Last month, I attended Mass at the border; I was part of a community of believers uniting around bread and wine miraculously made into flesh and blood.

I was on the Mexican side, sitting on a concrete street curb next to another Catholic sister. Together we were a color pop in the assembly: we stuck out in our bright turquoise T-shirts declaring “Catholic Sisters for Compassionate Immigration Reform.” Nearby sat our friend, Br. David, a Franciscan Capuchin, bearing witness in his dusty brown habit. Guests to this area, this Mass we were attending coincided with the events of the School of Americas Watch Border Convergence throughout the entire weekend.

We were among a crowd of a couple hundred other folks. Some sat upon haphazard rows of folding chairs, others leaned against fences and buildings, many stood. We were gathered on a crumbling, uneven street formed from a mishmash of concrete, asphalt and sandy earth. In front of us was a simple stage, where a humble bishop vested up in plain view and a folding table transformed into an altar. A giant wooden crucifix leaned against the platform, wounds facing toward us.

Behind us, Ingenieros street formed a T-intersection where it met up with Calle Internacional, a dusty gray road that ran along the tall, steel, rust-colored fence, the fence that created an arbitrary line between two nations.

During his greetings at the start of Mass, the presider, the Bishop of Nogales, Sonora, Mexico—José Leopoldo González González—acknowledged the people who were praying with us from the U.S. side of the fence. At the sound of his words, many heads turned and gazed upward, where the fence ascended from a hill, just in time to see hands poking through the 3-inch cracks, waving fiercely, glad for the connection. Other hands, clasped together in prayer right through the fence, seemed to bob like a nod.

“We are united as one, we are all the body of Christ and in the body of Christ there are no borders,” the bishop proclaimed. Hands clapped in agreement, with gratitude.

* * *

Earlier in the day I learned the story of the horror that had put us all in this particular place, the reason why we were having mass on a street in Mexico on a Saturday night. On the corner, at that T-intersection, a memorial cross was cemented into the sidewalk below a wall layered with gray and white plaster and paint. The wall’s layers could not shield all the bullet holes that had been filled with stucco.

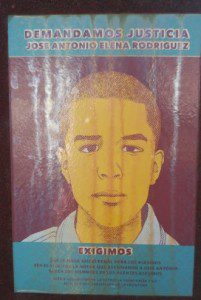

This Mass on the street was a vigil memorial for José Antonio Elena Rodríguez, a 16- year-old boy who was shot by U.S. Border Patrol agent, Lonnie Swartz, four years ago, in 2012. The cross in the concrete marked the place where he had been shot 10 times, after supposedly throwing a rock at the fence—although even that is unlikely.

Certainly, on the night he was killed, José Antonio carried nothing other than a cell phone as he walked to meet his brother after playing basketball. Even though he may have gotten caught up in a skirmish between U.S. Border Patrol and Nogales cartels, he had not committed a crime. He was a victim of the terrible cliché–in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Even four years later, José Antonio’s family experiences no consolation of justice from the U.S. government. Their attempts to sue and bring the Border Patrol to trial were dismissed; they were told they had no rights under the U.S. constitution since they were not U.S. citizens. I learned later that at the time of the memorial mass their case was awaiting a chance to be appealed.

* * *

During the Mass, I thought a lot about blood. My stomach turned as I imagined Jose Antonio’s blood pouring out on that street corner. I pondered the wine turned into blood on that folding-table altar. I was aware that all the bodies in this street pulsed with the same red liquid. I felt the ache of my own wounds, the need to replace the bandage on my own knee, bloodied and bruised from an embarrassing fall on the uneven sidewalk earlier that day.

Bread becomes flesh and wine becomes blood in every Mass, but this took on new meaning for me when the sacrifice was offered near the site of a murder, when those who had gathered in love were also broken bodies.

I prayed with a consciousness that José Antonio’s story of abuse by U.S. Border patrol against the innocent and in-need, as awful as it was, was one case among many. I knew that the U.S. Border Patrol had killed dozens of folks on the other side of that fence without due process. I was aware that many migrants, including children, were unjustly detained in for-profit prisons; where many people have died by suicide or neglect or lack of access to basic health care. I knew the issue of immigration was complex and contentious, but the call to heal the wounds in the broken body of human community was very straightforward: all of us are sacred and made in God’s image and likeness, everyone must be revered as an image of God. Praying on that street, my heart ached with misery, aware of the too many ways we, as humans, were failing at upholding the commandment.

Yet, it was one of those types of masses that made me so proud to be Catholic, so happy that I am part of a truly universal, borderless Church. I was touched by the extension of hospitality from our Mexican hosts to gringos like me, how they made sure we each had water bottles, and a Mexican woman offered choppy English translations of the Bishop’s loving words.

I was glad to be part of a Church that takes stands on complex issues and advocates and cares for the “little ones,” the anawim, just like Jesus showed us how to do when he walked earth in the midst of a violent empire. I knew that it could be risky for me to stand with and for such people, but through the graces provided at liturgies like these, I’d have the strength to do so; shedding our blood and tears for the sake of others is what we’re called to do.

* * *

I follow the sister and brother near me away from the curb, as we move through the wavering line toward the altar. We sing and hold our hands reverently in front of us as we move. We bow and utter “Amen,” put bread in our mouth, chew. We swallow, consuming a broken piece of bread, the body that we all are: through each act we affirm “yes” we are broken, we are this body, we are one. By our acts and presence, we manifest St. Augustine’s ancient instructions, “Be what you see, receive what you are.”

I return to my spot on the curb, renewed and gratified. I am also concerned. I turn to my friend, the sister at my side, “Do you think anyone brought communion to the people on the other side of the fence?” If so, I wonder what border patrol would do, for it is apparently illegal to pass anything through the fence.

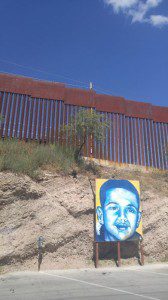

During the closing hymn the bishop makes his way off the stage, through the crowd, and toward the place where José Antonio was shot and killed. Two priests and José Antonio’s family are at his side. He holds a simple white styrofoam cup. He speaks prayers and blessings in Spanish, then sprinkles the memorial cross with holy water from the simple vessel. We cross the street, approaching the wall, to stand under a new, yellow and blue mural of José Antonio’s face, blessing the painting, sprinkling the lively image of a young body with holy, renewing water. We pray for justice for José Antonio and for peace along the border.

* * *

A few weeks after that unordinary communion of the Body of Christ, I was far away from the border in northern Wisconsin, working on house chores on a quiet Saturday. I listened to the radio as I moved houseplants around and dusted, as I unwound the vacuum cleaner’s long cord. Suddenly I froze in place, listening carefully when I realized that the reporter was speaking about Jose Antonio’s murder. I learned that an appeals court in San Francisco was considering whether his grandmother being a legal permanent resident of the United States was enough of a link for his family to be protected by the U.S. constitution. I also learned that the Border Patrol agent, Swartz, who had killed José Antonio, is in fact facing a murder charge in Arizona.

Things were not yet resolved; the broken body not mended. Yet, any move toward justice is a gesture in the right direction—if only a bandage on a still-bleeding wound.

On staff at Marywood Franciscan Spirituality Center in northern Wisconsin, Julia Walsh is a Franciscan Sister of Perpetual Adoration, a Catholic youth minister, a committed social justice activist, and a student at Catholic Theological Union. Her writing has appeared in Global Sisters Report, Living Faith, U.S. Catholic, and Off The Page. Visit her online at messyjesusbusiness.com and @juliafspa on Twitter.