and/or humanities programs, my own impression is that we need them more than ever if we hope that our students’ technical and professional skills are going to be used in a compassionate, caring, and ethical manner.

Don’t miss that I’ve included lots of links to articles about these and related topics throughout this post. I also want to mention how much I valued the institute focused on diversity, civility, and the liberal arts which The Council of Independent Colleges held in Atlanta, Georgia over the summer. I was delighted to have been among those chosen to represent Butler University there, and it was an honor and privilege for Butler to be chosen as one of the institutions to participate. I learned a lot, including things that proved relevant to the work on ethics and computer science that I have been engaged in. The topic of prioritizing values is continuing to be to the fore in things that I am thinking and writing about.

Also of related interest, John MacDonald shared some thoughts on evil and chaos, Darth Sidious vs. the Joker.