WARNING: Spoilers abound (not that they really matter).

(Preface)

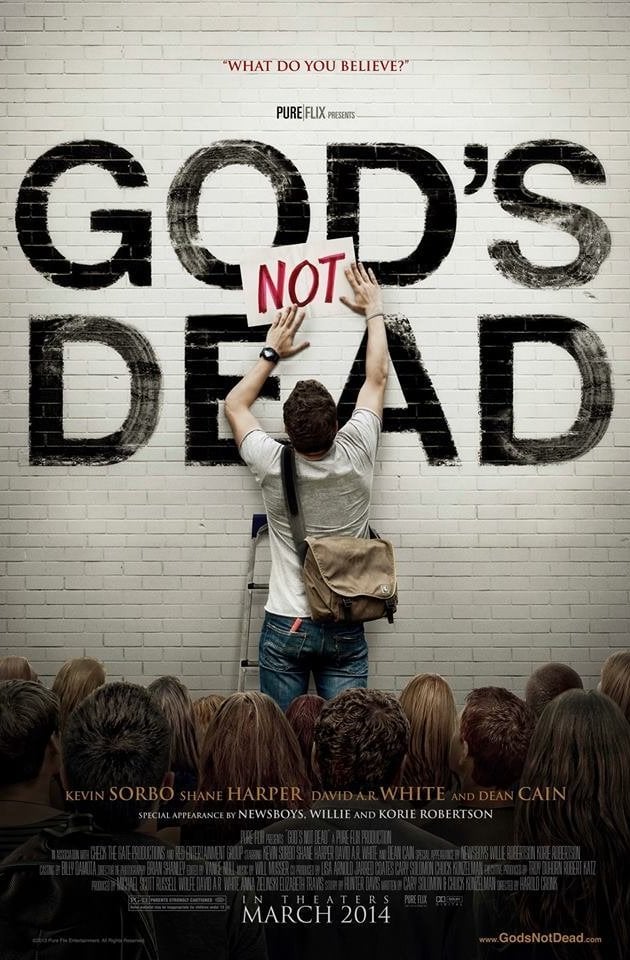

As a film, a work of art, a motion picture, a combination of acting, light, camerawork, editing, postproduction, color, music and more, as that sort of thing that is interested in beauty for beauty’s sake, a story and good writing and all the complexities of directing and the tragicomic, in that respect let me be very clear: God’s Not Dead does not qualify to be called a ‘movie’ in the artistic sense. To judge it alongside the Coens, Anderson, Tarantino, and Malick is to make a serious category mistake.

Of course the acting is horrid. Yes, as you may expect, the writing is awful. Do I really need to mention that the scenes are predictable? Obviously the plot was nonexistent and the cameos of Duck Dynasty and the Newsboys were, oddly enough, a laughable relief. But there is still something important and powerful to see here. I will not dismiss God’s Not Dead on its absolute, total, and irredeemable failure to even aspire to become art. After all, cinema isn’t exactly artsy these days and my unrefined palate believes that Anchorman 2 was the best movie I saw last year.

But maybe I’ve been too harsh. After all, there is a view (that I tend not to hold) that art is simply a matter of producing real phenomenological affects. Art is what connects and makes the person under its influence think, feel, and be. If that’s the case, then, perhaps, God’s Not Dead is, by a long shot, the best movie I’ve seen this year. Napoleon Dynamite was more satisfying and cathartic, to be sure, but it didn’t leave the impression this film did. It was enjoyable and niche, this was painful and accessible.

You could almost say that God’s Not Dead is more documentary than fiction. I was left with the uncanny impression that there is something very real here, for better and for worse.

Needless to say, this review is going to be long and hard because I think this thing I saw last night — whatever we decide to call it — is interesting in many different, conflicting, and rich ways, especially for Catholics and people of faith in general.

*

Many people overlook the most important evangelical tool in the arsenal of youth ministry retreats, conferences, and alike: shitty plays. They are all the same play, really, and the acting can sometimes improve them, but most of them are fool proof. They often rely on music, like the overused “Turn Around” schtick of the late 1990’s. The point is that a play, even a bad one, often functions as more of an argument than an argument. It delivers a convicting message, packaged for an everyman that can cover middle school to mid twenties.

What is perhaps most astonishing is how these canned, formulaic, and homemade skits can so routinely have such powerful and vivid emotional effects and manifestations. Especially when followed by music, therapeutic prayer, and psychoanalytic preaching.

In this respect, those who dismiss God’s Not Dead as being built on a mountain of bad arguments, faulty assumptions, and the rest miss the point: the performance belies the content.

There is little doubt that this movie succeeds tremendously in utilizing every evangelical trope of what I would call “cool Christianity” from the last twenty years. From the conference echo, “God is good? ALL THE TIME! All the time? GOD IS GOOD!,” to the more understated (but hardly subtle, as there is nothing subtle in this film) behavior and mannerisms that display the sort of balancing act that this type of evangelical style uses to keep its edge.

For example, the film opens with romance: the feature protagonist — a tall, white, athletically built, baby-faced attractive college freshman, wearing a plaid shirt unbuttoned with a Newsboys t-shirt underneath (I told you there was nothing subtle!) — and his stylishly white, blonde, thin, and borderline sexy (but never too sexy!) girlfriend who ends up leaving him (the “pressure from the girlfriend” problem is a common one that always gets touched on by ministry of this sort). The image of them walking affectionately on the lawn together, is instantly attractive in all the ways that marketing experts understand. The message is univocal: Christian are attractive, mainstream, and can even have hot boy/girl friends. I don’t think the word ‘sex’ appears in the film, but there are two telling signs of physical affection that show more than can be said: a kiss from each young lover, one on the side of the head from the boy, the other on the cheek from the girl.

Here, again, the juxtaposition is identical to what I’ve seen in so many youth groups. You can have it all and still behave. Of course, us Catholics sometimes push this even further with the erotic morning sessions on theology of the body and porn and other things that usually create a unique sexual tension. The hugging and affirming culture of cool Christianity can, I think, be read almost entirely from this sort of fiercely repressed tantric piety.

That is but one small example of a text filled with instantly recognizable, and perfectly executed, themes and issues. As a result, you could say that God’s Not Dead is a perfect youth retreat, packaged inside 113 minutes. It has the identical effect that “Jesus Freak” had in its day, but it is now much more refined, intentional, and polished.

*

I don’t have space or time to do more than assert that there is a rigorous sense to the meta-apologetics of the film. I can already imagine a companion text, that replies to objections, citing each scene that proves that the film does not, for instance, say that all philosophy classes are taught by atheists (there is a very clearly marked scene where the film sort of telegraphs that “THERE ARE OTHER PHILOSOPHY CLASSES! WE ARE NOT GUILTY OF MAKING THAT ASSUMPTION HERE!”)

The addition of complexity, however, is more strategic than paradoxical, and for good reason: this is apologetics after the fact. This film is, really, something of a eulogy for a world that never was, but surely will never be again for quite sometime. This is about America. The patriotic theme is never done in a wholly objectionable way, but it’s there. The American flag, for instance, pops in and out, and always belongs on the side of God. Despite the bandana worn by Willie Robertson (from Duck Dynasty), the more interesting placement was a quick, glancing shot of the US flag inside the also fascinatingly generic, but rather “high church” looking, sanctuary.

*

When the sentiment of a scene ran completely raw, even the apologetic balance was lost and this was the main flaw in the evangelical delivery as far as I could tell. This blindness also revealed how an aesthetic disaster can lead to perversely unreflective violence.

Two examples, to prove my point: the most violent scenes are (a) when a Muslim woman — there is an early and consistent subplot of a Muslim women who converts to Christianity (using an oddly liberationist counterbalance between her traditionalist father and the glitz of the Newsboys’ American Christianity) that is very disturbing and, in my view, the oddest and most regrettable part of the movie — is physically abused by her father for refusing to reject Jesus, all this playing out in front of her son, the father’s informant, and (b) when the chief antagonist is struck, almost laughably (recalling the absurdly telegraphed car crash in Remember the Titans), by a car, which leads to his death in the rain, just after accepting Jesus and getting saved with prompting from a pastor and his African friend who is also a pastor.

a. The brutality of the woman-beating scene was jarring and it was clear to me that the people who made the film didn’t have clue what they were doing. This was a very MANLY movie. After beating his daughter and throwing her out of his house, the father collapses in tears in what is supposed to add complexity and humanity to a scene where a petite woman is back-handed by her large and “angry-Arab”-looking father, as her son weeps. If anything, her bravery was the only real sacrifice of the entire film, yet she was cast as a minor role, supporting the narrative of the guy who only loses his hot girlfriend and never shows more remorse or pain than a pensive shaking of the head.

b. The evil philosophy professor, who rather inexplicably forces his class to write “God is dead.” on a sheet of paper and aggressively treats his students like idiots, is chasing after his lost love, a former student, who is attending the same Newsboys concert everyone else in the movie managed to be at. As he crosses the road, he gets hit by a car, right in front of the pastor and his African friend who are trying (in another very odd subplot) to go to an amusement park. All of this in the pouring rain, mind you. The African pastor diagnoses the professor, on sight alone, as having crushed ribs, awaiting a certain death within moments. In that short time, the other pastor tells the dying man that God saved him from dying on impact so that he could accept Jesus and get saved. (What struck me about this scene, and another one where the Newsboys pray for another subplot women who is dying of cancer [long story here, but equally as oddly paced and laid out], is how the posture of the people in the scene was identical to that of people praying over each other, preaching, and alike in hip Christian circles. The way they fold their hands, which isn’t too religious-looking, but shows piety.)

Despite these two rather awful — one despicable and repugnant, the other laughable and outrageous — climatic scenes, the movie otherwise manages to not go obscenely overboard, even when it accelerates in other ways.

*

The effect is perfect, really. What kind of person do you want to relate to? The persecuted saint (who is actually not persecuted that much, so don’t worry about taking this thing too far and being uncool or weird) or the giant asshole (who is totally corrupt and empty inside until Jesus relieves it altogether).

And what will you do about it?

Send a text message. Seriously, send a text message.

Really, this was brilliant: the film had three “altar call” moments, two in the film itself and one with the option to participate. The first was when the philosophy classroom, sparked by another subplot of a Chinese student who rejects his father’s secular state atheism, stands up and declares, one by one, “God is not dead.” The second is when all these subplot members make their way to the Newsboys concert. This part is effective because it has the “gathering song” effect that is so typical of youth conferences and retreats. The third is when Robertson returns, via big screen at the Newsboys concert, and tells the Jesus-filled crowd of ten thousand (and everyone sitting in the movie theatre) to text “God’s Not Dead” to their entire contacts list.

I guess this is the New Evangelization, right?

Who knows. But I suspect that this is precisely what we’ve been fawning over Matthew Kelly for: better marketing, positive branding, fuel for the big bad world out there, set to destroy and eat us like the lions of the Colosseum.

*

I was shocked at my reaction. I choked up more than once. Some of this is simply the fact that my emotions are hair-triggered to begin with. But some of it was, frankly, shocking. I knew the game and the rules and the rules behind the rules, and still, the message had a particular resonance with my at a very basic affective level. Let no one doubt the bare reality of the evangelical Christian metanarrative: it works. Without the two blunders I mentioned, this movie may have even been persuasive in a way that would have been alarming and alluring.

I was also filled with a sense of fear and sadness when thinking of the present state of Christianity in the United States. I thought of my own work, this blog, my music, the album I’ll be recording in two weeks, the academic work. There needs to be more than just an alternative, I think; we must do more than give a better option. The problem is more fundamental.

I do not want to politicize these facts, but they are absolutely present and real: this is a film about and for suburban, college-going, mostly white (but increasingly cosmopolitan), privileged Americans (who say nothing at all about sexuality, despite facing very real questions of love, loss, and death) who live in a world where you have to be a certain kind of Christian to survive. This is the generation of young people who don’t bother to read the Book of Job.

*

I felt deeply moved and confused and even a bit dumbfounded at my response to God’s Not Dead. I hated it and I think I liked it. I think it borders on the idiotic and, somehow, manages to be an almost flawless and self-consistent form of apologetics. Most of all, I saw myself in it, past and present, and I saw where we are, as Catholics, stuck between this sort of caricatured garbage and the rancid and cynical “none.” Surely there is more than better options. But that doesn’t cleanse the sense I have that God’s Not Dead captured a better picture of the present state of Christianity (and philosophy!) than I’d like to believe is true.

*

Unlike the evangelical style of, for instance, “Campus Crusade for Christ” or other bygones of that era, there is something unique about this film that, in closing, I’d like to mention:

1. Jesus has a very minor role in the film. In this respect, this is not the “Jesus Freak” generation; this is the God’s Not Dead generation. I think it is fairly clear which claim is countercultural and which one is defensive and paranoid.

2. Science is engaged with in a way that was not of the Young Earth creationist variety, and even seemed plausibly evolutionist. That was refreshing, mostly, but also rather unconvincing, since the arguments boiled back down to a literal reading of Genesis. Nonetheless, as noted in point 1, rather than proclaim “Christ crucified,” or something radical like that, the movie seemed to assume that asserting the metaphysical existence of God is identical to belief in the God of Abraham, and Jesus Christ, which is problematic (especially when considering the Muslim aspect).

3. I could write a whole book on the ways that teaching and pedagogy were portrayed in the film, but I won’t do that now.

4. It is decidedly protestant. I know that calling protestants protestants ruffles a few people’s feathers nowadays, but it’s true. That I find it relatable is another difficult explanation that I won’t bore you with, but let’s just say that I’m not exactly feeling ecumenical about this movie.

5. The credits display and pay tribute to a number of cases where religious groups were censored by public universities. This gives it a “religious freedom” or “student/youth movement” feel. Despite this link, the movie still felt desperate. It seems to proclaim it’s antithesis: God is dead, hence the need for the mass text message trolling. Of course, we’ve known about God’s demise since Nietzsche stole it from Hegel, but here the horse is dead enough to become alive again.

*

(Epilogue)

We live in the age of the undead God, the God who is merely not dead, but can hardly be called alive. This is a zombie Christianity. These are apologetics that risk nothing and grant even less in advance; this is love with conditions and straw men who burn with a zeal that shows them to be faking it, too. New Atheism, Bill Maher’s smart-assery, Contemporary Christian music, that privileged sort of suburban tie-dyed t-shirt wearing youth ministry*, and God’s Not Dead all belong together. They are obsessed with each other. And they all have things to sell.

What was most real to me about God’s Not Dead was how fake it was, and how artificial a film it takes to portray the unwitting image of followers of Christ in America today. This may be an unfair image, but, making films (and retreats and conferences and music) like this, we damn well deserve it.

*You may also want to read an earlier post, An Aesthetic Critique of Youth Ministry: Miley Cyrus vs. Bonnie Raitt.