Last time, in throwing in my two cents on the discussion of “civility” in debate prompted by Elizabeth Stoker Bruenig, I distinguished between two different meanings of that word: civility as adherence to a speech code, and civility as an effort to understand your opponent, to speak their language. I said the first was very much optional, and the second strongly recommended. But there’s a third definition of civility which, in my view, should be defended in absolute terms. It’s civility as charity, civility as recognition of innate human dignity. That’s a bit imprecise, so I’ll unpack exactly what I mean: I mean that we should never in discourse try to judge the state of anyone’s heart, and I mean that we should never dehumanise them, regardless of how horrible their actions are. In Elizabeth Stoker Bruenig’s second post on civility, this was the passage that challenged me most, that made me stop in my tracks and reassess what I believed about the issue.

***

not all ideas should be treated as though they’re equals. It’s tempting to imagine a Magister Ludi-like scenario where smart people go around all day in fraternal disagreement, catching each other dreamily by the sleeves when they pass in the airy stone colonnade, saying: “Hey, friend, didn’t you mention you’d like to make poor children feel terribly ashamed of themselves for eating free school lunches? You know I’ve often thought that was a favorable notion, but I have found myself lately wondering…” But not all ideas are really so noble, not all ideas even have an ounce of goodness in them, and we do ourselves no good by pretending people who want to shame poor kids are ultimately fine Joes who have just got some odd ideas, and should therefore be treated with the utmost sweetness. You might be a fine Joe in other respects, but when it comes to your ideas about children, you’re a terrible Joe. You will be treated, on this account, as a terrible Joe. I’m not saying I’d not be kind to you outside this discussion, but as a matter of deliberative discourse, your fine Joeness has been found wanting and will be noted as such. I used to belong to a crowd that was all about being a very open intellectual community. I liked it, but it began to occur to me that our discussions were a lot more like AA meetings than debates: we were so invested in affirming the inherent value in having an idea that we wound up over-affirming people who had terrible ideas, and they persisted in the keeping of these ideas because while they had been shown they were wrong, they had never been made to feel they were bad. I realized then that there’s actually a little danger in the affirm-first, question-later approach.

Elizabeth is right. There is a danger of over-intellectualising debates that have real stakes, of making a game of the discussion of ideas that, if implemented, could reshape real people’s lives for great good or great ill. But ultimately I can’t go as far as she does. Because I don’t think I’m qualified, and I don’t think anyone else is either. There are three questions that Elizabeth is dealing with here. The first is: can ideas be bad? Of course they can. “Shaming poor children for receiving government aid is OK in the service of a greater good” is a terrible, abhorrent idea. So are “torturing people is sometimes legitimate” and “infanticide is morally acceptable because children aren’t self-aware”. The second is: can a person hold a terrible idea because of a lack of virtue? Again, the answer should be an obvious yes. To take a totally trivial example, I’ve switched my allegiance between “everyone should do an even share of the housework” and “people should just chip in gratuitously without bean-counting” depending on which would minimize my dish-washing load on a particular day. People do all sorts of things out of a lack of compassion, or humilty, or chastity. Of course they’ll sometimes end up embracing ideas for similarly base motives. The third question is: can we know that a given person is holding a terrible idea because of a lack of virtue on their part? No. No we can’t. We simply don’t have the information. We cannot know the state of another’s heart. We cannot know whether they are acting out of malice, self-interest or or cowardice – or if they’re honestly mistaken, invincibly ignorant, or operating out of an internally consistent ethical framework that they haven’t been shown the fatal flaw in yet. I, like Elizabeth, am pro-life. I think all direct abortions are wrong. But I have a particular horror at late-term abortions because, not only are they wrong, but they seem to me obviously so. One needs no grounding in Christian ethics, no philosophical training to see that a fetus in the second trimester onwards is clearly a baby. To borrow from Lincoln’s words on slavery, I think that if late-term abortions are not wrong, nothing is. And yet, I know and love people who disagree with me on this, who think that some late-term abortions are morally licit. Some disagree with me about dependence and bodily rights. For others, some of the hard cases are just too hard. I am just not convinced that these people disagree with me because they lack virtue. Could they have done more to study the issue, to read the best arguments, to confront the reality of what they support? Certainly – I live in hope that they someday will. Are there good reasons why they have not yet done this, circumstances that would make it very hard for them to join me on what I believe is the side of right? I don’t know. I simply don’t know. And not knowing, I follow the pretty clear instructions I’ve been given on the matter.

Judge not, lest ye be judged.

St Paul says something similar in his first letter to the Corinthians:

Wherefore judge nothing before the time, until the Lord come, who will both bring to light the hidden things of darkness, and make manifest the counsels of the hearts; and then shall each man have his praise from God.

Now, Jesus did call the Pharisees “whited sepulchres”. But he was, (like Roger Ebert in a very different context), qualified. He was without sin. He was entirely within his rights to cast that verbal stone. He was God. I am not qualified. This isn’t to say that we should ignore vested interests (when the Irish drinks industry starts campaigning against a ban on alcohol advertising in sport, it’s legitimate to raise an eyebrow). But, I repeat, we cannot know about personal motive, we cannot read minds or look into hearts. So I have to again part ways with Elizabeth when she sketches out the following scenario:

You’re a Christian who’s really interested in developing a ‘culture of life.’ You notice someone arguing we should shame poor kids in order to reduce welfare participation. Arguing that it wouldn’t reduce welfare participation is one route, and you do this — but there’s something else you want to argue against, too: the idea that being a person who shames poor kids is acceptable. So you let the interlocutor proposing this idea know he’s a bully picking on people who aren’t present to defend themselves, and that the proliferation of characters like him in politics is a cancer on society and antithetical to building an authentic culture of life.

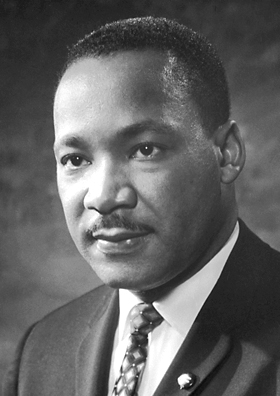

But we do not know whether he’s a bully or not! That’s the thing! But – but – even if we knew for certain that he was, it still wouldn’t be remotely OK to call him a cancer. I just wonder how Elizabeth would react to being told that the proliferation of “characters like her” in public life was a cancer? Let’s say an imaginary right-winger was calling out “dependency-creating statists” who kept the poor trapped in poverty with their soft bigotry of low expectations? (To be clear here, I agree with Elizabeth on the vast majority of economic and distributional questions). What if this person considered that the proliferation of characters like her in politics was a cancer? I don’t think she’d like it at all. And she’d be right not to – because people are not cancers. Not ever. Actions can be cancers. Particular arguments can be cancerous. People can, over time, warp themselves and orient themselves towards evil. But they do not ever become cancers. They are still, in themselves, children of God, people with inalienable dignity. Nobody, be they the poorest of the poor or a greedy hedge-fund manager, is a cancer, and calling them such is wrong. And not only wrong, but unnecessary. No stinging critique, no prophetic denunciation loses its power because it decries actions rather than people. “You are doing a terrible thing” is no less forceful than “you are a terrible person” – but it’s a lot more honest. Martin Luther King did not have to give up anything worth keeping when he condemned segregation while hoping and praying that its supporters would change rather than vanish (cancers do not reform – they destory or are destroyed). And if he could win his great victory without condemning anyone, then why should we settle for less? In conclusion: I think Elizabeth Stoker Bruenig is a brilliant writer and a razor-sharp, truly orginal thinker. In all her interactions with me she has always been extremely gracious – discussing and debating with her is always a pleasure. She has made points on civility that are both correct and important. But on civility as charity, on civility as refusing to judge, she is cataclysmically wrong.