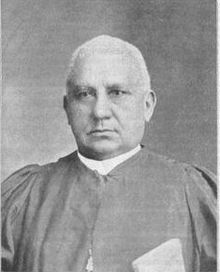

In recognition of the 100th anniversary of the death of Bishop Henry McNeal Turner (February 1, 1834-May 8, 2015).

*Below is an edited version of a paper that I presented at the Colored Convention Symposium on April 25, 2015 in Newark, Delaware at the Delaware Historical Society Reading Room. This is part 1 of the presentation.

Introduction

In August of 1893, African Methodist Episcopal (AME) church bishop, Henry McNeal Turner, issued a call to convene a black national convention. This in and of itself was not anything out of the ordinary because there had been black national conventions held since 1830. However, two things made this one special. First, it had been four years since the last national African American convention of any kind during that time; many states nullified the political gains of African Americans.

Second, this convention would be special because among the items that were normally discussed at these conventions; racism, equality, fair treatment and better accommodations, there would be one more. The delegates were going to discuss the merits of emigration, either Africa or somewhere else. For Bishop Turner the time had come for black Americans to seriously consider moving out of America. Turner stated in the call

I do not believe that there is any manhood future in this country for the Negro, and that his future existence, to say nothing of his future happiness, will depend upon his nationalization….But knowing that thousands and tens of thousands see our present conditions and our future about as I do, and after waiting for four years or more for some of our colored statesmen or leaders to call a national convention or to propose some plan of speaking to the nation or to the world, or to project some measure that will remedy our condition, or will even suggest a remedy, and finding no one among the anti-emigrational party or anti-Negro nationalization party disposed to do so, and believing that further silence is not only a disgrace but a crime, I have resolved to issue a call in the near future for a national convention to be held in the city of Cincinnati, where a spacious edifice is at our disposal, to meet some time in November, for the friends of African repatriation or Negro nationalization elsewhere, to assemble and adopt such measures for our actions as may commend themselves to our better judgment (Respect Black 146).

Even though the convention was well attended and received considerable coverage from the black press, the convention, in Turner’s eyes, was deemed a failure. Instead of a “radical plan” for emigration, the only recommendations that came out of the convention were to establish the National Equal Rights Council, with Turner acting as “chancellor” and to continue to appeal to Congress, governors, and the American people for fair and equal justice.

In this presentation, I will attempt critically to assess the propaganda of Turner’s emigration plan. Moreover, I will attempt to show where Turner’s propaganda achieved its goals and where Turner’s propaganda campaign failed—namely the oppositional counter propaganda campaign offered by other African American leaders who argued that emigration was a foolish proposition. However, first, I will attempt to sketch Turner’s involvement in the Colored Convention movement.

Turner and the Colored Conventions

Turner was a prime mover in the Colored Convention movements on the national, state and local levels. One of the first was a local convention called the Contraband Convention held in Washington DC during the Civil War. Held at different churches throughout the city, the weekly convention gatherings aimed at helping formerly enslaved people with food, clothing, and any other necessities. Turner wrote about one of those meetings in which the delegates decided to raise money for a hospital.

The colored convention met at Zion Wesley Church, on Tuesday night last, and resolved upon the erection, as soon as possible of a hospital for the sick, afflicted, and destitute. They resolved that each delegate should advance ten dollars, as a beginning, to the sum of $5000, which they think will be required to complete the object in contemplation (Johnson, Vol. 1, 149).

However, plans for the hospital apparently fell through as Turner noted in a follow up letter to the editor.

I am sorry to inform you that the convention for the erection of a hospital, has come to no decisive point. I was informed that a residentiary question had staggered its contemplated measures. But I think the indifference of the members to the call of the President, Mr. Wm. Slade, has done more harm that the question of residence, though I regard the entire residential question as foolishness, unless, they are going to build the hospital, and generally such agitators give the least (Johnson, Vol.1, 163).

After the war, Turner moved to Georgia and quickly became involve with politics. Writing about the state Equal Rights and Education Convention held in October of 1866, Turner praised the work of the delegates.

The convention of colored men from all parts of the State, which was held here a few weeks since, did honor to our race, and exhibited a degree of progress intellectually, and highly commendable, in a people so recently freed. There was marked ability developed in their entire proceedings, the idea that colored men could not govern themselves, if permitted, is all a hoax. The addresses which they prepared and memorialized the legislature with, will stand as a monument of colored ability in Georgia for centuries (Johnson, Vol 3, 25).

After the white representatives of the Georgia Legislature vote to remove the black reps from office in 1868, Turner issued a call for a state convention. After listing grievances and naming the reasons for such action Turner concluded

In view of this state of things, we call upon the colored men of every county in this state to send delegates to a state convention of colored citizens, to be held in the city of Macon, on the first Tuesday in October, 1868, for the purpose of taking into consideration our condition, and determining upon the best course for the future. There can be no doubt that our personal liberty is in as great danger as our civil and political rights. The same power which would override the constitution in one thing will do it in another. It is, therefore, a solemn duty which every colored man owes to himself, his family, and his country, to maintain his manhood and his right of citizenship. (Johnson, Vol. 3, 166).

Later that year in December, Turner testified before a Congressional hearing on the Reconstruction efforts in the state of Georgia. He acknowledged that he was not only a member of that convention but also served as president. When George Boutwell of Massachusetts asked “did the convention represent the Negro population of the State pretty extensively,” Turner responded

Very extensively. There were not members from all the counties. The poverty of our people was so great that in some instances two counties joined together and sent one man to represent them both. One hundred and eighty delegates were present from all parts of the State. What is known in Georgia as “the negro belt” was well represented; I mean the middle and southern parts of the State. Several of our delegates had to walk 50 or 60 miles; and one man, I think, walked 105 miles to get to the convention, owing to the fact that neither he nor his constituents were able to pay his fare there by railroad (Johnson, Vol 3, 199).

Turner further noted that the convention appointed a special committee on “murder and outrages” which every member submitted a report. “A synopsis of the report was made by the committee,” Turner continued, “which I would be glad to place in the hands of this committee if they will allow me.” Turner also added that “if I had known that I would be called upon by the committee to make a statement in regard to the condition of the colored people, being president of the Civil Rights Association, and receiving letters and reports from all parts of the state, I could have laid before you an immense mass of documents on that subject”. (Johnson, Vol 3, 199-200)

In 1871, Turner called for African Americans to hold another state convention in Atlanta to address the results of recent elections in which Democrats took control of the state house. “Whatever is done,”wrote Turner, “must, in order to be effective, be the work of mature deliberation, where all the statesmanship, experience, and intellectual sagacity in our possession can be brought into requisition (Johnson, Vol. 3, 171).

Again, Turner found himself before Congress testifying about the conditions of African Americans when the subject of the Southern States convention in 1871 arose. When asked about how many murders have been committed in the state since the spring of 1868 Turner responded:

We held a Southern States convention week before last in Columbia, South Carolina, at which place there were delegates from all the Southern States. We meet together at the request of the committee on murders and outrages, and according to the best of our knowledge and belief it was estimated that since reconstruction between fifteen hundred and sixteen hundred had been perpetrated (Johnson, Vol 3, 224).

When his interlocutor asked “in the South” Turner answered, “No, in the state of Georgia.” When pressed on how many murders have happened in all the southern states since 1868, Turner responded that it had not been “less than twenty thousand.” That number, Turner noted, was what delegates had agreed upon based from the reporting that each delegate made to the “murder and outrages” committee (Johnson, Vol 3, 224)

Even when the colored convention movement was about to wane, Turner thought conventions were still important

I think it was a great mistake to abolish colored conventions, if it was done at the biding of Mr. Douglas, that prince of negroes. A national colored convention has been greatly needed for the last several years. If the Northern negro is satisfied with matters and things, we of the South are far from being. Indeed I have been thinking of calling one for the last twelve months; not political but a civil and moral convention. Gov. Pinchbeck said to me, a few years ago, that the colored people should hold a national convention every three or four years if they could to have grievances and complaints. Such a convention is needed more, yes far more needed, than any mere self-improvised committees (Johnson, Forthcoming. Vol. 4, 22).

Ten years later, Turner again called for a national convention.

Read Part 2 here