A Reading from the Book of Exodus.

There an angel of the LORD appeared to Moses in fire flaming out of a bush. As he looked on, he was surprised to see that the bush, though on fire, was not consumed. So Moses decided, “I must go over to look at this remarkable sight, and see why the bush is not burned.” When the LORD saw him coming over to look at it more closely, God called out to him from the bush, “Moses! Moses!” He answered, “Here I am.” God said, “Come no nearer! Remove the sandals from your feet, for the place where you stand is holy ground.

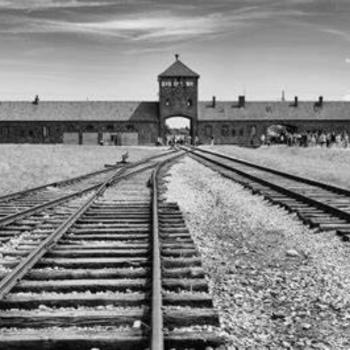

“Images you’ll get use to while grieving your lost child:

Crackers, fruits and meats in little gift boxes.

Oranges peeled, never eaten.

Your spouse on the ground.

You on the ground.”

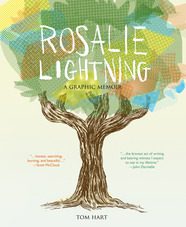

I discovered Tom Hart’s graphic memoir, Rosalie Lightning, in my local indie bookstore last weekend. I was drawn to the cover art and the blurb by John Darnielle of The Mountain Goats:

“…the bravest act of writing and bearing witness I expect to see in my lifetime.”

Bearing witness to what? I wondered. I opened the cover and saw on the first page a black and white rendering of a scene from My Neighbor Totoro, one of my daughter’s favorite movies, and knew right away from the color and the tone of the image and text that the author had lost his child.

I read the first half of Hart’s story standing right there at the table in the bookstore, transfixed by the unadorned prose and how the images, drawn and arranged in cells, communicated meaning like a dream, flickering between past, present, and future, juxtaposing the impossible with the all too real. I’ve never seen a piece of art that so closely recreated the experience of grief.

I bought a copy so I could read the rest at home, not so much because I wanted to cry–though I did–but because I felt like I had entered into something so private that it seemed wrong to do it in public. It felt like confession, like prayer, like revelation.

Hart’s daughter, Rosalie Lightning, died suddenly in her sleep before her second birthday. Her death was unexpected, unexplained, “like a bomb going off.”

“…’Rosalie Lightning?’ Who gives a baby that name? No small number of our friends commented on her coming and going like lightning. What the hell were we thinking?”

The nightmarish days after her death are full of this kind of wonder–had he and his wife missed the signs of her departure? Not just symptoms of an undiagnosed illness–there weren’t any–but the portents and foreshadowing of a story, a myth, a poem? Hart’s drawings reel through dreams and memories and imaginings of the days before and after her death. Sometimes the cells are black. Sometimes entire pages are black. Those are the moments when he loses his battle to make sense of things, to achieve any kind of congruity in a world that has suddenly toppled off its axis. He closes his eyes. His mind goes dark. The book goes dark.

Rosalie Lightning is terribly sad, and I did often have to set it aside and cry, really cry, for the loss of this child in the world and for the pain of her parents. Rosalie is so real on these pages. Hart recreates her speech and vision and imagination. He captures all the delight and tenderness of new parenthood, and reminds us of how a baby makes the world new and full of possibility. One of the great surprises of having a child was how it set the broken places in me so they felt they might actually work again–work better than ever. In motherhood I felt suddenly expansive, capable of infinite love. All that wonder is here on Hart’s pages, right alongside the “capacious hole” that Rosalie’s death has opened, the dark void we sense from page one that nothing and nobody can fill.

Why would I choose to read such a sad book on a Sunday afternoon? And read it hungrily, gratefully? Why, when I closed the cover after reading the last page, did I hold it to my chest as if it were almost a living thing I could love? As if it were Rosalie herself, not lost to the capacious void after all? Hart doesn’t merely immortalize his daughter with his art–that wouldn’t be nearly so surprising. With his art, he shows how she still lives. Even when I closed the book the whole world seemed charged with her presence.

When I read the Old Testament reading for this weekend, the story of God speaking to Moses from the burning bush, I thought again of Rosalie Lightning, and I realized that I’d wanted to read the book alone, in silence, not just because it was private and hit all my raw nerves, but because I sensed that by entering the author’s grief I’d found myself on holy ground. The book felt like a prayer that grows from lamentation to praise.

Near the end there’s a full-page rendering of two characters in a boat, a recurring image throughout. One of them says, “Maybe when I die and I’m floating above it all, I can say I lived through the most horrible thing I feared most.” It sounds and looks devastating, but it’s a turning point.

This is Hart’s acknowledgement, in sadness, in resignation, that he is going to survive his daughter’s death. He has been badly burned, maimed, disfigured, but not consumed.

And this is why Rosalie Lightning is not, in the end, merely tragic. It is beautifully, whole-heartedly pro-life. Pro-her life. Hart ends where he began, with My Neighbor Totoro, with the acorns Rosalie collected growing into tall, strong mature trees. He ends with the hard facts: There is a girl named Rosalie Lightning, who once “vomited and pooped and ate noodles” and “loved watercolors” and “drew on walls.” She was once right here, eating and drawing with her father, and one day she disappeared without warning, but she is not nowhere. She seems instead to be–sometimes infuriatingly–everywhere.

The book ends with one word, repeated on multiple pages. YES.

I understand why Darnielle called Hart’s book an act of bearing witness. Who makes a better witness than the one who suffers the incomprehensible and lives to tell the tale? The one who walks out of his tomb?

Where the fire rages but doesn’t destroy, this is holy ground.