(1) (Re)birth

I am waiting. I am waiting in a waiting room. I am waiting in a waiting room until the event which I am waiting for happens and begins.

One year, I am looking at a drip. A bag of Bleomycin hooked up to my port. The time it takes to enter my body is five hours. The time it takes for my cancer to remit is seven months.

Another year, I am looking at a light. A blinking, red light. It scans my body to check for abnormalities, for growths. I feel stuck in the tube of the CT machine, myself a trapped pea in an unlikely pod. The time it takes to look inside of my chest is ten minutes. The amount of visits I make to the machine seem infinite.

The next year, I am looking at a monitor. A fetal heartbeat monitor. The time it takes for my body, an anxious vessel, to make something whole and perfect is nine months and seven days. The time it takes for my baby to be born is 18 hours.

The moment my daughter was thrust toward me by the doctor, all slippery and wonderful and screaming, was the single most intense, emotional rush I’ve ever had. Something had grown inside of me that was right. Utterly, exquisitely right. Her confused and perfect face looked at me and I was reborn with her. I was her birth witness, and she mine. Everything that had happened outside of that moment faded away–the months of waiting and worrying, the pains of labor, my husband Peter’s exhausted and concerned face. I am overrun with vitality; her alertness gives me an overwhelming sense of buoyancy and light. Pure and righteous, we were both (re)delivered into the world.

We name her after my grandmother, June. She was due in June and born in July.

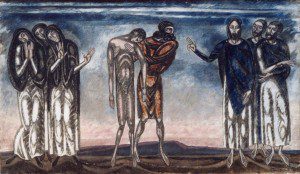

(2) Body as Tomb

June’s birth was so unlike the last time something had grown inside of me, a cancer four years prior. Both experiences had involved a swelling of the body–one a disease, the latter a condition. Morals were assigned: one growth not normal, one growth very normal. Unnatural, Natural.

My body had done wrong before–betrayed itself, myself with cancer. I had turned against me.

The baby had kicked hard in those last months to be sure, but cancer had blasted my bones and flesh from the inside. Or no, that was the medicine, chemo for seven months. Cancer was silent, mostly invisible.

Both states involved a mental and physical countdown to the main events of remission and birth. Emotionally, the states could not have been more different. During my treatment, I was a stone wall. Nothing upset me. I was doing what I had to. If I wasn’t calm and composed, then who would be? The tough, thick skin grew on me, forcing my hair to fall out.

Others treated me like a cracked porcelain cup, or an endangered animal. I couldn’t stand the condolence cards, the “Thinking of You” sentiments bounced out of my mailbox and into the trash can.

Throughout pregnancy, however, I was fraught with worry, depression, and panic. Now I really was a fragile object, an animal on the brink, protecting my unborn young. Others seemed so convinced that everything would be fine, that my baby would be born healthy. Where others saw assured hope and happiness, I found myself walking on nine months worth of eggshells.

My pregnancy had been very medicalized. I was treated as high risk because of my past with cancer and chemotherapy. Nine months, ten growth checks via 3D ultrasounds in which my daughter appeared as a small clay doll, rolling and growing as Peter and I let out sighs of reliefs with each “Everything looks great.”

I struggled with post-partum depression and anxiety after June’s birth. It was both similar to and completely unlike the post traumatic stress disorder I was diagnosed with after chemotherapy ended. After the baby was born last year, I transformed from a growing, pure body with two lives inside, glowing and expectant and anxious and hopeful. I emerged from her birth a different, deflated tomb, mourning the loss of it’s treasure.

After chemotherapy ended and I was in remission, I missed my cancer. With cancer, I was fighting something, had an enemy, was on a roadtrip with a clear destination. Without cancer, I was doing none of those things. I could not return to the self I had been before getting sick. Being cut free from the identity of being a continual patient was so discombobulating- not unlike the ending of pregnancy and the entry into motherhood leaving me off-balance, in the dark.

(3) Lost and Found Again

The purity in June’s face is the wrinkle forming in my brow. She gives me back youth and ages me. Looking at her is such happiness that I could die. I wonder if bringing forth a new life is a solution to one’s own assured death; a continuation of the line as immortality. There is so much comfort in knowing she will be here after I am gone. If we begin dying from the moment we are born, did I stop dying the moment I gave birth? Have I risen from the dead, or been put back into a blissful sleep? I will take both.

There are two B.C.s in my self: Before Cancer and Before Child. In each case, I was found before and lost after. In each case, I was lost before and found after. Both umbilical cords still exist in my heart and head.

Megan Hildebrandt is an artist, educator, cancer survivor and arts-in-health advocate. She currently teaches Painting and Digital Media at Interlochen Center for the Arts. She’s working on a graphic novel, Tunnel Visions, about being treated for cancer at age 25.

Megan Hildebrandt is an artist, educator, cancer survivor and arts-in-health advocate. She currently teaches Painting and Digital Media at Interlochen Center for the Arts. She’s working on a graphic novel, Tunnel Visions, about being treated for cancer at age 25.

This piece originally appeared on the blog The Lymphoma Letters, where you can also read a Q&A with the artist about cancer, PTSD, pregnancy, and parenthood.