The Jesus Creed blog shared a number of principles for biblical interpretation from John Walton, the deservedly renowned evangelical biblical scholar. While a number of principles are shared related to a number of different aspects of how religious believers approach the Bible, it is the methodological commitments that I think are particularly worthy of being given wide circulation. Here they are:

Methodological Commitments.

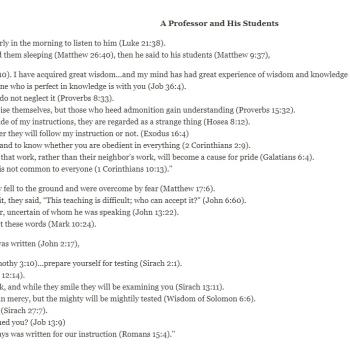

- We must allow the text to pursue its own agenda, not force it to pursue ours.

- We must be committed to the intention of the author rather than getting whatever mileage we can out of the words he used.

- We must resist over interpreting the text in order to derive the angle we are seeking.

- We must be willing to have our minds changed by the text – that is at least part of the definition of submitting ourselves to the authority of the text.

- We must be willing to accept the inevitable disappointment if the text does not address or solve the questions we would like answers to.

These are all important guidelines to keep in mind. We shouldn’t hijack the text, commandeering it for our own purposes.

Check out the blog post on Jesus Creed for the rest of what is offered there. It is worth reflecting on these “shoulds” and “shouldn’ts.” These aren’t conclusions that can be tested scientifically in a test tube or lab experiment. They are value commitments. Not only biblical interpretation as practiced by the mainstream academy, in most seminaries as well as secular colleges and universities, but the entire educational endeavor in most institutions of higher education, does not unfold in an abstract manner that simply is. It is carried out in a way that reflects our values, our conviction that there is merit to subjecting even our most sacred texts and dogmas, our most cherished assumptions and ideas, to close scrutiny and cross-examination.

This statement by Allan Bevere also seems like a good principle for religious believers to follow:

On the one hand, the tensions cannot and should not be smoothed over to protect Scripture; and on the other hand, Scriptures we don’t like cannot simply be dismissed in order to protect God’s character. We should not seek for easy answers, and we must take the entire canon of Scripture into account.

A United Methodist minister urged caution when using the Bible. See also Hillel Halkin’s interesting argument that it is impossible to read the Bible “as literature.” And Marti Steussy from here in Indianapolis was interviewed for an article in the Indianapolis Recorder. Here is an excerpt:

There are also literary benefits to learning how to read the Bible in its original language. Marti Steussy, who is retired but still teaches a few Greek and Hebrew courses at Christian Theological Seminary, said many of the Bible’s authors have distinct voices that tend to get lost when translated into English. Take Jesus, for example.

“His ability to play a soundbite is amazing,” Steussy said of his Sermon on the Mount. “We sort of miss that.”

Steussy said one misconception people have is that learning how to apply the original language to the Bible will answer all the questions they’ve ever had. But Steussy noted Greek and Hebrew, just like English, have words and sentence structures that a reader can interpret in a number of ways.

Steve Wiggins wrote about the things we instinctively know when reading a newspaper that we are prone to forget when reading the Bible, and the importance of context. See as well Keith Giles’ post with the title “I Never Go To The Bible For Wisdom: Because The Bible Tells Me Not To,” Richard Beck on progressives who are triggered by the Bible, the book review of Inconsistency in the Torah, the editorial about How the Bible is Written, and the continuing series by Internet Monk on Pete Enns’ book.