“They said there’ll be snow at Christmas. They said there’ll be peace on Earth. But instead it just kept on raining. A veil of tears for the virgin birth.”

So sings Greg Lake, disaffected by Christmas—and he’s not alone. A season so touched by light makes me even more aware of the depth of the darkness around us–“the people who walked in darkness have indeed seen a great light” (Isaiah 9:2). The contrast can be unbearable.

Even the secular world senses it. Even left with the paper-thin shadow of an absent faith marked by the dregs of a secular season, the world can still see, if not the hope of Christmas, at least the truth that there is something to be disappointed about.

Greg Lake’s song may not be particularly good, but it’s a cry of pain emerging from a long tradition of Christmas mourning, whether sacred or secular, kitschy or profound. Dickens saw ghosts, Elvis had a blue Christmas, and we all have our Grinchy moments. When we recall the hearty “Good King Wenceslaus,” we often forget that he was eventually martyred for trying to be a good Christian ruler.

Speaking of martyrs, what of Christianity? What does Christianity have to say about sadness at Christmas? Must it say what so many would have it say, that if we would only rediscover the “true meaning” of Christmas the darkness would just go away? That all we need is to put Christ back in Christmas?

Our faith is deeper–and our forebears in the faith wiser–than this.

First, let’s not underestimate the Church calendar, that Scripture-inflected wisdom passed on to us to help us to remember the right things at the right times, and to draw us into the redemption of time itself. And what we find when we look to the Church calendar is that the ostensible innovation of a hard, realistic, disenchanted perspective on Christmas is not in fact a modern innovation—before the world got there, the Church was there first.

Before modernity, there was Advent, and it was good.

It was good because it was sober. The typical Christmas response to the kind of disappointment we see in Lake’s lyrics is to get drunk so we can forget about the whole thing. It’s certainly a film cliché; we all remember Mel Gibson in Lethal Weapon. But Christianity is more daring. Christianity insists we remain sober while looking darkness in the face. Traditionally, this is what Advent is—a time of fasting and asceticism and looking reality–death–in the face.

Advent sermons often, rightly, focus on the four last things: death, judgment, heaven, and hell. A promotional poster at one Church I attended featured a large skull, staring out at me like Yorick in Hamlet. This is entirely consistent with Christian tradition, which celebrates Advent as a time of preparation for Christ’s coming; the season of Advent awaiting His first coming also points toward His second coming, for which Christians are to be prepared.

But now to the narrative itself. The elements are familiar enough: a child is born in Bethlehem, and his parents know he is born for something special. He will grow up to serve the Lord, YHWH, the God who was there at the Exodus. And then something happens.

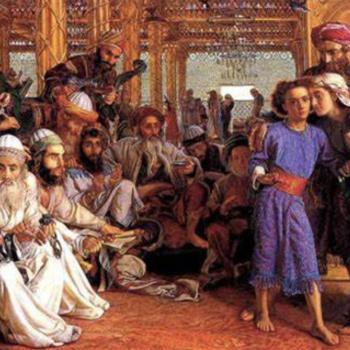

Throughout Bethlehem and the vicinity, soldiers knock on doors, sent by King Herod, who has become obsessed with rumors of some rival toddler king. These parents know the story of Moses, how he was kept safe in a basket from the infanticidal Pharaoh. But theirs is not the story of Moses. There is not even time for shock. The soldiers swiftly kill the child and move on. And every year, against the backdrop of this story, we blissfully sing, “To us a Child is born/to us a Son is given.”

Because, of course, this child—the one who was killed—is not the One we are singing about. The Child we are thinking of has been safely transported to Egypt, His parents having been warned in a dream of Herod’s plot. But back in Bethlehem, countless other sons—helpless children—are dead.

How can this be good news? How can we sing these songs? Is the kingdom of God just another game of thrones? What kind of faith can be perverse enough to have such a story as its backdrop? What kind of miracle would it take to redeem such a story? Those angels appear to the shepherds, singing, “Glory to God in the highest, and on earth peace, good will toward men.” Can we, in good conscience, sing with them?

There is a cry, and that cry is recognized in Scripture. The cry is Rachel, weeping for her children, and refusing to be comforted because they are no more (Jeremiah 31:15, Matthew 2:18). Her cry echoes throughout Scripture–a cry for lost sons and daughters. It is the cry of Job for his children. It is the cry of David for his lost sons—the one who rebelled, the one who died in infancy, and the one who turned to idolatry. It is the obscure and often-overlooked cry of Rizpah when her sons are handed over to the Gibeonites. It is the crying of Jairus for his daughter, and, yes, the tears of Abraham as he raises his knife to slay his son, his flesh and blood, on the altar. It is the weeping of Eve for Cain and Abel. It is YHWH weeping for His child, Israel; it is the Creator weeping over Adam.

God Himself is weeping—can there be comfort for Rachel?

But then the narrative takes an unexpected turn. The Messiah, Christ, does not grow up to become a force equal and opposite to the Herods, Pilates, and Caesars—rulers who build kingdoms to hide the blood of their many innocent victims. Jesus’ protection in Egypt is not simply an act of nepotism for a favorite son. No, He is protected in Egypt because the suffering reserved for him is greater. The weeping of Rachel must be answered, and He will answer with His blood.

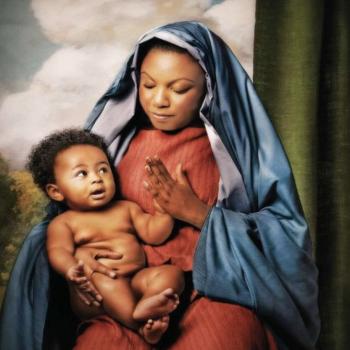

The tender moments with His mother at the manger will eventually turn to that excruciating moment when He turns to her, shamed, naked, and contorted, and says to the beloved John—and to us also—“Behold your mother.” And we do. We look and find, here at the heart of history, Jesus’ mother, aching with the pain of a sword-pierced soul. And Rachel continues to weep. And Mary weeps, because the Child she treasured in her heart is no more. Or so it seems. For in her Son, death—the thing that we, with Rachel, weep over—is overcome.

And indeed, how could Rachel be answered otherwise? What mother would be satisfied with anything less than the unworking of her child’s death? Rachel refuses to be comforted, because comfort is not what she wants. She does not want comfort; she wants her children.

There is a wise rabbinic tradition that suggests that Job’s children are not doubled like the rest of his possessions at the end of the book bearing his name because children are not possessions. You can’t pay off the death of children simply by giving someone double the amount of children. As a solution, the rabbinic tradition suggests Job’s children were literally resurrected, but there is another possibility. Job is only given seven more sons and three daughters at the end of his calamities because God has in fact doubled his children, but in an unexpected way: half of them are not with him in this world; they are awaiting the resurrection of the dead and the life of the world to come.

And we, with Job, wait—still with the tears of Rachel—for the end of time, when every tear will be wiped away. That time is not yet come, and so there are still tears. There are tears, and it is Christmas. But this—this hope—is why we sing. Not because there is no suffering, not because there is no Rachel, not because there are no slaughtered innocents, whose blood indeed cries out in their feast during the season of Christmas. No, it is not because these things are not, but because He—Christ—is, and He has done what is impossible, even more impossible than the alchemist’s trick of turning lead into gold.

He is shaking, but it is no longer with mourning. He has turned mourning into mirth, death into life.

But not yet—at least not for those of us still bound by this world of fallen history. For now, we can only wait, continuing to weep for pain and sing for joy, until we discover behind them the common ground of both.

Amen, come, Lord Jesus.

***

The Coventry Carol also remembers the murdered sons of Bethlehem that we remember in today’s Feast of Holy Innocents. On Christmas Day 1940, the BBC broadcast the carol from the ruins of Coventry Cathedral, bombed in the blitz.

Karl Persson is a scholar of premodern literature and theology, and is a professor in the Literature and Language Departments at Signum University. He’s a regular contributor to the Patheos Catholic Channel’s Inner Room, a blog focused on contemplative spirituality and the recovery of ancient Christian practices and social imaginaries.

This essay originally appeared, in a different form, as “The Shadow of Christmas” in The Canadian Lutheran.