Most will know of the myth of Proserpina who, while picking flowers near Enna in Sicily, was seized by Dis and carried away in His chariot by black steeds. Ceres searched high and low for Her daughter Proserpina, calling upon other Gods and Goddesses to join in Her search but none dared. Proserpina’s father is Jupiter, who had given Her in marriage to His brother Dis. Upon eating a single seed from a pomegranate, symbola of female fertility, Proserpina was committed to remain as Queen in the Underworld of Dis Pater. But Ceres withdrew Her benevolent effect on earth as She mourned the loss of Her daughter. The earth suffered under its first winter. It became barren. People starved and plague spread. The paternal Gods became distressed with such suffering and thus a bargain was made where Proserpina would spend only the winter months with Dis and, come spring, would return to live with Her mother Ceres.

This myth of Ceres and Proserpina can be interpreted on different levels. Mother Ceres is the Goddess of wheat, and Her daughter Proserpina is Her seed. Thus the myth can be seen as an allegory for the planting of winter wheat into the ground in October. Interestingly the petroglyphs of the Val Camonica region that date back to the Bronze Age show scenes of naked men plowing fields as women on the side have their hands raised above their heads as though wailing, or some might see them as praying. The myth also holds something of a marriage, and the marriage rites of ancient Rome included a mock seizure of the bride by her groom, to re-enact Dis’ taking Proserpina, before carrying her away to his house. The bride was led through the streets at night, proceeded by torch-bearers of Ceres, just as She had searched by torch light at night for Her daughter. And, “plowing the field” was a common euphemism among Romans for coitus. The close connection of fertility in women with fertility of the land is a one theme in the myth and in the rites of October. The descent of Proserpina into the Underworld, and Her subsequent return in spring, holds themes on the change of seasons and on the cycle of birth, death, and rebirth. But I don’t know that many realize how the two are interlinked. The “world” as the ancients thought of it was what we would think today as our solar system, at least those parts that are visible to the naked eye. This world rested within a boundary of the fixed stars and was divided by the celestial equator. The sun and planets, however, travel along the ecliptic on a path that leads them into the upper portion and down again below the celestial equator into the Underworld. The sun moves further and further north as earth is tipped towards it in winter, and it enters that portion of the Zodiac that lies in the Underworld. The ancients believed that the Milky Way was the souls of the dead as they traveled through the Underworld to rise either into the heavens to live near the Gods as semi-divine Lares or else to return down to the world once more. The Gates where one enters or returns from the Underworld are those points where the celestial equator intersects with the ecliptic. The whole story of this journey can be seen only on one night in the year, at the winter solstice, to which I shall return at another time. I might go on with more about the myth, its different versions, and the way it was interpreted, but my point here is only to say how the myth and its allegorical themes informed both ancient rituals and modern rituals for Ceres in October.

On a night in early October, shortly before 217 BCE, the Roman mysteries of Ceres were introduced to the Eternal City from Campania. They were said to be “Greek,” however they bear no resemblance to the rites of Eleusis nor of any other Greek festivals for Demeter. This Sacrum Anniversum Cereris was a unique innovation to Rome, mainly because the rites were held exclusively by women. For nine days prior to the rite, concluding on 4 October, women performed purification rituals, abstinence, and fasted from dawn to dusk, partaking only in the agnus castus (chaste lamb) during those hours. Agnus castus is a drink made with honey and rosemary infused in water. Named as matrons and virgins, mothers and daughters, wives and sisters, the women seem to have been paired to reflect Ceres and Her daughter Proserpina. In the early hours of 5 October some of the women, presumably the ‘mothers,’ would gather at crossroads throughout the City. They bore torches, just as Ceres had used in Her frantic search for Her daughter. Three times the women would call out to Proserpina. Then they began to run throughout the City, calling after Proserpina three times as each group of women came to a crossroad. Then after dawn they could be found sitting in the streets, wearing black and mourning the loss of Proserpina. Ceres was offered wine and poppies to soothe Her sorrow, and the women may have also been served a drink of poppies.

On the following day the marriage of Proserpina to Dis Pater was remembered. The women would don pure white robes as though they were brides. Their veils were held in place by woolen fillets of Ceres. Some wore the corona spicae, or “crown of wheat,” in conjunction with the early morning rise of Corona Borealis. The women then paraded through the streets of Rome in a public display of female chastity.

Very closely linked in the religio Romana is a relationship between ritual purity and fertility. The seed of a child is a gift from the Gods, and thus women must be ritually pure to receive this gift. The same is thought true of men, that their virility is a gift which only comes from a pure life. At this festival, as with the Lupercalia of February, this idea is taken a step further since the restoration of virginity in women through purification and chastity was believed to ensure the fertility of the land as well, and thus women, not men, ensure the promise of another growing season ahead benefits the entire community. Therefore, on the third day of the festival a thanksgiving is held for Ceres, where grain, flour, and bread are offered to Her in anticipation of desired produce from the fields. Also offered is the praementium wreath made of thick, tightly bound stalks of spelt-wheat that also represents the wheat and other farm produce we hope to harvest in the coming seasons.

The earliest ritual that I can recall being instructed on, so that I might perform it myself on behalf of the family, was in conjunction with our October festival for Ceres Ferentia. My mother taught me about the spirits of the land, the geni loci, who would help us in our garden if only we might plant some garlic in autumn so that they might nibble at the roots over winter. In this way they would be sure to remain with us until spring. And so a little tomb was dug for each of the garlic cloves, each buried separately, with a libation of a little wine poured over them. Planting in the fall, with the first shoots coming up in early spring, was a tangible lesson for a four year old boy to learn. It has informed my conception of Nature through many years of life, taught me how to deal with the transitions that come in life, and even how to face death as a transition over to a new life. And so today, too, my October rites for Ceres, to benefit my garden and all those it may feed or heal, includes a rite of planting along with other rites.

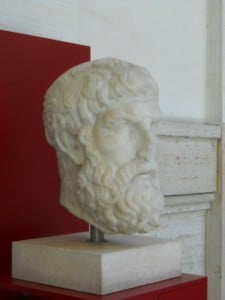

If you plow a field, or roto-till a garden, you will turn up soil alongside your furrows. Stones are brought up out of the soil and these, large and small, are gathered up at the end of the furrows to form a small altar. The wood for these fires is Sicilian plane tree, also call sycamore in the Americas, that represent the island from which Proserpina was taken. At the end of each furrow, then, offerings are placed of penny royal, mint, and meadowsweet as incense, along with kernels of wheat or barley and poppy heads. At the other end of my furrows stands a bronze statue of Ceres. At first She is dressed as though She is Proserpina. An altar is erected before Her image and gifts of honeyed milk, flowers, wheat, bread, herbs from Her garden, along with other produce of the garden, and a pomegranate are presented on an offering tray of copper. Corn dolls representing Dis Pater and Proserpina are also on the tray. These are hung in a tree behind the statue of Ceres to represent the wedding party. Only the incense and a libation of milk and honey are offered first.

Next, using a bronze blade, the ends of the furrows that face Ceres are cut to form a crevice in each that are said to resemble the pudenda of Proserpina. In ancient times a piglet would be sacrificed, it too being compared to the pudenda of a virgin, and its blood poured into these crevices for the Manes of the earth. Today wine is substituted for blood, following the proscription against blood sacrifices that Numa Pompilius first instituted some 2670 years ago. Then seeds are sown. These may be cold weather crops like rabbia, cauliflower, broccoli, or cabbage, to come up early next year. Or they may be flowers or herb seeds. This year I sowed poppies and basil. And like Pliny tells us, when sowing rabbia, we do so with a little prayer, Hoc papaveram mihi vico sereo. “This poppy I sow for mine and my neighbors.”

Between the beginning and the end of the sacrificatio, some sow seeds, praying as they do so. Meanwhile at the main altar one acting as sacerdos offers a hymn of praise for Ceres:

“O most holy Ceres, nurturing Mother, whose sacred womb gave birth to both Gods and men; You, Vervactor, who first yoked the oxen and placed the ploughshare to virgin soil; You, Reparator, who first prepared furrows in fallow land; You, Imporcitor, who first made wide our furrows; You, Insitor, who first cast Your bounty on the earth and taught the seed to grow; Obarator, Sarritor, Subruncinator, and You, Sterculinia, who first cared for crops; You, Flora, who make the grain to bear fruit; You, Messitor, who first set scythe to grain stalks; You, Convector, who first spread grain on the sacred harvest floor; You, Noduterentor, who first showed us how to thresh, and You, most holy Ceres, whose very breath separates the white chaff from the golden grain; You, Conditor and Tutilina, who guard the grain in storage; You, Promitor, who first milled the grain and distributed its flour for our daily bread; You, eternal savior, Ceres, lavishing Your bounty upon me and mine, to You, flaxen-haired Ceres, gladly I give thanks and praise, and, from the little I have, to You I willingly make an offering. Accept these, the first fruits of my fields. May my offering incline You more towards me. May You ever nourish me and mine with Your bounty, O most holy and nurturing Mother, gentle Ceres.”

With the seed planted, the image of Ceres is then dressed in Her garments of mourning. She is veiled in black, both outdoors and at Her shrine indoors. It is then that offerings of bread and wheat are placed on the altar, along with wine steeped with poppies as a libation, and mints and pennyroyal included as incense once more. A meal is served with a place set for Ceres. She does not eat of it, though, while She weeps for Proserpina. Afterward the bones of the meal are gathered up, placed in an unfired clay jar and buried in the field. By evening a final glass of wine and poppies are pour on the ground, oil lamps are lit for Ceres, and we depart.

If it sounds like a somber ritual, it may be because this is a sowing ritual, rather than a harvest festival. Harvest festivals took place earlier, at the end of work in September, and now we begin a new cycle. This is instead a ritual that revolves around the work. Ceres is called upon in Her many aspects to help in the work of tilling and sowing and She will be called upon again in spring as the soil is tilled, sown, and fertilized once again. The colors of Autumn burst forth, reminding us of the Spring to come with the snows of winter giving way to warm breezes of March. Life changes with the seasons and the seasons bring us promise of anew life.

Valete, comreligiosi, in pace Cereri. Di Deaeque vos bene ament.