On Tuesday, April 12 the American Inns of Court in Memphis, Tennessee invited me and other members of the Lynching Sites Project to come and share the story of the lynching of Ell Persons. Attorney Carla Peacher-Ryan and Dr. Tom Carlson promoted the work we do in the recovering of lynching sites in Shelby County, while Dr. Margaret Vandiver discussed the broader implications of the Persons lynching. I had the task of giving a speech detailing Persons lynching and the aftermath. *Special thanks to Judge Jennie Davidson Latta for arranging our visit. My speech is below.

On Tuesday, April 12 the American Inns of Court in Memphis, Tennessee invited me and other members of the Lynching Sites Project to come and share the story of the lynching of Ell Persons. Attorney Carla Peacher-Ryan and Dr. Tom Carlson promoted the work we do in the recovering of lynching sites in Shelby County, while Dr. Margaret Vandiver discussed the broader implications of the Persons lynching. I had the task of giving a speech detailing Persons lynching and the aftermath. *Special thanks to Judge Jennie Davidson Latta for arranging our visit. My speech is below.

On May 2, 1917, after a two day search into the whereabouts of 15 year old Antoinette Rappel, a search team found her decapitated body lying in the woods. The News Scimitar described the scene as such: “Lying on its back, with arms and limbs outstretched, and with clothing torn and disheveled, the headless trunk of Miss Rappal’s [sic] body was found. Near her right foot was the severed head, its golden tresses clotted and tangled with blood. The wide-staring blue eyes bore a frozen expression of horror.” A doctor concluded that “Miss Rappel had been sexually assaulted, but could not determine whether this happened before or after her death and “scratches and bruises on her shoulders and arms seemed to indicate that she had resisted her attacker.”[1]

According to newspaper accounts, detectives initially suspected that a white man killed Rappel. Her bicycle “had been discovered leaning against a tree about one hundred feet from the road, with her belongings still in the basket. This seemed to indicate that she had not been forcibly seized and dragged away from the road because detectives surmised that she would not have “left the road” to go to a black man but might have “followed a white man she knew.” Even a respected doctor at the time, Lee A. Stone, believed that a “white man committed this terrible crime.” Dr. Lee went so far as to reason that the man who killed Rappel was a necrophiliac who killed her before sexually abusing her.”[2]

Also according to newspaper accounts, on the evening of the day the  killer committed the crime, there was a story about a white man, wearing a “light suit” acting “strangely” while at a train depot in Woodstock. The significance of this according to Margaret Vandiver, who devotes an entire chapter to the lynching of Persons in her book Lethal Punishment: Lynchings and Legal Executions in the South, is that a white vest or coat had been found near the place of the murder. Even a week after the crime, a white man, who claimed that the handkerchief found at the scene was his because he and his friends were in the area near the time of the murder, claimed to have seen a white man, “bareheaded and apparently much excited,” leave the underbrush and walk away quickly down the road. According to Vandiver, “there is (was) no indication that the police ever considered this man as a suspect or asked for confirmation of his account from his friends.”[3]

killer committed the crime, there was a story about a white man, wearing a “light suit” acting “strangely” while at a train depot in Woodstock. The significance of this according to Margaret Vandiver, who devotes an entire chapter to the lynching of Persons in her book Lethal Punishment: Lynchings and Legal Executions in the South, is that a white vest or coat had been found near the place of the murder. Even a week after the crime, a white man, who claimed that the handkerchief found at the scene was his because he and his friends were in the area near the time of the murder, claimed to have seen a white man, “bareheaded and apparently much excited,” leave the underbrush and walk away quickly down the road. According to Vandiver, “there is (was) no indication that the police ever considered this man as a suspect or asked for confirmation of his account from his friends.”[3]

Now with these suspects, one may wonder how Ell Persons became not only suspect, but also the one charged with this horrible crime. Well, a white man by the name of E.J. Brooks told Sheriff Tate that Persons had “frightened his wife” by saying to her that he had dreams about her. According to reports, Brooks told Sheriff Tate that “My first impulse was to put a hole in the fiend, but rather than cause any trouble, I fired [him]…. I wish now I had killed him.” Therefore, despite having other suspects to investigate and interview, after the word of Brooks, Sheriff Tate arrested Persons. The statement from Brooks apparently had an effect on Sheriff Tate. In arresting Persons, Tate remarked that Persons’ dream “was charged with possibilities. It showed that Persons was a Negro capable of committing a crime such as the Rappel murder. It gave us the first inkling of his brutish proclivities and we lost no time taking him into custody.” [4]

After Sheriff Tate released Persons twice, once to follow Persons to see if he would lead him to the murder scene, (which he did not do), Tate arrested him for the final time on May 6, 1917. It was at this time that Persons “confessed” to the crime. The confession however, was not without its own problems. The Memphis Press reported that the “sheriff, with [detectives] Brunner and Hoyle, past masters in the art of the third degree, coaxed, cajoled, beat, whipped, threatened, pleaded with the Negro to no avail. But finally, at the psychological moment, when the black man’s resistance was worn to the breaking point, Detective Hoyle pointed suddenly to the Negro’s shoes. “There’s blood on your shoes now!” The city chemist can tell if it is human blood. Take off those shoes.” About an hour passed and when Hoyle returned with the shoes, he told Person “it’s human blood.” It was at this moment that Person supposedly confessed. After detective Hoyle confronted Persons with the “shoe evidence,” the News Scimitar reported that Persons declared, “I’ll tell you, boss…I killed her, but I want to be sent to the asylum, because I am crazy. However, another article in the same paper on the same day reported that the chemist found no blood on Persons’ shoes or pants.[5]

A more detailed confession appeared in the Commercial Appeal. Persons told reporters that I was in the bottom cutting cane for pea sticks when I saw the little girl come down from the road leading her wheel. She leaned the wheel against a tree and 6 then stepped back. I sneaked up behind her and brought the ax down on her head. The first blow did not knock her down, and she turned and fought me…. Then … I split open her head with another blow. She fell. In fear that she would recover and tell I then chopped off her head and threw it into the underbrush. Then I dragged the body 30 to forty feet back into the bushes.

After the press made Persons’ confession public, Sheriff Tate knew that a lynching was a strong possibility. To stop that from happening, he sent Persons to Nashville to await trial there. While mobs searched high and low for Person, Judge Puryear exhumed Rappel’s body. The reason for this was so that her eyes could be photograph because of the belief that the last image seen would produce an imprint in the retinas. Despite ophthalmologists offering a resolution stating that the eye could not retain such an image, the Commercial Appeal reported that the procedure revealed “the outlines of a full-faced, large featured man” visible when the photograph was viewed under a microscope. The News Scimitar asserted that the police said that the image was “a likeness of Persons.” [6]

Judge Puryear scheduled Persons arraignment and trial on Friday, May 25, 1917. He also appointed two lawyers who tried their best to get out of the assignment—L J. Monteverde and Robert H. Prescott. The former argued that “defending Persons “would require him to surrender his feelings as a man in obedience to his duties as an officer of the court,” while the latter maintained that he had “provided evidence in the case to the district attorney and thus had a conflict.” By this time, Persons was on his way back to Memphis.

Deputies R.B. Wilroy and G.E. Thomas removed Persons from his Nashville jail cell at 3:00am. Fearing the mob, the plan was to take Persons through Birmingham, through Mississippi and then to Memphis. However, a mob of several hundred men caught wind of the plan and met the train as it arrived in Potts Camp, Mississippi. Sadly, there was no resistance offered from the deputies and they handed Persons to the angry mob. Vandiver suggested that the abduction was carefully planned and organized as echoed by the Commercial Appeal’s account of the abduction. They commented on the “perfect order” maintained by the leaders of the mob, whom the paper referred to as the “committee which had planned and executed the capture.” [7]

On Tuesday morning, the Commercial Appeal ran a front page story that said it all: “MOB CAPTURES SLAYER OF THE RAPPEL GIRL Ell Persons to Be Lynched Near Scene of Murder MAY RESORT TO BURNING.” According to Vandiver, despite the Commercial Appeal and other media outlets reporting that a lynching was sure to happen, there was no effort among law enforcement to take Persons back into custody. In fact, police may have been spectators and participants. According to Commercial Appeal reporter Boyce House, who wrote about the lynching in his memoir wrote that he went a “with four policemen in plain clothes to the scene (they had no intention of stopping the lynching but wanted to see it).[8]

House described the scene of the lynching this way: No effort was made at disguise, not even so much as a hat-brim pulled low or an overcoat collar turned up. Many rifles and shotguns could be seen. Farmers and workers were numerous. There were many others who were businessmen, professional men and clerical workers, probably there as sight-seers rather than as participants, though no doubt in sympathy with the business at hand.[9]

In addition, House also reported that one of the officers that came with him served as the “Master of Ceremonies for the lynching; “raising his hand like the master of ceremonies at a prize fight club.” The Commercial Appeal reported that this “MC” commanded silence and “announced that the mother of the murdered girl desired to make a statement. The crowd surged closer to catch her words, which proved to be audible for a distance of about 50 feet. “I want to thank all my friends who have worked so hard in my behalf,” she said. “Let the negro suffer as my little girl suffered, only 10 times worse.” “We’ll burn him,” the crowd yelled. “Yes, bum him on the spot where he killed my little girl.”

And burned him they did. Instead of hanging him, they decided to take him down and they tied him to a large log. Someone doused him with gallons of gasoline and after a minister by the name of Brother Royal decided that Persons wasn’t someone who they people should pray for or for Persons to pray himself, they set the fire to his body.

According to newspaper reports, the death was instantaneous, but the News Scimitar wrote that he was “slowly roasted to death” and he made no outcry. However, the News Scimitar added this caveat for history: While the fire, starting at [Persons’] feet, crept slowly toward his face a 10 year old negro boy was placed on the other end of the log. “Take a good look, boy,” someone told him. “We want you to remember this the longest day you live. This is what happens to niggers who molest white women.”[10]

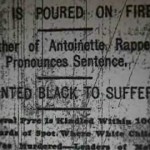

If that wasn’t bad enough, after his death, Persons body was mutilated. Persons’ heart was cut out of his body while the body still burned; others cut off his ears and another cut off his head, while yet others “rushed for souvenirs.” People continued arriving at the scene after the lynching and thousands came out during the day, many seeking souvenirs. After the lynching, three men threw Persons head and foot from a car at a group of African Americans at the corner of Beale and Rayburn Boulevard, yelling as they did it, “Take this with our compliments.” The headlines of the Commercial Appeal on Wednesday, May 23 read: THOUSANDS CHEERED WHEN NEGRO BURNED Ell Persons Pays Death Penalty for Killing Girl OIL IS POURED ON FIRE WANTED BLACK TO SUFFER

If that wasn’t bad enough, after his death, Persons body was mutilated. Persons’ heart was cut out of his body while the body still burned; others cut off his ears and another cut off his head, while yet others “rushed for souvenirs.” People continued arriving at the scene after the lynching and thousands came out during the day, many seeking souvenirs. After the lynching, three men threw Persons head and foot from a car at a group of African Americans at the corner of Beale and Rayburn Boulevard, yelling as they did it, “Take this with our compliments.” The headlines of the Commercial Appeal on Wednesday, May 23 read: THOUSANDS CHEERED WHEN NEGRO BURNED Ell Persons Pays Death Penalty for Killing Girl OIL IS POURED ON FIRE WANTED BLACK TO SUFFER

After the lynching, many white Memphians went on about their business thinking that what had happened was a right and moral thing to do. However, despite the belief that Persons was guilty of the crime, some expressed remorse and shame. The Jewish brotherhood adopted a resolution that read in part

In all the history of crime there was never any act of murder and outrage more fiendish and devilish in its contrivance than that committed by the negro, Ell Persons, against the young girl, Antoinette Rappel….The brute who committed the act deserved a hundred deaths…. But…[w]e are face to face with the old question of whether society disorganized can better accomplish results than the organized forces of law…. Men cannot give the law temporary paralysis and then expect it to resume a vigor in protecting all of the rights of all of the people….After a criminal is in the hands of the sworn officers of the state, and when there are juries and judges and prosecuting attorneys and electric chairs ready to act, willing to act, there can be no excuse for refusing to let them act.[11]

After helping stoke the passions that led to the creation of the mob and maybe reflecting on what happened, the editor of the Memphis Press wrote

We burned a Negro at the stake yesterday. Let us underscore the word “WE.” So if we are proud of it, let us be proud of it together. If we are ashamed of it, let us be ashamed of it together….It would be as senseless to put all the blame on the man who made the brimstone for the match that ignited the funeral pyre as it would to put it all upon the men who participated in the lynching itself. Public opinion burned Ell Person–the minister of the gospel, the lawyer, the doctor, the newspaper editor, the man who talks to others on the street corner, or the street car–he shared in it, that is, he did, unless he protested, and there were few protests. The majority kept silent, and silence gives consent.[12]

The News Scimitar also had a moment of reflection

The murder of Miss Antoinette Rappel was an atrocious crime, with exceptionally revolting details. A certain section of a universally outraged public sentiment determined that the punishment fixed by law was insufficient in these circumstances, and therefore the execution of the criminal was outside the written statute. The manner and form of the execution had no relation to the color of Ell Persons’ skin. Under a similar state of facts we may well believe a white man would have met the same fate. There is no race war in Shelby county. It is fortunate that the guilt of this murderer was certain, and that the avenging citizens who meted punishment stayed their hands in the case of other suspects, about whose participation in the crime there is cause for grave doubts. A lynching, regardless of provocation, brings the written law into contempt, and under some circumstances makes a farce of constituted government. No man can have contempt for one law without having some degree of contempt for other laws. The effects of a lynching are certain to be brutalizing, as some details of the event in Shelby County prove. Vengeance for a specific outrage having been satisfied, let “invisible government” disappear, and let this community now return to government by its legal authorities.[13]

Finally, a delegation of twenty-five pastors met for two hours in a closed door session at the Chamber of Commerce. Led by Rev. T. E. Sharp, president of the Protestant Pastors’ Association, the delegation included six African Americans pastors who, according to reports remained silent during the meeting. From the meeting they offered the following resolution

We, clergymen of the city of Memphis, met in solemn assembly, do hereby resolve that we, as clergymen and citizens, confess our dereliction of duty in not having warned an inflamed public opinion against mob violence when it was apparent to every reader of the newspapers that preparations had been made for lynching the brute who had committed an unspeakable crime. We furthermore resolve that it should be brought home also to the consciences of other representatives, men and leaders of this community, that they, too, failed to do their duty; that it appears also that the constituted servants of the law had failed, by subservience to the will of the mob, and by inadequate preparations to resist their anarchic designs[,] to take the proper measures to defend the dignity and majesty of the law an our civilization; that the conscience of the community had been dulled to the apprehension of the enormity of such lynchings and their accompanying degeneracies. We call upon the citizens of this community to put away the false theory that lynchings are deterrents to crime, to realize that mob violence saps the foundation of democracy, law and civilization; that we cannot rear our children in safety if we set the example of law breaking and give it our sanction. We appeal for the continued extension of mental, moral, industrial, and spiritual education of the Negro as the most effective deterrents of crime. We appeal to our fellow citizens to stand together as one[14]

African Americans also responded to Persons lynching. A small group of African Americans organized and formed a chapter of the NAACP. The National Negro Medical Association moved its convention from Memphis because of the person lynching. Blacks held large demonstrations in New York protesting the lynching. Even the NAACP Field Secretary James Weldon Johnson came to Memphis to investigate the lynching. He spent ten days in Memphis talking with “the sheriff, with newspaper men, with a few white citizens, and many colored ones” and reading through local newspaper coverage of events.” Johnson concluded there was no evidence that Persons had killed Antoinette Rappel.

As recorded in Vandiver’s book about the lynching

Robert R. Church took Johnson to the site of the lynching, where he found that “all the paraphernalia of the unspeakable orgy were still there. . . . At the base of this iron rail to which Ell Person had been chained the earth was still black and charred; at its top, placed there to mark the spot, there floated an American flag.” Writing later in his memoir Along This Way, James Weldon Johnson reflected upon his trip to the scene of Persons’ death and wrote that “the truth flashed over me that in large measure the race question involves the saving of black America’s body and white America’s soul.”[15]

The lynching of Ell Persons leaves us with more questions than answers. What was the role of law enforcement, the courts, and the press? Where were the clergy in all if this? What are we to make of Persons confession? And what motivated the mob to play judge, jury and executioner? These and other questions we hope to touch in our discussion period. However, if we are to move together to carve out a blessed future, we must acknowledge our tortured past and have the courage to admit and learn from our mistakes.

Thank You

[1] Margaret Vandiver. Lethal Punishment: Lynchings and Legal Executions in the South. Rutgers University Press. New Brunswick, New Jersey, 2005 p. 121

[2] Vandiver, 121

[3] Vandiver, 121-122

[4] Vandiver, 122

[5] Quoted in “The Memphis Lynching Log” by Jennie Latta. NP, 7-8 ; Vandiver, 123

[6] Vandiver, 124

[7] Vandiver, 126

[8] Vandiver, 127

[9] Vandiver, 127

[10] Vandiver, 129

[11] Latta, 16

[12] Latta, 16-17

[13] Latta, 17

[14] Latta, 19

[15] Vandiver, 136

Donate to the Work of R3

Like the work we do at Rhetoric Race and Religion? Please consider helping us continue to do this work. All donations are tax-deductible through Gifts of Life Ministries/G’Life Outreach, a 501(c)(3) tax exempt organization, and our fiscal sponsor. Any donation helps. Just click here to support our work.