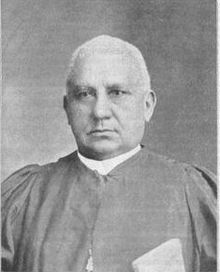

In recognition of the 100th anniversary of the death of Bishop Henry McNeal Turner (February 1, 1834-May 8, 2015).

*Below is an edited version of a paper that I presented at the Colored Convention Symposium on April 25, 2015 in Newark, Delaware at the Delaware Historical Society Reading Room. This is part 2 of the presentation. Read part 1 here.

Turner’s Propaganda Campaign

After his initial call to the 1893 Convention, the response was overwhelming. Turner wrote in his newspaper that over “three-hundred responsible Negroes had endorsed the call and that delegates from all over the world would attend” (Black Exodus 185). Even though Turner called for a “Black National Convention, the convention itself became known as “Turner’s Convention.” He was the leader, the architect, and convener.

At the start of the convention about eight hundred delegates were registered along with many local blacks from the host city Cincinnati. The attendance was even better than Turner originally expected. Many of them had all come to hear Bishop Turner’s opening address. The address itself was vintage Turner. He reminds his listeners that blacks, or the “specific race” he speaks of, in the past have been faithful and loyal citizens, but it’s all been in vain.

At the end of Turner’s speech, the audience erupted in applause and praise. Throughout Turner’s speech the audience shouted and cheered. However, by the end of the convention it was clear that the overwhelming majority of delegates were not in favor of emigration and nothing more ever came from the convention.

The Failure of Turner’s Propaganda Plan

Drawing on Jacque Ellul’s study of propaganda, one notices several reasons why Turner’s propaganda campaign failed. However, acknowledging the failures, there was some “good propaganda” in his campaign. First Turner’s propaganda exhibited the external characteristics of propaganda. Turner’s propaganda always was directed both at the individual and the group. Blacks were already separated and all deemed second class citizens, whether one lived in the North or the South. So when Turner spoke about injustices, lynching, degradation and all manners of violence directed at the Negro, the individual and the group could agree.

Second, Turner’s propaganda was total. Not only did he use his newspaper, but also as a Bishop in the AME church, Turner traveled all over the church districts espousing his vision and beliefs. What Turner wrote or said was repeated in pulpits all across the South as well as in the North. Turner became so popular that many of his sermons and speeches were printed in other newspapers, both black and white. Any medium that was available to Turner during his lifetime was used.

Third, Turner’s propaganda was also continuous and lasting. Everywhere Turner went, his preached and taught on emigration. Turner’s propaganda was also organized through the AME church. It was through the church Turner had at his disposal his paper, The Voice of Missions and also The Christian Recorder. Therefore, anywhere Turner was to speak, any conference he was to attend, or any church he was to preach, it was duly noted in both newspapers.

However, where Turner’s propaganda failed is that it did not factor in the internal characteristics. Turner did not or refused to have knowledge of the psychological terrain. The propagandist must know the “sentiments and opinions, the current tendencies and the stereotypes among the public he is trying to reach” (Ellul 34). Turner’s propaganda was very popular in the South. Turner, reflecting after the failed convention wrote in the Voice of Missions, “What under heaven would I want with a national convention of over seven hundred delegates to endorse African emigration, when at least two million of colored people here in the South are ready to start to Africa at any moment, if we had a line of steamers running to and fro” (Black Exodus 193).

Where immigration was not popular was in the North. Many blacks in the North favored staying in America and trying to appeal to whites for justice and equality. Also it must be mentioned that many blacks in the North were “middle-class blacks” and many had made some progress during Reconstruction. Albeit still troubled by racism and prejudice, blacks in the North lived much better than blacks in the South. Redkey notes that “American individualism had begun to bear fruit for them and, despite their belonging to the black caste, they had risen in wealth and education above the masses of plantation workers” (Black Exodus, 30). Blacks in the North felt as if they had more to lose on a risky venture such as emigration whereas Southern blacks thought, “it could not be worse than it is already for us now.”

Turner also underestimated the strong myths associated with Africa. Many blacks had questions about the “suitability of the Dark Continent.” These questions were largely based upon “ignorance, misinformation, and the grim accounts of some disillusioned travelers.” There was major concern about the climate and the unbearable heat, which many believed, led to incurable fevers and all kinds of diseases. It also did not help Turner’s case when some emigrants returned from Africa with horror stories of death and disease and talked about the many swamps an inhabitable land in Africa. Even white people, who were concerned that a ready labor supply was all going to emigrate to Africa, started spreading rumors about Africa.

Though Turner grounded his propaganda in current and contemporary events, it struggled to move people to action for two main reasons. For blacks in the North, the myths about Africa and the love for what America could be was just too strong. For blacks in the South, they were more ready to go but lacked the necessary funds. Therefore, the emigration campaign cannot be considered as being timely because both blacks in the North and South did not respond in timely action.

However, what really sabotaged Turner’s plan was the counter-propaganda associated with his emigration campaign. As much as Turner spoke and wrote for emigration there were others who were speaking and writing against emigration. Counter-propaganda had always been associated with Turner’s emigration plan, but by 1883 “black churchmen and secular leaders who were optimistic about the United States began to attack Turner’s emigration schemes in the AME’s weekly Christian Recorder”, the most “influential black newspaper in the land” (Black Exodus 30-31)

The Christian Recorder published much opposition to emigration plans. Many of the Recorder’s writers felt that emigration was too great a price to pay for social equality. Also some made the argument that blacks are Americans and have no affinity towards Africa. Frederick Douglass, who earlier Turner called that “great prince of Negroes,” reminded Recorder readers that blacks had “been in America for 250 years” and owed nothing to Africa. Douglass believed that America provided the best place for blacks to achieve equality.

Also part of the counter-propaganda was the characterization of southern blacks by northern blacks. Knowing that Turner’s appeals for emigration resonated with southern blacks; some northern blacks started a campaign that elevated their status as people who were “literate” versus the “illiterate” people in the south. Following this logic, Benjamin Tanner, editor of the Recorder could write that since he “knew the thoughts of those Negroes who could read and write, what one thoughtful man among us writes outweighs in value the whole Niagara of eloquence common to our people [who] talk in the vein that we know our hearers desire us to talk.” He was also critical of Turner for hearing only what he wanted to hear and not really listening to his own people. (Black Exodus 33).

Tanner also pointed out that while Turner was espousing leaving America, many people were coming to America to fulfill dreams in the land of opportunity. Tanner also reminded his readers that even Africans who come to America to study usually stay in America after their studies are completed. Tanner wrote in the Recorder, “The idea of a people leaving a country like America to go anywhere to better their condition…is like running from the sun for both light and heat” (Black Exodus 33-34).

Turner addressed his critics at every turn. However, as the propaganda war escalated, Turner was out-propagandized. Along with stinging critiques of his emigrations plans also came lies, innuendo, and gossip about Turner and his association with the American Colonization Society; a group that many blacks believed was racist. Turner propaganda worked in the South, where times were extremely hard and anything had to be better than what many blacks were experiencing already. However, in the North, where many blacks achieve a level of comfort and middle-class status, Turner’s propaganda fell on deaf ears.

Conclusion

There very well may be other reasons for Turner’s failed emigration plans; his lack of tact with blacks that disagreed with him, his black nationalistic attitude, and lack of funds. Nevertheless, when Turner decided to promote the last leg of his emigration plan, he decided to call a national convention. So why here I began to wonder why would Turner call for a convention to promote the last leg of his emigration campaign?

Well, first maybe Turner saw the conventions as space and place to share innovative ideas. Turner knew that emigration was a tough sell, but it had always been at the conventions that these types of non-traditional ideas were lifted, debated on and sometimes celebrated. Second maybe it was because the colored conventions were ran and operated by black folk. The convention movement demonstrated to Turner and others that blacks could organize and produce good and effective work if given a chance.

However, finally, the reason why Turner harken back to the convention movement was because while others saw brighter days ahead for African Americans, Turner saw some else. Turner saw that despite the rhetoric of racial uplift, despite numerous announcements of how much success African Americans achieved, black folks still suffered in mass numbers. Lynchings went unabated, violence was a daily threat to any African American, and many black folk lived under the threat of terror every single day. It was at this time that Turner suggested what black folk needed was a national convention to come, discuss and talk about what does it mean to live unprotected randomly facing violence every single day of your life?

And as we struggle in 2015 seeing the constant barrage of black bodies lying on asphalts and pavements all across this country; in lieu of black bodies filling up our jails and prisons under the New Jim and Jane Crow system of justice, maybe it’s time for us to revisit the convention movement.

Thank You.