Last night I had the privilege of seeing Selma, which chronicles the marches and demonstrations led by Martin Luther King Jr. that led to the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. The movie starts off with King’s acceptance speech for the Nobel Peace Prize. As he speaks, the camera cuts away to four girls walking down the staircase of a church. They’re dressed in their finest, chatting about hair. One of them stops, grinning, to theorize about how to achieve a certain hairstyle. If you know your history, you know what happens next–and that knowledge only makes the event all the more terrible to witness.

Last night I had the privilege of seeing Selma, which chronicles the marches and demonstrations led by Martin Luther King Jr. that led to the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. The movie starts off with King’s acceptance speech for the Nobel Peace Prize. As he speaks, the camera cuts away to four girls walking down the staircase of a church. They’re dressed in their finest, chatting about hair. One of them stops, grinning, to theorize about how to achieve a certain hairstyle. If you know your history, you know what happens next–and that knowledge only makes the event all the more terrible to witness.

This brutal opening sets the tenor for the rest of the film. We see the demonstrations from ground zero: billy clubs bloodying faces, skulls hitting pavement. This movie is medicine for anyone for whom resistance movements are abstract concepts that happen “somewhere else.” The story demonstrates the fierceness of oppressed communities’ need for justice, and the corresponding ferociousness of the ruling class’s response. For anyone wondering what the big deal is about Ferguson and the grand jury decisions, Selma is a crucial reality check.

The timing of the film is nothing short of magical–and I mean that not in the feel-good sense of the word, but rather in the sense of big power that has the potential to change reality. It is impossible not to see the parallels between the Civil Rights movement and the current struggles against police brutality. In one scene, King and his colleagues rail against the white men who kill Black men with no accountability whatsoever. In another, a peaceful protester is shot to death by a cop, who walks away with no consequences. If you saw some of the dialogue in Selma in an article covering Ferguson, you wouldn’t blink. (Of course, the film also throws into sharp relief the continual erosions to the Voting Rights Act, especially 2013’s Supreme Court decision.)

The film also highlights some of the particulars of social justice work, including the planning, arguments, and dilemmas that happen behind the scenes. White allies are criticized for only showing up when crises reach a breaking point (point taken, I thought in the theater). We gain some insight into King’s tactics, including his careful–and sometimes deeply unpopular–decisions regarding when to send people into harm’s way and when to keep them from danger.

For me personally, the most powerful and disturbing aspect of the film was not only the hatred it so effectively depicted, but the hatred it provoked in me. The actors playing George Wallace, Jim Clark, and the army of cops and militant good ol’ boys did a great job of portraying these characters as utter pieces of human garbage. Perhaps their one-dimensionality is a flaw in the film, but perhaps it demonstrates the way hatred saps the humanity of the oppressor. Perhaps, for white viewers, seeing how we look through the eyes of the oppressed is a sorely needed antidote for the bubble of privilege. In any case, it didn’t take long for me to hate these men. Oh, I wanted to smack them. I wanted to kick them and spit on them. When they brought their clubs—some wrapped in barbed wire—down on human flesh, I fantasized about their arms falling off mid-swing. Reader, I wanted them dead.

One could argue that this aspect of the film demonstrates that social unrest isn’t born when a group holds a sit-in or closes down a freeway; social unrest is born when white people, confronted with the fact that Black people are human, behave like rabid dogs. However, more than that, my emotional reaction reinforced the absolute necessity of nonviolence and compassion. As King and countless other organizers have said, violence and hate only breed more violence and hate; the only way to stop the cycle is to be courageous enough to recognize your enemy’s humanity.

But the flipside, in the film, of the grotesqueness of the white oppressors is the awe and beauty of the protestors. Thanks to some savvy cinematography and genuinely breathtaking images, the marches and actions made me swell with hope and pride as the marches’ numbers swelled in the film.

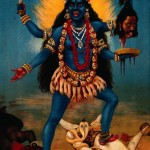

A while ago I caught some flak because I suggested that a war goddess might advocate nonviolence. Let me be absolutely clear: violence may win some battles, but ONLY a commitment to nonviolence can bring about real, authentic change. Any warrior worth their salt will pay attention to what works in the long term, not what feels satisfying in the short term. Yes, sometimes armed resistance is necessary; my own ancestors used it against the Nazis. Yes, Malcolm X was an important strategic counterpart to King–but even he started to come around to nonviolence before he was murdered. And if anyone reading this is still under the misapprehension that nonviolence is some kind of wimpy passivity, all you need to do is witness the incredible strength and bravery of the clergy and laypeople who marched, peacefully, across the Edmund Pitter Bridge and into the waiting swarm of armed police.

Selma opened last week as a limited release, and will open nationwide on January 9. Be there. Big magic is happening.