“Can you comment on the self as grotesque?”

The men on the panel at the conference looked bewildered, but the woman knew exactly what the questioner meant. Is experiencing one’s body as strange, even as grotesque, just part of being a woman?

Later many of us shared our stories–tales of embarrassment and horror over what our bodies can do, can make, can shed. Each of us had them. Each of us nodded in agreement and empathy as the others spoke.

Almost all those stories revolved around menstruation and childbirth. Getting your period, not getting your period. Having babies, being unable to have babies. Choosing to forego pregnancy for whatever reason, choosing the have ten babies for whatever reason. Why the taboo, the stigma, the shame, even now? I would have said because we were Catholic, but not all of us shared the same religious heritage.

It does seem strange to me, though, given our attribution of heavenly queenship of the saints to a human mother, Mary of Nazareth, that we should all be so ashamed of what our bodies can do, when surely her body did the same. (Though a quick search of the sentence “Did Mary menstruate?” will produce all sorts of bizarre theological argument for and against.) My own experience of Mary as a lifelong Catholic was not as a real woman, a woman who bleeds, but as a cold stone statue wreathed in fake flowers. No wonder I never connected with her.

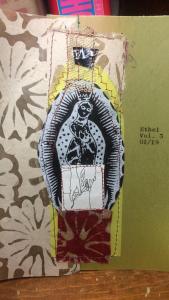

I considered the question again when I received the cover image of Ethel Zine, where I recently contributed. The image roundly shocked the group of women in which it was shared–Christians, agnostics, churched and unchurched.

But why?

Menstruating women see the diagram overlaying the image of Mary as the Virgin of Guadalupe every time they open a box of tampons. I remember studying that image for hours even before I started my period, finding it mysterious and even titillating, though I had all the same parts depicted. And yet, when I finally started my period, I still couldn’t figure out how to insert a tampon. I left the plastic applicator in for four hours before I gave up, thinking the problem must be with me.

For so much of my life, my own body was a mystery to me. When I gave birth, the nurse asked if I wanted to watch the baby crown, and I recoiled. I’d never held a mirror up to myself before. I couldn’t bear to look.

What might it have meant to me to have grown up with images of Mary like these? How might it have changed my experience of menstruation, childbirth?

To connect the workings of my body to the workings of a woman’s body deemed sacred, holy, adored?

There is a tradition of Maria Lactans, or the lactating Virgin, but Lord knows I never saw them in school or church or anywhere at all, until I was a nursing mother and a nun pulled me aside at an art show to show me an example. Still, these images are often sexualized and just flat-out anatomically bizarre, not representative of any human woman’s experience. And perhaps that was the point.

The truth is the images of Mary created by Sara Lefsyk and Sara Star, though they may be initially shocking in their newness to me–Catholics remove Mary to the pedestal and protestants largely ignore her for fear of Mariolatry–make me love Mary a little more. Hell, they make me love me a little more.

Meditating on these images of Mary not just as maiden or mother but as woman, I find myself less grotesque. I can imagine my body as other than a site of pain, shame, or even mystery or titillation. I can’t go so far as to say I imagine myself as potentially holy or adored or even powerful, but there’s a gift in seeing your own body, and Mary’s, as less strange.