Connor Wood

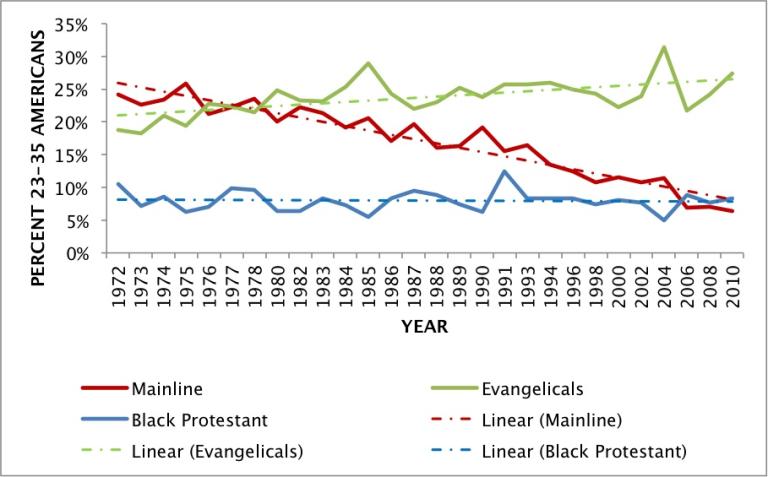

Liberal Protestantism is dying. Rod Dreher says so in a recent column in The American Conservative, and the statistics back him up: for decades, liberal and mainline Protestantism has been on the decline in the US, with some denominations (such as the United Church of Christ) losing adherents so quickly that their future is in peril. Meanwhile, more conservative and evangelical denominations have generally held their own, or even experienced growth (see graph below). But liberal Protestantism in many ways exemplifies the best of what religion could be: it’s tolerant of differences, non-judgmental, open to scientific knowledge. Good stuff, right? So why is it that the open-minded liberal churches are dying out?

In his American Conservative post, Dreher – who’s recently published a memoir about rediscovering his roots in his small-town, religious Louisiana – suggests that the decline is partly because conservative Protestants are better at forming community and articulating a clear mission than liberals. This is almost certainly true, but it raises a further question: how exactly do conservative churches do a better job of forming community? Do they hypnotize their members? Brainwash them? Spike the Kool-Aid with mind-control drugs?

Well, the first thing we have to realize is that conservative churches are almost always stricter than their liberal counterparts. They demand more investment, require their members to believe in more rigorous, exclusionary creeds, and don’t look kindly on skipping church four Sundays in a row to sleep in.

In the early 1990s, a political economist named Laurence Iannaccone claimed that seemingly arbitrary demands and restrictions, like going without electricity (the Amish) or abstaining from caffeine (Mormons), can actually make a group stronger. He was trying to explain religious affiliation from a rational-choice perspective: in a marketplace of religious options, why would some people choose religions that make serious demands on their members, when more easygoing, low-investment churches were – literally – right around the corner? Weren’t the warmer and fuzzier churches destined to win out in fair, free-market competition?

According to Iannaccone, no. He claimed that churches that demanded real sacrifice of their members were automatically stronger, since they had built-in tools to eliminate people with weaker commitments. Think about it: if your church says that you have to tithe 10% of your income, arrive on time each Sunday without fail, and agree to believe seemingly crazy things, you’re only going to stick around if you’re really sure you want to. Those who aren’t totally committed will sneak out the back door before the collection plate even gets passed around.

And when a community only retains the most committed followers, it has a much stronger core than a community with laxer membership requirements. Members receive more valuable benefits, in the form of social support and community, than members of other communities, because the social fabric is composed of people who have demonstrated that they’re totally committed to being there. This muscular social fabric, in turn, attracts more members, who are drawn to the benefits of a strong community – leading to growth for groups with strict membership requirements.

The evolutionary anthropologist William Irons calls demanding rituals and onerous requirements “hard-to-fake symbols of commitment.” If you’re not really committed to the group, you won’t be very enthusiastic about fasting, abstaining from coffee, tithing ten percent, or following through on any of the other many costly requirements that conservative religious communities demand. The result? Only the most committed believers stick around, benefiting from one another’s in-group-oriented generosity, social support, and community.

Other researchers have empirically tested Irons’s theory. In 2003, anthropologist Richard Sosis and psychologist Eric Bressler conducted a retrospective study of American communes in the 19th century. They searched for data about how strict those communes were – whether they demanded that members abstain from coffee, give up all their money to the commune, or even surrender their parental rights over their children (!). As the researchers expected, religious communes whose membership requirements were strict and demanding survived, on average, many years longer than those without strict demands.

Since then, Sosis has also demonstrated that religious Israeli kibbutz members are more generous in resource-sharing games than both secular, urban Israelis and secular kibbutzim. He argues that this is, in part, because demanding rituals – such as having to pray three times a day and study Torah many hours a week – serve as a signal of investment in the kibbutz community. The more rituals you participate in, the more invested you feel – and the more willing you are to sacrifice for your fellows.

But if your community doesn’t have any of these costly requirements, then you don’t feel that you have to be really committed in order to belong. The whole group ends up with a weakened, and less committed, membership. Liberal Protestant churches, which have famously lax requirements about praxis, belief, and personal investment, therefore often end up having a lot of half-committed believers in their pews. The parishioners sitting next to them can sense that the social fabric of their church isn’t particularly robust, which deters them from investing further in the collective. It’s a feedback loop. The whole community becomes weaker…and weaker…and weaker.

Which is too bad, because the theology of liberal Protestantism is pretty admirable. Openness to the validity of other traditions, respect for doubters and for skeptical thinkers, acceptance of the findings of science, pro-environmentalism – if I had to pick a church off a sheet of paper, I’d choose a liberal denomination like the United Church of Christ or the Episcopalians any day. But their openness and refusal to be exclusive – to demand standards for belonging – is also their downfall. By agreeing not to erect any high threshold for belonging, the liberal Protestant churches make their boundaries so porous that everything of substance leaks out, mingling with the secular culture around them.

So what if liberal Protestants kept their open-minded, tolerant theology, but started being strict about it – kicking people out for not showing up, or for not volunteering enough? Liberals have historically been wary of authority and its abuses, and so are hesitant about being strict. But strictness matters, if for no other reason because conservatives are so good at it: most of the strict, costly requirements for belonging to Christian churches in American today have to do with believing theologies that contradict science, or see non-Christians as damned. What if liberal Protestantism flexed its muscle, stood up straight, and demanded its own standards of commitment – to service of God and other people, to the dignity of women, and to radical environmental protection? Parishioners would have to make real sacrifices in these areas, or they’d risk exclusion. They couldn’t just talk the talk. By being strict about the important things, could liberal Protestant churches make their followers walk the walk of their faith – and save their denominations in the process?

Check out my research team’s survey website, ExploringMyReligion.org, for more about liberalism and conservatism in religion.