As a curious little brown girl growing up in the Northeast, I vividly remember the horror I felt when I learned about the church bombing in Birmingham, Alabama on September 15, 1963. I remain blessed that my mother saw fit to send my brother and I to the local African American Cultural Center, where we received the “Black history” information we were not receiving in our parochial school curriculum. At ten years old, I could not believe that someone would intentionally bomb a church, and four little Black girls—Addie Mae Collins, Cynthia Wesley, C. Denise McNair and Carole Robertson—perished. This was one my first experiences of race hatred, of race terrorism, and my childhood was violated with the knowledge that there are people in the world who will hurt, maim, and kill you because of what my mother called “your outer packaging.”

I vowed never to forget these girls, little girls who looked like me and died at the same age I was at the time I was taught about their deaths. I have thought about them a lot in the wake of the recent events in Charleston, South Carolina. Once again, my mind is filled by images of Black people in a church under terrorist assault. And that is not the only assault that has plagued Black bodies of late: images of pregnant Black women wrestled to the ground, Black teenage girls being violently handled by police, images on repeat of violent Black death caught on camera, I can barely keep up. I am actually afraid to count the number of stories on the news and circulating on social media just in the past month of Black people dying because the actual number might put me over. As a woman of color in ministry, I give myself permission to ask WHERE…IS…GOD? Is that not always the question asked in times like this? How can a God of love allow such heinous acts to occur? For some, the rationale becomes one of divine retribution: that if someone horrible has happened, the inflicted must have brought it on him or her self. Some use this inquiry as evidence that God does not exist, and others simply don’t care about anything that does not impact them directly. And the latter is the trajectory of thought I would like us to consider: that perhaps one reason these events persist is a profound lack of empathy from those not directly impacted. So rather than seeking a Divine proximity check, perhaps the question we should be asking is can you consider yourself a Christian if you are not invested in your neighbor?

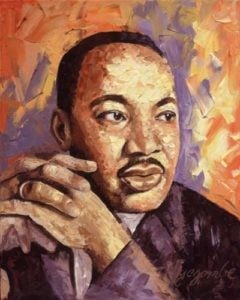

The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., whose own mother was killed in church, was heavily invested in the concept of personalism. The ontological point of departure for this moral philosophy is the value of the human person. In other words, personalism is a philosophical worldview that suggests that the whole of humanity carries with it a basic respect, a value that merits respect. Much of this thought influenced King’s “world house” and “beloved community” appeals during the Civil Rights Movement. King believed the beloved community was not one of a utopian Garden of Eden reboot, but rather the idea of a multicultural community working together to eliminate poverty, racism and militarism. King’s ideals are helpful in understanding what I believe is missing from contemporary racial discourse: a deliberate stand by allies. This is not a condemnation of all; of course there are allies across the country working toward a more tolerant society.

However, I cannot help but wonder who will stand up and condemn hate speech like that used by the alleged shooter, Dylann Roof, who walked into Emmanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina and according to witnesses exclaimed: “you rape our women and you are taking over our country” before opening fire on Bible study attendees. His comment is straight out of the white supremacy handbook, a rhetoric that has been repeating on a loop since the film “Birth of a Nation.” White supremacy is based in fear and is a principality and a power in a high place. More importantly, it is not just a struggle for black and brown people, it is a struggle for ALL people. Where are the allies decrying White supremacist rhetoric? Is it not clear that imagined fear is FATAL? Can you be a Christian and show no concern that this false narrative is a common denominator in recent acts of violence against black and brown skin?

If Jesus were to teach the Parable of the Good Samaritan today, He might title it differently. I am convinced that the illustration of a “good” Samaritan to His audience two thousand plus years ago was meant to make the first hearers uncomfortable, to force them to wrestle with what cultural differences mean when someone needs help when a persistent threat, the Jericho road, has claimed another victim. Today Jesus might teach tolerance of others using a title like “The Good Klansman” and the Jericho road is white supremacy. I’ll just leave that right there for a minute. What if there is a reckoning for a lack of empathy with Black pain in particular and all senseless murder in general? In any event, if loving others as ourselves is the clarion Christian call, and if the world only recognizes Jesus’ followers using the love shown one to another as a marker, silence on white supremacy may render many of us to fans of Jesus. Not followers. The question is not one of where God is. The question is whether or not you can remain unmoved when a significant portion of your Christian brothers and sisters of color are under terrorist attack, or how you can remain silent when you hear white supremacist rhetoric in any of your shared spaces.

Tell us what you think

Kimberly Peeler-Ringer is a contributor for R3