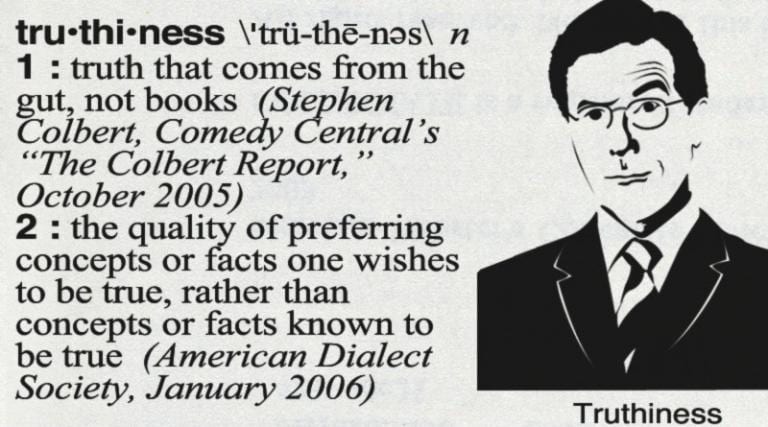

I remain indebted to Stephen Colbert for coming up with the concept of ‘truthiness’. As a religion professor, I find this term denotes the most common hurdle students face in trying to do any kind of critical thinking, much less about religion. How can there be any historical uncertainty, much less doubt, about the details of the Exodus from Egypt, or the life of Jesus, when it feels so right?

Let me simply reiterate the statement attributed to Jesus in John’s Gospel: “You will know the truth, and the truth will set you free”. For a historian, whether or not Jesus said these words is uncertain: they are found only in John’s Gospel, and the words placed on the lips of Jesus in this Gospel match the author’s own style. For many Christians, these historical questions are either completely foreign to them – things they have never even heard, much less thought about – or they are indications of doubt, skepticism and unbelief. Yet if one believes that the truth will make us free, then the truth cannot be something that we explore only subjectively with our hearts. The heart and the head cannot be separated – well they can when you are talking literally, but I’m using this language metaphorically here!!! If we fear exploring historical, scientific, psychological and other questions because they will challenge our beliefs, we do not have the truth. We have truthiness. Of course, you might just happen to have the truth, but so might the people you disagree with. The only way to find out is to dare to think, to explore, to examine. Someone once said that you never truly believe something until you have looked seriously at the views of those who disagree with you. This is the path that leads beyond truthiness to truth. I encourage and indeed applaud anyone brave enough to take that path.

A helpful summation of how this works in practice is provided by Parker Palmer in The Courage to Teach:

[T]he only “objective” knowledge we possess is the knowledge that comes from a community of people looking at a subject and debating their observations within a consensual framework of procedural rules. I know of no field, from science to religion, where what we regard as objective knowledge did not emerge from long and complex communal discourse that continues to this day.

The firmest foundation of all our knowledge is the community of truth itself. This community can never offer us ultimate certainty – not because its process is flawed but because certainty is beyond the grasp of finite hearts and minds. Yet this community can do much to rescue us from ignorance, bias, and self-deception if we are willing to submit our assumptions, our observations, our theories – indeed, ourselves – to its scrutiny.

(Most of the above was written May 2006)

Of related interest:

Pursue the Truth, and Run Like Hell from Anyone Who Claims to Have It