I was 27 years old when I was diagnosed with breast cancer.

I’m 37 now.

In some ways, it seems impossible that a decade has passed. It seems like it was yesterday that I was sitting on an exam table in a gown in a chilly exam room in my surgeon’s office hearing the words “You have cancer,” words that sounded more like a death sentence than a diagnosis.

And in other ways, it seems that in the past decade, I have lived more than a lifetime. A lifetime of surgeries, infusions, infections, blood draws, shots, scans, body aches, fatigue, scars, hot flashes, insomnia and grief.

But the further I travel from that diagnosis in my past, the more it feels like I’m looking at it growing smaller in the distance, as if the cancer diagnosis is shrinking in life’s rearview mirror.

The question I have been asking more and more is not what to do with my past, but what to do with my future.

What do I do with, as Mary Oliver so well put it, this one wild and precious life I’ve been given?

This semester I’ve been on lots of university campuses, and I’ve done an activity with students that helps them clarify what their unique vocation might be. (The questions are here if you’re interested.)

The last thing I ask them to do is to write their personal mission statement in a sentence. Which mean that I had to write mine, too.

Here’s what I said:

“I want to use writing and medicine to bring emotional, spiritual and physical healing to our beautiful, broken world.”

I hope that with my writing and speaking I accomplish part of this — I help people experience stories, heal from their own experiences, and learn to see the world through the eyes of God. To be people of Red Doors, to be people of Love, to be people who learn to Look Around and see those who are marginalized and invisible.

And increasingly, I’ve been able to use my degree in medicine to accomplish my mission statement of bringing not only emotional and spiritual, but also physical healing to the world. I have worked in ER/Urgent Care medicine in the U.S. for the past 12 years.

And then, in January of 2015, I had the opportunity to travel to Ecuador with Compassion International to visit a site there. After spending a day at the center watching children learn, play and be loved on by their mentors, our group split up, and we went to the children’s homes to see what the living conditions were like.

The home I went to was a one-room mud hut with a thatched roof. A woman whose weathered face made her look decades older than she was came out of the home to greet us. I could see she had been crying. As we arrived, she used the back of her hand to wipe the tears away, and I noticed the callouses, and the dirt under her nails, telltale signs of how hard this woman worked.

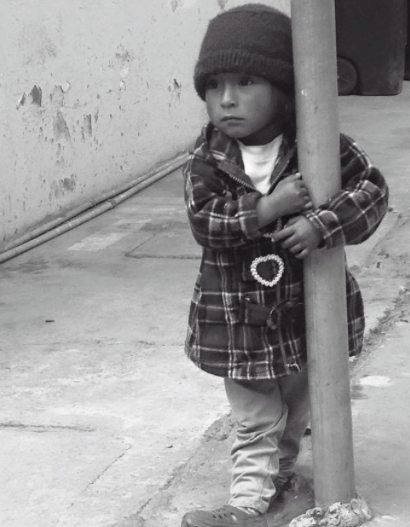

A toddler and a pre-schooler clung to her skirts. Her 7-year-old son, who I’d met at the center earlier that day, came around the corner from where he’d been hoeing the family’s potato field.

Our guide, an Ecuadorian woman who worked at the church, did weekly visits to each Compassion child’s home, so she knew the families and their stories well.

“This woman is very sad,” our guide explained to us. “Her baby died last week.”

“How did the baby die?” I asked softly.

The guide went on to explain that the baby, who was only a few weeks old, spiked a fever. The mom had been given a bottle of liquid Tylenol by volunteers who came to the village a few months before. But the mom had no idea that Tylenol needed to be dosed by weight. So she fed the baby the entire bottle, and the baby died of liver failure.

Our group did other things that day. We visited a few other homes. We fed chickens. We pulled weeds. We picked up hoes and rakes and worked in the families’ fields. But honestly, the rest of the day was a blur because I kept seeing the weeping, weary woman’s face, and I kept thinking of the unnecessary death her baby had died — joining the 6 million children under the age of 5 who die in the developing world every year, mostly from preventable causes.

The grief I felt that day turned into anger, which turned into motivation to do whatever I can to keep those deaths from happening.

I signed on as a spokesperson for Compassion International, and wherever I speak, I ask people to become sponsors, to invest $38 a month to save these precious little lives.

And I have started practicing medicine internationally, putting myself in harm’s way and taking personal financial and physical risks to get to these kids and do what I can to save their lives.

I went to Togo for 3 months last year and worked at a hospital there (and nearly died of malaria). Then in April, I went to Kenya for a month and started a clinic at a school for orphans in rural western Kenya (and contracted Typhoid and malaria.)

Next month, I have the opportunity to travel to the Dominican Republic to work at a medical clinic there, make house calls to people in remote villages that can’t get to the clinic, and do training with pregnant and new moms on how to take care of their babies — an opportunity that is especially close to my heart given the grieving mom I met in Ecuador.

Caring for people in the developing world — and writing their stories — is the best way I know to honor the life I’ve been given, and to celebrate the ten years its been since my cancer diagnosis.

I’m raising money on GoFundMe to cover the expenses of my trip, and to be able to gift the clinic with all the supplies and training materials they need to be able to provide education and care for the people they serve.

If those who can will give just $10, it won’t take long to raise enough money to bless the clinic and the people of the Dominican Republic with plenty of medicine, equipment, supplies and educational materials to be able to not only survive, but begin to thrive in this one fragile, priceless, wild and precious life.

***

Click here to donate to GoFundMe.

Click here to sponsor a child with Compassion International.