A diabetic insulin reaction – low blood-sugar – induced a waking dream some nights ago. I was only was half-awake, perhaps half unconsciousness. I felt gauzy, detached; chimerical even. I was not uncomfortable. That was the problem. An insulin reaction usually is very uncomfortable until under control. I wondered why this one felt so different.

Blood-sugar reactions will typically send me and any other still-living diabetic into a panicked search for the nearest stash of carbohydrates. A carbohydrate infusion – candy bar, soda, anything fast – would raise my blood-sugar to less dangerous levels. Even in my stupor I knew my level was bad or getting there. I could feel it. I can feel both lows and highs. Too much of either will kill you, sure, but I just wanted to stay in bed.

I was relaxed and weirdly unconcerned. I was experiencing a sense that I could simply, no trouble at all, sleep on gently into death or, very much against my inclination, roust myself from bed, check my glucose levels, correct by eating a snack and spend the next hour wide awake trying to get back to sleep.

Problem was the snack was in the kitchen and to get it I had to leave my bed. My choice, but either way it would be alright. That’s what I was thinking the other night in my foggy insulin fugue.

Fellow diabetics will likely peg my sensation of gossamer comfort as just one of the array of symptoms of an insulin reaction: Confusion. But whatever else I was feeling I was not feeling confused. I was remembering old events with renewed clarity, and I did not want to leave the bed.

⊕ That time I was hospitalized for a bee sting, age 15 or 16. I shared a suite with one other patient, a noisy old man off the far corner repeatedly calling for a nurse, for his mother, asking where everybody was; talking to himself only half coherently. A bee sting at Scout camp and I almost died, hard wheezy breathing, painful red swelling at the site, a fever, and I could not go to sleep because this frightened man is making frightening clamors.

Then he got quiet. “Don’t worry, boy. It’ll be alright. You can go to sleep now.” He settled and we both got some sleep. I don’t remember him there in the morning.

Or did I have a little delirium? I was told mine was a “mild” allergic reaction; another would be more serious, dead serious. I should avoid bees, which – fools – is exactly what I tried to do with the one that hit me. Was the old man actually there? I’ve always thought so; never questioned it until my diabetic dream confusion. But while my insulin was bottoming out, it came to me – perhaps I was the one talking to an otherwise empty room? The voice was my own? I prefer to think not, but that’s another story. Yet in those slow moments when I still did not want out of bed it was what I was wondering.

⊕ I recalled a young mother, two kids, husband, a member of a parish I served as pastor in 1985 bordered hard against south Chicago. She was diabetic and had laid down for a nap, and never awakened. Never getting up is a symptom of blood-sugar gone too low. It was a shock to the congregation, and equally to me.

I could do that now, just drift away. I really did not wish to get out of bed. I wondered how she felt, the young woman I knew, while slipping from sleep to coma and on into death. Did she feel it at all? Why didn’t she awaken to an insulin reaction? I hope it was as soft and as easy as I was feeling.

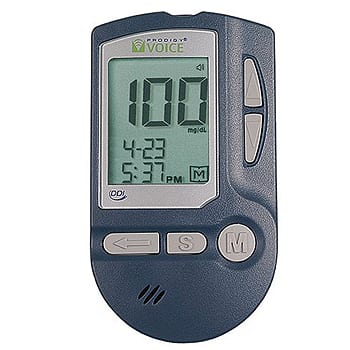

⊕ Diabetics having an insulin reaction are told to treat it by eating 15 carbohydrates and waiting 15 minutes. If there is no improvement, re-test the blood level and eat more carbs; always 15/15. A pin-prick to the finger and a squeeze of blood sme ared over a test strip inserted into a glucometer and one will know the blood number.There, treat that.

ared over a test strip inserted into a glucometer and one will know the blood number.There, treat that.

My problem is waiting 15 minutes for anything. I do not know any diabetic acquaintance who can patiently endure the gulping breaths, irritability, hunger, rapid heartbeat and some little cold sweat with a sweaty anxiety, dizziness, some confusion, and shaky hands while waiting for the blood-sugar level to creep up to a normal range over the long 15 minutes that stretch forever. Most of us cram down all the carbs we can find, right now, and then watch as the blood-sugar levels race above 200 or more and dose that with insulin to lower it. But, importantly, we feel better.

⊕ Most diabetics aim for a blood-glucose level nestled between 100 and 120, roughly an hour after eating. But quoting Pirates of the Caribbean, it’s more what you’d call a guideline than an actual rule. One-fifty, even one-sixty will do as nicely.

⊕ I once survived a level of 32. My diabetic daughter beat me at 30. We brag about those things to each other but we aren’t competitive too much, given the stakes. She has also been to the ER with a count of 600-plus; but she bounced back quickly and, in any case, knew more of diabetes than the ER doctor, which I point out is not an unusual experience for diabetics in the ER. But, still relatively unconscious, I’m in bed wondering if I can go for 29, just to tell her I’ve been there.

That’s the thought that finally got me up, staggering to glucometer and carbs. Maybe I could beat her number. I was at 42, low, very low, but not enough to best the family record. Well, there’s always next time.

Russell E. Saltzman, a former Lutheran pastor, lives in Kansas City, Missouri. His writing has appeared at Catholic World Report, First Things, The Hour of Our Death, among others. For many years he was editor of Forum Letter, an independent Lutheran publication, following the editorship of Richard John Neuhaus. His latest book may be found here. He can be reached by email, on Twitter as @RESaltzman, and on Facebook as Russ Saltzman.

If you have enjoyed this piece or other bits of writing (I have or may not have authored), please consider a small contribution. Click here (PayPal secure) and make a $1, $3, or $5 donation (if this pays off I may ask for more next time). Thank you.