I begin with two facts:

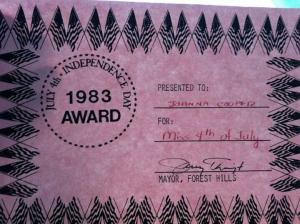

In 1983, when I was 12, I was named Miss Fourth of July in a parade in my grandmother’s neighborhood in a small, historic town in North Carolina.

After the Civil War, virulent racists in government invoked the image of the purity and innocence of white womanhood as reason for stripping African Americans of their rights as citizens, fomenting sexualized racial anxiety and calling for control of “savage” blackness in the name of “our women.”

How are these facts related? Why am I thinking about them today?

My usual personal narrative around my reign as Miss Fourth of July has more akin to the 1989 movie Miss Firecracker with Holly Hunter, in which a scrappy orphan tries to win out against the more genteel elements in her southern town, though in my case the waifish orphan actually won the title. And in my case, it wasn’t a beauty pageant, just me rollerskating around the neighborhood in a children’s parade. And I wasn’t trying to win anything. I just wanted to be part of the gang.

But I’m thinking this year of the costs of celebrating white girlhood, white womanhood. I was a cute kid, ok? When I was little, I thought I was the Sunbeam bread girl—a pretty little white girl in a large ad on the side of a building in Salisbury, NC with upswept blond hair, eating a piece of white bread with butter. My uncle told me that was me. (It turns out the model for the ad was an aunt of someone I later went to grad school with in Philadelphia.) And despite some murky mystery surrounding my origins, my mother’s side of the family always went out of their way to let me know I was part of the gang, and that our family had something special, despite it all. Some sparkle, some wit. Yes, even beauty.

But being a scrappy Miss Fourth of July only gets you so far. What boundaries do you agree to stay within when you accept the title? And celebrations of the little blond girl as icon are sadly problematic, as Toni Morrison so profoundly explores in The Bluest Eye. My memory of the event and my joke of posting my certificate on Facebook every Fourth is tainted now by a cultural climate in which the rhetoric of “our women” as being worthy of protection against invading dark-skinned criminals is once again being spouted by those in even the highest office.

The kind adults in my grandmother’s neighborhood in 1983 who looked at a scrappy kid who spent a lot of time at her grandmother’s house and decided to give her a certificate for adding some cheer to a national holiday … they weren’t thinking of The Bluest Eye or of issues of “national purity” and psychosexual anxiety. They weren’t. They were being nice. But right now, white women need to take every opportunity to say, “I stand with other women. I stand with the dignity of all human beings. Not in my name. Never again in my name.”

Joanna Penn Cooper is a poet and essayist and author of The Itinerant Girl’s Guide to Self-Hypnosis and What Is a Domicile. She curates the “Approaching Mystery” series for Sick Pilgrim, publishing flash essays by writers encountering the unseen, the uncanny, and the unresolvable. She lives in Durham, NC.