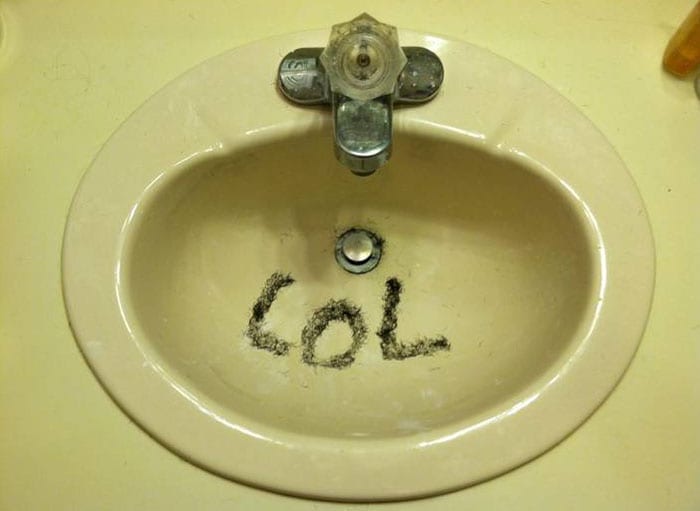

I went into the guest bathroom this morning, just this morning, and found wiry black hair in the sink. One of my grandsons left it. I have two biracial grandsons, so I can’t say which one left it. It didn’t bother me; it never does any more.

Still, it was a mild PTSD moment, shoving my memories back to college, back to Wayland, my black college roommate and his wiry hair, and our arguments about cleaning the sink and how some days I still miss him terribly. That’s the way it is with grief. After the shock of death, grief eventually settles down to become a solitary stab of unexpected memory. That’s what it was this morning.

Wayland died in 1997. The official obituary reported a heart attack; a friend to us both revealed it was AIDS. I guess it could be both but, admittedly, AIDS wouldn’t be a surprise. I knew he was gay. He was 46 at his death.

We had been college room mat es in the late 1960s. For some impossible reason, other than being that hair in the sink looks gross, his hair left in the sink especially seemed gross. It threatened to become a real racial thing for me.

es in the late 1960s. For some impossible reason, other than being that hair in the sink looks gross, his hair left in the sink especially seemed gross. It threatened to become a real racial thing for me.

But since we were the same size and shared a coincident taste in clothing, which expanded our wardrobe possibilities, especially mine, I kept my mouth mostly shut. Then, a memorable day, it got too much for me. I complained – irrationally, I remember him describing it; loudly, I will concede. But to my complete bewilderment, he told me that my stringy brown hair left in the sink made him gag. Gag, he said, my hair made him gag. And he said I was being irrational?

We had to find a compromise. We would clean up after ourselves; no hair in the sink became our rule. I told this story to a friend and she did not know which was more remarkable: That hair could become racialized or that two male college juniors would ever bother cleaning up anything.

He become an Episcopal priest in 1976. I wasn’t kind to him when he told me he was entering seminary, two years after college. I was still in my atheist days and warned him about throwing his life away on stuff and nonsense. He made an anatomically impossible suggestion as to what I might do with myself, and went to seminary anyway.

Naturally, the first sermon I ever preached in a real church was in his Episcopal parish, the same year he was ordained. I wasn’t supposed to be preaching anywhere as a Lutheran first-year seminarian, but he promised not to tell my seminary if I promised not to tell his bishop. It worked. He was very smug about me stumbling into faith.

I remember those years, our exchanges of correspondence and the few times we managed to visit after college, and the inevitable clashes we indulged on the topic of Republicans vs. Democrats, and our experiences of race and racial differences. But of all the things we discussed, sexuality was never part of it. We were friends. Really, what else mattered?

When I heard he died of AIDS my reaction was blunt, how could you have been so stupid, so resolutely careless? Twenty-two years on and when I think of him, I still ask it.

I was then serving a Lutheran parish in a small town in east central Missouri when he died. I was also preparing to attend an AIDS funeral for the son of one of my parishioners. The funeral was to be in Kansas City and the graveside committal was to be at my parish.

The young man had engaged in unprotected sex with a man who – contrary to Missouri law – deliberately withheld disclosure of his HIV status. The offender was arrested and convicted of a Class B felony. The son of my parishioner contracted AIDS and died within two years of that encounter.

When word leaked out around the parish that I was doing a graveside service for a gay man who died of AIDS, the response wasn’t all peaches and cream. The congregational president told me I shouldn’t do it. I told her she had no say on when or where or to whom I gave pastoral care.

I would have done it for anybody, with or without ever knowing Wayland. At least I like to think so. I cannot remember that graveside service without thinking of him.

Russell E. Saltzman publishes every Tuesday and Thursday usually by noon Central Time. He can be reached on Twitter as @RESaltzman, on Facebook as Russ Saltzman, and by email: [email protected].