Did Jonathan Edwards Undermine Calvinism?

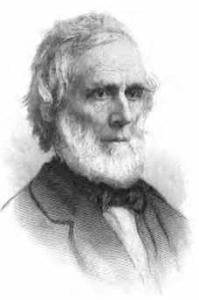

Jonathan Edwards, perhaps the greatest Puritan theologian and a passionate Calvinist, “speaks today” through Calvinist leaders like John Piper even though he has been dead for hundreds of years. Edwards was born in Massachusetts in 1703 (the same year John Wesley was born in England) and died in New Jersey in 1758—just after becoming president of the College of New Jersey now known as Princeton University. He died tragically from a smallpox vaccination. Anyone who knows John Piper, as I do, knows that he reveres Edwards for his great intellect, deep spirituality, and biblical fidelity. Edwards speaks through Piper, not supernaturally, of course, but in the fact that Piper has always praised and parroted Edwards’s ideas even if in his own words.

But did Edwards write something that undermined his own and every classical (as opposed to revisionist) Calvinism? I think so.

Edwards died in 1758 but one of his most important treatises, The Nature of True Virtue, was published posthumously in 1765. “Virtue,” as I will refer to it here, is small, concise, highly philosophical, and difficult for any Christian to disagree with. How to fit it together with other things Edwards wrote and preached is a puzzle. It may even be impossible.

*Sidebar: The opinions expressed here are my own (or those of the guest writer); I do not speak for any other person, group or organization; nor do I imply that the opinions expressed here reflect those of any other person, group or organization unless I say so specifically. Before commenting read the entire post and the “Note to commenters” at its end.*

What Edwards believed about God’s sovereignty is well-known. In treatises such as The End for Which God Created the World and On the Freedom of the Will Edwards attempted to refute any idea that God would be unjust or unwise or unloving to predestine people to hell—even apart from his foreknowledge of their libertarianly free decisions to sin. He didn’t believe in libertarian free will. It is enough to say that Edwards believed and taught that the entire universe is “constituted in each moment by the power of God” and that he meant God creates the whole universe ex nihilo at every moment. This necessarily includes sin; for Edwards nothing at all, even sin and evil, can escape God’s decree and control.

Why has God decreed that certain people, created in his image and likeness, shall necessarily end up in hell for eternity? For God’s glory. According to Edwards (trust me on this or look it up for yourself), God’s whole purpose in creating the universe was to display all of his attributes without prejudice to any. One of God’s attributes is justice and for his justice to be perfectly displayed wrath is necessary and so is hell. Hell, then, and who populates it, is foreordained by God.

Now, all this is well-known to Edwards scholars and students. What is less well-known is Edwards’s teaching about God’s being, beauty, and goodness, virtue, in The Nature of True Virtue. There Edwards expresses very concisely a basic Christian metaphysic in which being itself, God, and goodness itself, God, and virtue itself, God, and beauty itself, God, are inseparably united. And virtue is “benevolence toward being in general.” (The Nature of True Virtue [Ann Arbor, MI: The University of Michigan Press, 1969), 3.)

According to the Edwards of “Virtue,” God is not free to be what he is not; the Edwards of “Virtue” was not a nominalist or voluntarist. Everything Edwards wrote in “Virtue” points to metaphysical realism—the belief that God has an unchangeable nature that governs his actions. Two notable Edwards scholars, Michael McClymond and Gerald McDermott, mention this on p. 545 of their magisterial The Theology of Jonathan Edwards (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2012). About attributes like virtue as benevolence toward being in general they say that “Edwards insisted that these standards to which God conforms are part of God’s own being.” (545)

Now, in order to keep this relatively brief, let me turn to my one main point. Over and over again I have heard Calvinists say “Whatever God does is good just because God does it.” That pops out like a mantra when I or anyone asks them how God can be good and predestine sin and hell. As I have argued here before many times, that makes the word “good” meaningless. And Edwards agreed! I now throw his words back at them.

In “Virtue” Edwards adamantly asserted that God’s own “temper and nature” is virtue meaning love, benevolence, “the cordial consent or union of being to being in general.” And he argued that such benevolence toward being in general did not exclude anyone or anything that has being. Being itself draws forth God’s benevolence. Love of misery in anyone, Edwards argued, is a contradiction of the true nature of reality.

Then comes the “kicker.” On pages 106 and 107 of “Virtue” (the edition specified above), Edwards rejected any idea or argument that “good” can have other meanings than he has identified—namely, benevolence toward being. He specifically labels any notion or argument that “good” in God means something different from “good” in general as “abuse of language.”

“Mankind in general seem to suppose some general standard, or foundation in nature, for an universal consistence in the use of the terms whereby they express moral good and evil; which none can depart from but through error and mistake. This is evidently supposed in all their disputes about right and wrong; and in all endeavors used to prove that any thing is either good or evil, in a moral sense.”

“Abuse of language!” That is how Edwards described “Whatever God does is good just because God does it.”

“Benevolence to being in general” Edwards described as “that consent, propensity and union of heart to being in general, which is immediately exercised in a general good will.” (3)

I ask: How can God be truly virtuous, truly good in a meaningful way, and foreordain the fall of humanity into sin and certain individuals to eternal torment in hell? It is impossible to reconcile Edwards’s account of God and virtue and “goodness” with what he believed as a Calvinist about God’s sovereignty with regard to reprobation.

*Note to commenters: This blog is not a discussion board; please respond with a question or comment only to me. If you do not share my evangelical Christian perspective (very broadly defined), feel free to ask a question for clarification, but know that this is not a space for debating incommensurate perspectives/worldviews. In any case, know that there is no guarantee that your question or comment will be posted by the moderator or answered by the writer. If you hope for your question or comment to appear here and be answered or responded to, make sure it is civil, respectful, and “on topic.” Do not comment if you have not read the entire post and do not misrepresent what it says. Keep any comment (including questions) to minimal length; do not post essays, sermons or testimonies here. Do not post links to internet sites here. This is a space for expressions of the blogger’s (or guest writers’) opinions and constructive dialogue among evangelical Christians (very broadly defined).