Yesterday I posted here about my years-long involvements in Catholic-Evangelical dialogues. This past weekend I participated in another one. I was very glad to be invited and enjoyed all of it and benefited from it. I applaud those who provide the impetus for it and organize it.

Now, looking back over this one and many others I’ve participated in, I’d like to share some ideas about how to improve them.

First, right off the bat, at the very beginning of every weekend session and in the printed material given to participants, define “evangelical.” The term is so broad as to be useless unless it is defined by the person using it. When I hear (or read) “evangelical” from someone I don’t know well, I have no idea what they mean unless they follow it with at least a brief paragraph defining their use of the term.

As I wrote in my The Westminster Handbook to Evangelical Theology there are at least six distinct meanings of “evangelical.” They include the journalistic meaning (politically conservative Christian), the European meaning (Protestant) and the post-WW2 meaning of a post-fundamentalist but basically theologically conservative Protestant who also believes authentic Christianity includes a decision for Christ and a personal relationship with Jesus.

“Evangelical” in Braaten’s and Jenson’s Center for Catholic and Evangelical Theology meant “Protestant.” The same was true in the Munich dialogues led by Pannenberg. However, I have the sense that it means something more specific than just Protestant in the on-going colloquium a part of which I attended and participated in this past weekend. A leading evangelical seminary president was the moderator. One of the organizers is a well-known evangelical theologian who teaches at a well-known evangelical school in Canada. But it was unclear to me what the organizers mean by “evangelical” beyond just “Protestant.” I’m quite sure they mean something more specific, but what remains unclear (at least to me). (Some of the Protestant participants are people I have heard distance themselves from the concept “evangelical” in the past.)

Second, invite more than just Lutheran and Reformed theologians to represent the evangelical side of the dialogue. Braaten and Jenson did invite a denominational diverse group of Protestants to their ecumenical dialogues, but most (I would say I was the only exception) were either some kind of Lutheran or some kind of Reformed in terms of theological orientation. The same seemed to me to be the case in this past weekend’s events. I did see a couple of folks there that would probably not identify as either Lutheran or Reformed (e.g., Stanley Hauerwas and some of his students and proteges). However, as the discussions unfolded it seemed that most of the participants were speaking either as Catholics or Reformed Protestants. Occasionally someone spoke up on behalf of a kind of Hauerwasian perspective that can sometimes sound Anabaptist but at other times more Catholic. (I’m still trying to figure out exactly how to describe the Yoderian-Barthian perspective held by Hauerwas and his disciples/followers). My point is, about all these dialogues–where are the Methodists and offshoots of Methodism? Where are the Wesleyan voices? That leads to my third point.

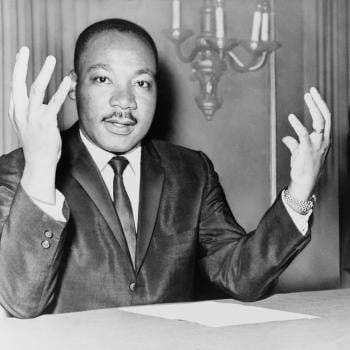

Third, it would be helpful in these dialogues to make sure that the “evangelical” side of the dialogue is represented by more than just magisterial Protestants and especially by some from the Arminian-Wesleyan traditions. We represent a huge portion of evangelicalism and mainline Protestantism and yet our theological perspective seems to get overlooked. Both last year and this year (as in the Braaten-Jenson dialogue events) I had to speak up for Wesley and point out that Wesley is a kind of bridge between magisterial Protestantism (Luther-Calvin-Anglican) and Catholicism insofar as he advocated a salvation that is more than forensic and is truly transformative (inward grace). He believed in deification and sacraments, etc. He also believed in forensic justification but never divorced from inward transformation. It seemed to me that the underlying assumption of all these Catholic-Evangelical dialogues is that the gulf to be overcome is between Catholic and Lutheran-Reformed doctrines of nature and grace and justification. But many evangelicals (including many in the Arminian-Wesleyan traditions) hold a view that combines both nature and grace and forensic and transformative salvation in a way that is neither extrincicist or intrincicist.

Fourth, it would be helpful to tell the presenters to say something about how their papers relate to Catholic-Evangelical differences and possible mutual understanding if not outright agreement. And they should not assume that the non-Catholics in the room are with Luther or Calvin on the issues. The discussions always seem to come down to what Luther would say or what Calvin would say as if they were the only reformers that mattered.

Fifth, it would be helpful strictly to avoid comparing apples to oranges. I have noticed a tendency among the participants in these dialogues to use “evangelical” to refer to American Protestant folk religion and especially overly individualized, pietistic “Jesus and me” Christianity. While that may be true of many grassroots evangelicals, it’s not the historical or prevailing contemporary meaning of evangelical among evangelical theologians. Pitted against that is often the official theology of Catholicism or Catholic scholarship and theological reflection. That’s simply not fair. IF we’re going to ridicule and deride evangelical folk religion, then let’s at least compare it with, say, the folk religion of untutored Catholic lay people and not with the magisterium or Rahner or even Augustine and Aquinas. As you can tell, this tendency irritates me very much.

Sixth, it would be helpful in these events for the Catholic presenters to at least say something good about evangelical Christianity and for the evangelical presenters and participants to stop apologizing for being evangelical and do something other than reach out to the Catholics to enrich our evangelicalism. In all the Catholic-Evangelical dialogues I’ve participated in I’ve noticed a common tendency. It seems to me the Catholic presenters are there to evangelize the evangelicals and the evangelicals are there to learn from the Catholics and appropriate Catholic theology and liturgy and practices to enrich our evangelical way of believing, worshiping and living. This was certainly NOT the case with Hauerwas’s plenary address at this weekend’s dialogue event, but it seemed to me that the one evangelical paper attempted to show how a belief usually associated with Catholic (or Orthodox) theology can be appreciated by evangelicals and enrich us while the Catholic papers dealt with aspects of Catholic theology evangelicals can learn from.

Of course, part of the problem is that Catholics do have a magisterium and a catechism; evangelicals don’t. (We just have people who want to be pope of all evangelicals and books that implicitly pretend to be “the” evangelical catechism such as the new one edited by D. A. Carson and Timothy Keller entitled “The Gospel as Center: Renewing Our Faith and Reforming Our Ministry Practices.”) So it’s always unclear to me to what extent the Catholics in these dialogues CAN appropriate Protestant or evangelical insights. Protestants/evangelicals always can appropriate Catholic insights (depending on their ecclesiastical affiliations, I suppose). So it tends to happen that the evangelicals at these dialogue events seem hungry to soak up Catholic theology while the Catholics seem anxious to convince the evangelicals they need Catholic theology to become respectable.

Seventh, it would be helpful for these dialogue events to focus on issues that really do tend to divide Catholics and evangelicals. This weekend’s topic was Creation. I don’t think there is any evangelical doctrine of creation or even of the relationship between nature and grace. True, the Lutheran and Reformed scholastics tended to treat nature as not open to grace so that grace had to come as sheer miracle totally unanticipated by nature. (This is what was behind the Barth-Brunner debate of the 1930s.) (The idea of the imago dei is involved there. But there is no “evangelical view” of the imago dei.) I think the effort would be better put forth focusing on something like salvation that does tend to divide Catholics and evangelicals (e.g., whether merit is involved). This may have been the theme of last year’s event. I wasn’t an invited participant, so I don’t know.

All-in-all, in spite of these suggestions, I value and enjoy all the dialogues I have participated in. (Up until I was dropped from Braaten’s and Jenson’s dialogue events because I said Baptists would never accept a formal episcopacy.) I just think a few steps could be taken to improve their clarity. I’ll be very blunt here. My impression of the two Catholic papers was that they were written for other Catholics and not for evangelicals. They focused on very fine points of Catholic history and doctrine and, to the best of my interpretation, did not really advance Catholic-evangelical mutual understanding. I didn’t catch anything in either of them that even remotely related to Catholic-evangelical theological disagreement or agreement. Most evangelical theologians are already Augustinian and wide open to at least the 20th century Catholic views of nature and grace (against extrincicism and intrincicism). Both of those papers seemed to be more addressed to the Catholic participants than to the evangelicals in the room. Or they were just informative to both Catholics and evangelicals about Catholic debates and theological points. However, as this was a Catholic-Evangelical dialogue event I assume the Catholic presenters intended the evangelical listeners to learn from them.

Here would be my ideal Catholic-Evangelical dialogue event. Start out by being clear about what “evangelical” means. Invite Catholic scholars who are very knowledgeable about evangelical theology and evangelical scholars who are already knowledgeable about Catholic theology. Instruct everyone to please stick to discussing theology and not bashing folk religion (whether Catholic or evangelical). Ask the presenters to talk about points of possible agreement in spite of historical or apparent contemporary disagreement between Catholic theology and evangelical theology (neither folk religion nor one particular strand of evangelical theology like Reformed). Have respondents to the papers. After a Catholic paper, have an evangelical respondent and vice versa. Then, somewhere during the event, have both a Catholic worship service AND a traditional evangelical worship service for all the participants.