Answering a Question about the Trinity: Is “Social Trinitarianism” a Heresy?

I am informed that some evangelical (and perhaps other) theologians are again labeling social trinitarianism a heresy. To put it bluntly and “up front,” this is nonsense. But, as you should be aware, there are conservative theologians who specialize in identifying heresies. They seem never to be satisfied; three is always another heresy lurking just around a corner. They get “points” from colleagues and “higher ups” (in their denominations and organizations) for identifying heresies where they have not been noticed before.

So what is “social trinitarianism?” Well, the answer to that is not so simple. It depends much on whom you ask. I have studied the concept for many years and no two explanations of it are identical.

While I was in seminary, I read widely and deeply in theology—far beyond what was required. One of the theologians I encountered was Leonard Hodgson (1889-1969) who taught theology at Oxford University. One of his books, recommended to me by my seminary faculty advisor Samuel Mikolaski (who earned his Oxford degree under Hodgson) was The Doctrine of the Trinity (1944). I liked it, a lot. Hodgson was developing and defending a version of the social Trinity and I was convinced that it was (and is) better than alternatives such as the so-called “psychological model” of the Trinity that goes back at least to Augustine in the fourth and fifth centuries. (I also read a book that promoted and defending that view of the Trinity by theologian Claude Welch entitled In This Name: The Doctrine of the Trinity in Contemporary Theology (1952).

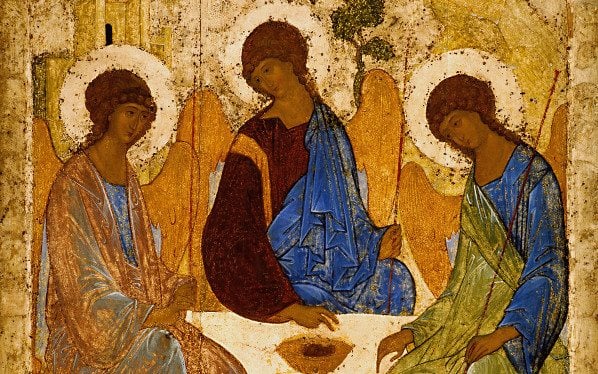

In brief, social trinitarianism, or belief in the social model of the Trinity, is the idea that Father, Son and Holy Spirit are three distinct persons bound together eternally and equally by one divine nature or substance and by perfect love. Something like this was promoted and defended by the Cappadocian Fathers of the fourth century—Basil the Great, Gregory of Nyssa, and Gregory Nazianzus.

Why the emphasis on three distinct persons, the starting point of thinking about the Trinity for social trinitarians? Simply because the Bible, especially the New Testament, requires it. Think of all the gospel narratives in which Father, Son and Holy Spirit are clearly not one person—such as Jesus’s baptism. But I don’t have time or space to go into every supporting biblical passage. You can read these for yourself if you are interested enough to read a good book about the social Trinity.

*Sidebar: The opinions expressed here are my own (or those of the guest writer); I do not speak for any other person, group or organization; nor do I imply that the opinions expressed here reflect those of any other person, group or organization unless I say so specifically. Before commenting read the entire post and the “Note to commenters” at its end.*

I was already convinced of social trinitarianism when I heard about and then attended a high-level theological conference held at Marquette University in Milwaukee, Wisconsin in 1988. The title of the conference was “Trinity, Incarnation, and Atonement.” It was convened, as I recall, by two Calvin College and Seminary theologians, professors, named Ronald Feenstra and Cornelius Plantinga. I drove down to Milwaukee for the conference together with my Bethel College colleagues, philosopher-theologian Mel Steward. I don’t remember all the presenters or their papers, but the focus of the conference was to explore the concept of the social Trinity and kenotic Christology. (The two tend to go together.) The conference resulted in an edited volume entitled Trinity, Incarnation, and Atonement: Philosophical and Theological (University of Notre Dame Press, 1990.) I used to own the book, but like so many of my books, it “walked away.” I haven’t seen it in years. But I remember that it contained some, if not all, of the papers read at the conference.

For years I have recommended to my students a popular essay that I assume arose out of the conference: “The Perfect Family: Our Model for Life Together Is Found in the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit” by Cornelius Plantinga (Christianity Today, March 4, 1988). For non-theologians, Plantinga lays out the social Trinity very well. I highly recommend it if you can get a copy. With Christianity Today’s and Plantinga’s permission, I made copies of the article and handed it out to my students. It is the finest exposition of the doctrine of the Trinity from a social perspective I have read—for non-theologians.

Social trinitarianism is really the only alternative to an Augustinian view of the Trinity that begins with the oneness of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, and struggles to explain how they can be three distinct persons such as is portrayed in the New Testament and the early Greek church fathers. The Augustinian view of the Trinity is sometimes called the “psychological analogy” because Augustine used psychological concepts (of his time) such as “memory,” “understanding,” and “will” to depict and describe the threeness of God. But that means the best analogy for the Trinity is one human person with three dimensions or aspects. It would be very difficult to reconcile that with New Testament narratives about Father, Son and Holy Spirit. For example, in the Gospel of John Jesus told his disciples that he would send them “another comforter” or “another advocate”—the Holy Spirit. He didn’t say he would return in some ethereal form.

The danger of the social Trinity concept is, of course, tritheism—belief in three Gods. Therefore, the Greek church fathers emphasized the “perichoresis” of the three persons (“hypostases”)—their interpenetration. And they came up with the principle “opera trinitaris ad extra indivisa sunt” (Latin translation which in English means “all acts or operations of the Trinity are indivisible.” But the danger of the psychological model of the Trinity is modalism and I don’t see anyway to escape it insofar as the Trinity is compared with a single, individual human person (e.g., modern theologian Hastings Rashdall’s analogy of the Trinity using President Teddy Roosevelt’s three roles as father, president and rough rider).

The inner “workings” of the Trinity are mysterious to us; we cannot really know them. But, of the two major theological (not Sunday School) analogies, I prefer the social analogy or model of the Trinity—as expressed, for example, by Cornelius Plantinga in his Christianity Today article.

*Note to commenters: This blog is not a discussion board; please respond with a question or comment only to me. If you do not share my evangelical Christian perspective (very broadly defined), feel free to ask a question for clarification, but know that this is not a space for debating incommensurate perspectives/worldviews. In any case, know that there is no guarantee that your question or comment will be posted by the moderator or answered by the writer. If you hope for your question or comment to appear here and be answered or responded to, make sure it is civil, respectful, and “on topic.” Do not comment if you have not read the entire post and do not misrepresent what it says. Keep any comment (including questions) to minimal length; do not post essays, sermons or testimonies here. Do not post links to internet sites here. This is a space for expressions of the blogger’s (or guest writers’) opinions and constructive dialogue among evangelical Christians (very broadly defined).