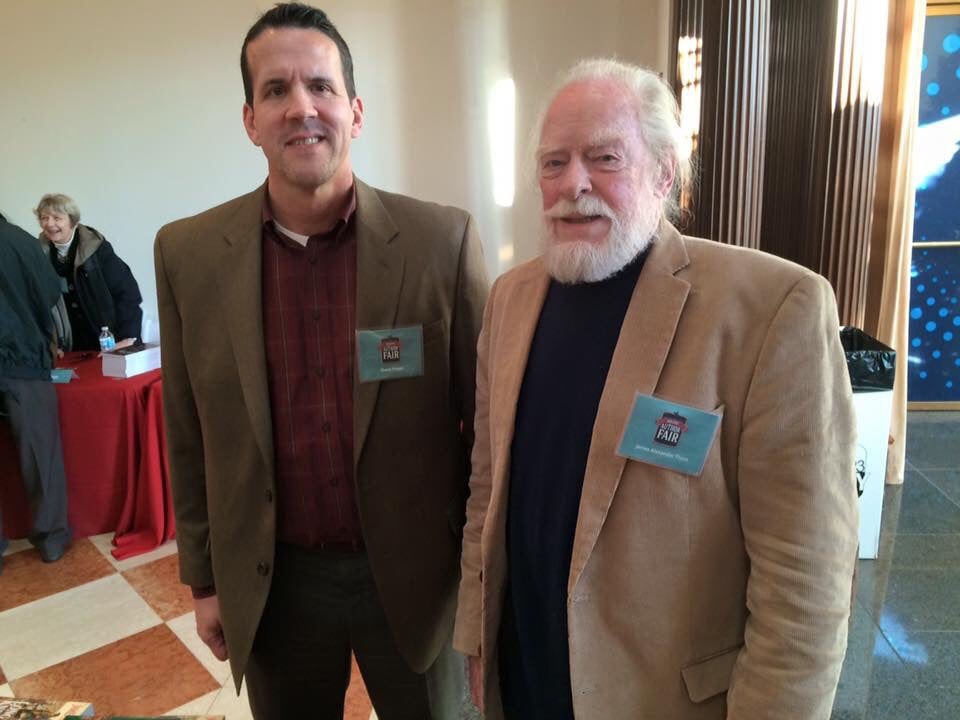

My recent foray into the strange new world of being an author has put me into the position of getting to meet and spend some time with some people that I have admired for a long time. At the top of that list is a man who I consider to be my idol as a reader of, and now writer of historical fiction. James Alexander Thom is on a short list of the very best in that genre. He will be remembered in the same stratum of the greatest writers Indiana has ever produced, and that is a very impressive list! His books have sold millions of copies and some are required reading in high schools and universities around the country.

My recent foray into the strange new world of being an author has put me into the position of getting to meet and spend some time with some people that I have admired for a long time. At the top of that list is a man who I consider to be my idol as a reader of, and now writer of historical fiction. James Alexander Thom is on a short list of the very best in that genre. He will be remembered in the same stratum of the greatest writers Indiana has ever produced, and that is a very impressive list! His books have sold millions of copies and some are required reading in high schools and universities around the country.

Before the recent Indiana Historical Society’s Holiday Author Fair, I reached out to James in an email to let him know that I was going to be one of the authors there with him this year. I told him what a great influence he had been on my career as a teacher and, now, writer, and how much I looked forward to meeting him. He wrote back a nice letter and we have been corresponding regularly since.

He graciously agreed to allow me to interview him for my blog. What follows is that interview, in its entirety. I am very humbled by this whole experience. I am also very happy with this interview. I think teachers, writers, and history lovers alike will benefit from reading it. Enjoy and share.

Me: First of all I want to thank you again for agreeing to do this interview. We have spoken before about the fact that your work has had a major impact on me as a historian, teacher, and writer. I consider it a great honor to get to “pick your brain” a little bit. I know you are busy working on your next project, so I appreciate you taking some time to answer a few questions. I am sure there are many others like me who could benefit from your sharing your experiences with us.

How many historical fictions have you published now?

Thom: I’ve written ten historical novels, including Warrior Woman, co-authored with my wife.

Me: I know it is probably like trying to name a favorite child, but if you were forced to choose, which of your novels would you say is your favorite, and why?

Thom: The favorite would be Panther in the Sky, because it expanded my conscious and took me into another culture, and brought my wife and her people into my life.

Me: I wanted to get a little bit of info about the mechanics of writing that would be interesting to other writers who may read this. If you will, walk me through the typical process you go through when you write a book. I know that you are famous for your meticulous, hands on research. When, then, does the writing process begin and what form does it take? Outlines? Long hand, typewriter, or computer? How far do you go before you edit/re-write? Do you have anyone give you feedback as you go? Where and when do you prefer to write? How often?

Thom: The mechanics have changed over the years, as publishers now insist on discs rather than paper manuscripts. As much as possible, though, I do it the old way: handwriting, then pencil-editing on that until I feel ready to make the first typescript on the typewriter. There may be several typescripts before I’m ready for anyone to see it. Any change made in a novel reverberates throughout, so I must be able to spread paper manuscript chapters out on a table and revise every sentence that’s affected. If it turns out that the first version was better, I need to have it where I can retrieve it. Who sees the manuscript, and when, also varies. For 25 years I had the ideal editor at Random House, with almost infallible literary intuitions and clout in editorial meetings, plus a top agent. Now I have no agent to go through, and a different editor, so I rely more on my own editorial judgment. I have certain astute friends who are established writers, and I might ask them for an opinion that I would have referred to my old editor. When I finally enter the manuscript into the computer, any changes I make then I note on the paper version. I revise as long as I can, and how long I can do it depends on what deadlines I’ve agreed to. The Eli Lilly Library at Indiana University has been collecting my notebooks, literary papers and manuscripts for years, so all that mass of stuff is now in better order than I could have maintained.

Me: No doubt the book that brings people to know your work more than any other is Follow the River. I have read that this book, first published almost 35 years ago, still sells in the neighborhood of 30,000 copies a year, which is astounding to me. To my mind, Follow the River is perhaps the most intense depiction of human endurance I have ever read. I have read that you did some pretty strenuous work yourself to research for this story. Can you talk a little bit about what you put yourself through in preparation to tell that story, and why you felt that it was necessary to do so?

Thom: Follow the River has sold nearly 1 1/2 million paperback copies, is in its 49th or 50th printing, still outsells any of the others, and is considered a “classic,” but no longer sells 30,000 copies a year. If that figure is on the website, I need to change it. Much of my research for that book was grueling, because I needed to be able to describe not just physical hunger and exhaustion,but also the effects of fatigue and hypothermia on the human mind and spirit. I knew from certain extreme experiences in my younger days that judgments made in those conditions can be very bad, even fatally so. We modern Americans are so far removed from basic hardship that the story can’t be told truly without making the reader “suffer” with that doughty survivor.

Me: I was happy to hear you say your personal favorite of your own works is Panther in the Sky. I would have to say that it is mine as well, and the one that has influenced my own work the most as both a writer and a history teacher. My personal feelings about Tecumseh are that he is as great a leader as America ever produced. I believe he deserves a place alongside the men on Rushmore. I would love to see him replace Andrew Jackson on the $20 bill (wouldn’t that send Old Hickory spinning in his grave!) You seem to have a very intimate connection to Tecumseh and I don’t think anyone has told his story better or with more compassion and respect. I know your wife, Dark Rain, is Shawnee like Tecumseh. Talk a little bit, if you would, about what Tecumseh and the Shawnee people, in general, mean to you personally.

Thom: I agree that Tecumseh was our most exemplary patriot. He gave his whole self to the protection of his people and their sacred land. Until then, I had been telling of the frontier struggle through the pioneers’ eyes. I wondered how the Shawnees had so effectively resisted the invasions of the more numerous and better-armed whites for so long, and so I determined to find the sources of their strength and courage. Tecumseh and his culture were so unknown to me that I doubted that I could do justice to the story. It was only after the Shawnees came to trust my motives and let me into their sentiments and ceremonies for three years that I was ready to try. By then I felt more like an Indian than a paleface. When their chief read the manuscript, he said it was a book that only a Shawnee could have written, and I was invited to be named into the tribe. Since then I have supported them as if they were my own blood. My 30 years with Indians have been the best time of my long life.

Me: It must feel an incredible honor to have won the trust of and be adopted into the Shawnee nation. I read Allan Eckert’s book, The Frontiersmen, before I came to find Panther in the Sky. It struck me, after reading both books, that they are essentially the same story told from opposing perspectives. Eckert looks at the opening of the Ohio Valley through the eyes of the white settlers and the amazing men like Simon Kenton and Daniel Boone. You view it through the lens of the Native Americans like Tecumseh and his family. Was it your intention to provide a direct counter-perspective like that or did it just happen naturally?

Thom: I had been an Eckert fan for years, and had believed his assertion that everything he wrote was true though told in novel form. As I did my own research about the same people and events, I began to realize that he had often put his own author’s slant on the story. Tecumseh and Simon Kenton had a few encounters, but weren’t all that important in each other’s lives. It was William Henry Harrison, not Kenton, who was Tecumseh’s nemesis. Eckert had disdained interviewing Indians, and thus missed some important underlying truths. He and I never met until a few weeks before his death. By then he knew from my books that I was onto him, as were many historians. But out of respect for his powerful storytelling, I stayed away from any mention of those differences, and we had a genial, mutually respectful last meeting. (I discuss details of our respective interpretations in the “Credibility” chapter of my historical-writing textbook, which was published before he died, but didn’t identify him by name.)

Me: I love the story of Tecumseh’s coming of age ritual in gaining his “pa-wa-ka stone” and I borrowed from your version of that story in Panther in the Sky to tell a similar tale of a fictional Indian boy in my own book. I think we all have some moment in our lives where we have our own, figurative, pa-wa-ka experience. Do you agree? If so, can you remember when you gained your own pa-wa-ka?

Thom: I had no single pa-wa-ka ritual or token gained in a particular moment. The equivalent developed in my upbringing by an Army officer father and his idea of self-discipline as a high virtue. I and my peers designed our own tests of physical toughness and courage to overcome our fears. Ultimately, I guess, the Marine Corps emblem became my version of a pa-wa-ka stone.

Me: Before we leave the topic of some of your earlier work, the two books we’ve discussed thus far were turned into movies. I have seen them both and found that, of the two, Tecumseh The Last Warrior, the movie based on Panther in the Sky, was the more effective movie in staying true to the book. I have shown portions of that movie in my classes and it has been well received. The movie version of Follow the River, to me, didn’t seem to capture the intensity of the story that the book did. I was curious what your thoughts are about these two film adaptations of your work.

Thom: I’ve only once watched the Hallmark TV movie of Follow the River. That was enough. Hundreds of my readers complained that the film lacked any nitty-gritty. I can compensate for my disappointment by rationalizing that millions of people watch TV who don’t read books, and they did get that inspirational story in their own way. The Tecumseh film made by Ted Turner started well, looking into the tribal ways and values as they shaped the young warrior. I managed to get our tribal chief hired on as a cultural and historical consultant for the film, and without him it could have been awful. But a series of accidents and unforeseen casting problems used up so much of the movie budget that the film stinted on the War of 1812 — which was the conflict in which Tecumseh was at his greatest.

Me: Your most recent book, Fire in the Water, centers around a tragic event, the explosion of the steamboat SULTANA in the days immediately following the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. That turned out to be the biggest maritime disaster in U.S. history, killing more than the TITANIC yet, most…including myself, were largely unfamiliar with it since the story got buried by the death of the president. How did you learn of this story and why did you decide to tell it?

Thom: I don’t know when I first learned of the SULTANA. Two things eventually directed me to consider it for a novel: My ancestors in the Civil War, and my years of experience as historical lecturer on cruises of the Delta Queen line. My great grandfather was in Andersonville, so I was aware that most of the SULTANA victims had already survived that prison. By the time the Civil War sesquicentennial loomed, I had created the character Paddy Quinn, and realized that he, as a Harper’s Weekly correspondent, should provide the main point of view, and his assignment to Lincoln’s funeral provided the subplot. I had always been daunted by the scope and complexity of the Civil War, and my limited knowledge of it, but here was a Civil War coda that I thought I could handle.

Me: I particularly enjoyed the comic relief you used as a way to break up the otherwise somber story. There were some legitimate laugh out loud moments sprinkled throughout that served to break the tension one feels while reading about such tragic circumstances. I have noticed that you use this kind of humor in many of your stories. Do you find that to be a particularly important element?

Thom: Thanks for commenting on the use of humor in the midst of all the horror. It was done not just for the reader’s relief but also because humor is often the survival kit of people in desperate circumstances, especially in soldiering. Bill Mauldin and Kurt Vonnegut showed that so well in World War II. And when drinking enters the scene, the desperate joking can rise to a sort of giddiness. As for the Civil War, there was such rueful humor as the designation of fleas and lice as “bodyguards,” and those songs the Union soldiers composed about Southern women’s urine being used to make Rebel gunpowder.

Me: After having just finished reading Fire in the Water, I have one more question for you from a writer’s perspective. I noticed that you chose to use the present tense in the narration throughout the story. I found this to be an interesting choice, but very effective. I wonder how/why you went about choosing that technique? This seems like a departure for you. I wonder, was it a decision based on anything in particular or just a whim?

Thom: This was the first time I’ve written a book in present tense, and I did it very deliberately, to increase the sense of immediacy. I do everything I can to put my reader in the moment. I believe that in this story, at least, it enhanced that sense. (Past tense inherently places the reader’s conscious “after the moment,” even though it’s the normal way of writing narrative.) I did worry about readers’ reaction to it now and then. But during that time I happened to read Wolf Hall, that wonderful novel about Cromwell and Henry the Eighth, all in present tense, and saw that it can indeed be more effective.

Me: As a history teacher, I am always looking for ways to engage my students and “hook” them on history. I think historical fiction can be a great tool for that. That is a primary reason I wrote my book. What are your thoughts on using historical fictions as a resource in history classes?

Thom: Historical novels can be valuable as supplemental reading in school courses, because even a student who abhors “History” can get so caught up in the human aspects of a well-told story that he (or she) will learn some of that history. It’s for that reason that I don’t take liberties with the real history. What they learn from me I want to be correct. Teachers say they

assign my books because they can trust the history in them. In some of my novels, I try to reveal historical angles that have been left out of the textbooks, or presented wrongly, because I know that some of the themes suppressed in the official history texts are the main part of the truth. I hear from many history teachers that those fresh angles are what they value most. Good teachers want their students to read and think critically and make their own value judgments. So in my own little way, I’m following the wisdom of my friend and mentor, the late Howard Zinn, whose historical writing countered the feel-good propaganda that is such a big part of official textbook curriculum. I am especially gratified when I hear that some of my books are assigned as supplemental reading not just in history, but also in English and literature courses. That lets me suppose that not just the history but the writing is good.

Me: It is extremely gratifying for me to hear your thoughts about that because they mirror my own views as a teacher and writer, 100%. I am also extremely grateful to you for giving me your time and providing such thoughtful answers to these questions. I think a lot of teachers and writers will love to read this…I hope it finds a good audience.

One final question to wrap things up. You informed me the other day that you are working on your next novel now. You said that it is a story involving Indians that you had started many years ago and had put aside, only to pick back up recently to set out to finish it. Can you tell us a little more about what we can expect from this new book?

Thom: The novel I’m returning to, after too many years writing about palefaces, is titled The Bones of a Hopeful Indian. It is not strictly a historical novel, as it deals with the native concept of Time, being a circle of past, present and future, not a straight line forward from hour to hour and century to century. Many famous American Indians will appear in the novel, within or without their mortal flesh.

Me: Well, James, I, and a multitude of other readers of your work, will be anxiously awaiting your new book! I thank you again for your time.