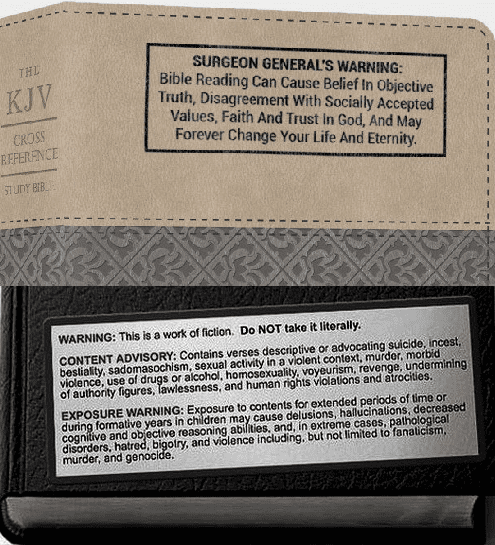

We live in an era when we have become accustomed to information about the contents of foods, movies, CDs, and other things to be on the packaging. I’ve blogged before about what warning labels it might be deemed appropriate to put on Bibles. Compare these two, which you can find online along with a number of others, which I’ve set side by side here to contrast them more effectively:

The question I want to tackle here is whether one of these is a “side effect” and the other is what this medicine is supposed to do.

I suspect that most people whose experiences of religion have not been extreme and unusual would acknowledge, if they are honest, that there are benefits and downsides. Community, encouragement, hope, motivation, introspection, humility. Dogmatism, inflexibility, divisiveness, hate. How can these same results come from the same religious tradition? Part of it may be the classic fact that (as the saying goes) “your mileage/experience may vary.” Part of it is that the same substance may be used in very different ways, as remedy in moderation or as destructive addiction when abused. There may be a variety of high-quality products that are safe but cheap imitations that are dangerous. When it comes to religion in general, any or all of the above applies at times. However some doctrines, denominations, pastors, priests, and texts provide ample evidence of being simply dangerous, detrimental to wellbeing even in moderation. Unlike medicine, there is no government oversight or regulation of religion that might attach warning labels. The most dangerous forms, ironically, are the ones that offer the most warnings about the supposed dangers of everyone else besides themselves. Simply looking into the matter online or by talking to people you know won’t be a safe guide unless one has well-honed information literacy skills. Just as with matters of politics and medicine, so too with religion, people are happy to draw broad conclusions based on insufficient evidence, whether in the form of internet search results or anecdotal experience.

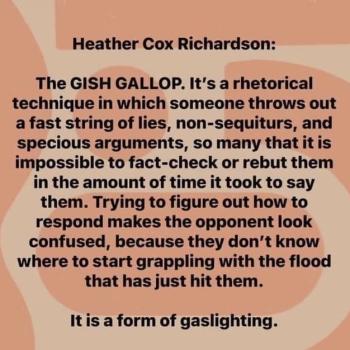

Danny Anderson wrote an extremely insightful piece recently called “Conspiracy Theory as Evangelical Liturgy” that I highly recommend everyone read. This excerpt sums up its main point, but it is the details that make the case:

The rise of conspiratorial thinking in Evangelical churches is not a bug, but a feature.

The same mainstream, reasonable Christian culture which is now publicly embarrassed by the flock’s enthusiasm for Q have, for the last 50 years at least, not only tolerated, but actively encouraged conspiratorial thinking every bit as ridiculous as that of the Satanic, pedophile-hunting, Deep State-battling Q narrative.

The “Q” being referred to is of course QAnon and not the Two-Source Hypothesis as solution to the Synoptic Problem. Conservative Christianity has trained people to think in particular ways, and thus the spread of political misinformation in those communities should not seem unexpected. To connect that to the theme of this post, embrace of a conspiracy theory mode of thinking is not a side effect but the intended effect of the “medicine” of conservative Christian teaching and culture. Embracing specific political conspiracy theories may be a side effect, but that is a direct result of what this “medicine” is designed to do, much as taking a sleep aid impairs driving. That isn’t a happenstance side effect that one tolerates because of something else the medication does. That is because the medication is doing precisely what it has been developed to. You cannot train people to reject mainstream scientists, journalism, scholarship, and ethics and then be genuinely surprised when they do precisely that. That you did not want or intend them to do so when you trained them to think in these ways is your mistake, an error of judgment for which you are culpable if you played a part in fostering this mindset. Rejection of authority is a genie that religious and political leaders regularly let out of its bottle, thinking that they can control it. But conspiracy theory thinking is highly addictive and turns out to also be contagious. It is less like mainstream medicine, and more like the kind of thing that conspiracy theorists falsely claim about the COVID-19 vaccines that have been developed. Conspiracy thinking doesn’t rewrite your DNA any more than any vaccine does outside of the realm of science fiction. But conspiracy thinking does train you to be vulnerable to being misled in more than one way, and on more than one occasion. Once you’ve started, you’re unlikely to stop unless you recognize there is a problem and seek a cure.

So what kind of warning label should religions, their texts, and their doctrines carry, if any? At this point, let me quote something that Rev. Jim Rigby wrote some years ago:

I love the Bible and study it most days, but the Bible is not intended to be a substitute for a functioning human brain or heart.

I do not believe the sun rotates around the earth just because the Bible says that Joshua stopped the sun. I do not believe the mustard seed is the smallest seed even though Jesus said that it was.

The stories of the Bible can give communities a common vocabulary to talk about what it means a human being in the cosmos, but the Bible is not a reliable guide for science, or for history, or sometimes even for ethics.

The Bible says we are responsible for our own actions, which means we are also responsible for our own thinking. If the Bible can be wrong about astronomy and horticulture, it can also be wrong about slavery, evolution, women and homosexuality.

As the Bible itself warns, if anything (including our interpretation of the Bible) makes us loving, it is right; but if anything (including our interpretation of the Bible) makes us cruel, it is wrong.

That’s the kind of warning label I’d want to see placed on Bibles and on religions. But the truth is that if people took responsibility for drawing their own conclusions while also humbly recognizing their own need to rely on the expertise of others, warning labels probably wouldn’t be necessary. Not on scriptures and religions, at any rate.

In other words, to put it even more briefly and echo another famous warning:

RELIGION RESPONSIBLY

Of related interest see also:

https://thewayofimprovement.com/2020/11/27/david-brooks-on-the-gops-detachment-from-reality/

https://thewayofimprovement.com/2020/11/27/the-court-evangelicals-and-the-5-stages-of-grief/

https://thewayofimprovement.com/2020/11/26/some-court-evangelicals-are-still-keep-pushing-the-voter-fraud-narrative-others-are-angry-with-obama/