“What about the self as the grotesque?. What happens when that category is applied to ourselves, as opposed to when we apply it to something other? What happens when we begin to see ourselves as the other?”

These questions that really struck me when I heard them. They’ve stayed with me, partly because of the way I experience myself. As someone who is extremely introverted I’m used to seeing myself from the outside, feeling like I’m outside the group, or out of place. There is a sense of self-alienation that goes along with feeling alienated from other people.

But the other aspect of this question that really struck me was the way in which it played into questions about gender. I was initially reluctant to make the claim that it is a gendered thing to see oneself and one’s body as grotesque or as strange. It seems like there are a lot of factors that could lead to this sense.

But the thing that kept happening when I talked to people about this idea was that women immediately and universally knew what I was talking about when I talked about seeing oneself and one’s body as terra incognita. I barely had to explain the concept to them. They knew. They had their own examples of times that they felt alienated from their bodies, and their examples always included things that are unique to women’s bodies – menstruation, childbirth, gender specific illnesses.

This happened across the ideological spectrum. It wasn’t just self proclaimed feminists who identified with this theme. One woman (who absolutely would never describe herself as a feminist) got very heated when she pointed out that women live with feelings of self-alienation every day and no one takes it seriously, but that when a man writes about himself as the grotesque, it is considered great art. Franz Kafka may write about a man who wakes up to discover that he is a bug and call it The Metamorphosis, but, for women, sometimes that’s just called ‘waking up.’

As I said, the women got it. But the men generally didn’t. Talking about this theme with men generally led to blank stares. Guys tended to have a lot of questions about what precisely women felt alienated about. What exactly was it that was unknown about our bodies? Can we really say that our bodies are always changing when we have a menstrual cycle? A cycle is predictable, after all. And so on.

The conversations I’ve had lead me to think that experiencing oneself and one’s body as strange and grotesque is just part of having a woman’s body.

To some extent our attitude towards our own bodies is surely influenced by our cultural context and attitudes. But to what extent, if any, is our experience simply a reaction to the bare facts about female biology? Maybe part of having a cyclical body is just that you always feel a little strange because your body is always changing? Maybe part of being a body that menstruates is just that blood is gross and so you’re a little gross?

***

These were the thoughts that were rattling around in my brain at the Convivium conference. One question that arose in the panel on women’s bodies was “What practices or ideas or writers are restorative for women? What helps us move beyond this sense of alienation, and what helps us to accept our bodies and experience a sense of integration with our bodies instead of separation?”

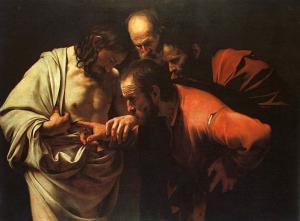

Jessica wrote about how art can challenge this sense of alienation, particularly art that might shock our sensibilities. The disgust or discomfort that marks our reaction to certain images might make us ask why we have this reaction. We might find that an image that shocks actually reveals something alarming about the attitudes and assumptions we have about our own bodies.

Story is another space in which we can move away from this attitude towards ourselves. Through story, and through conversation, we can explore and tease out the things that are taken for granted in our own attitudes. A friend pointed out that a story about a dog stealing a steak from a counter is very different from a story about a dog pulling a used maxi-pad out of the bathroom garbage can.

Another friend related that a seminarian friend had told her that he had been advised, in seminary, to always keep a table between himself and any women he happened to be alone with.

There is something “extra” about women in the cultural imagination, and this is uncovered through shared stories. It isn’t just about blood and the way we respond to biological realities. When we make the choice to prioritize our own stories, to speak and write about them, it can be healing.

I believe that all this is true, and yet these questions about the body and about healing have been exacerbated for me by something that someone said at the conference: What about the sense of our bodies as being strange and wondrous?

This question stumped me. So much so that I couldn’t even really grasp the significance of the question for several days. Strange and wondrous instead of strange and grotesque? I couldn’t begin to imagine what she meant.

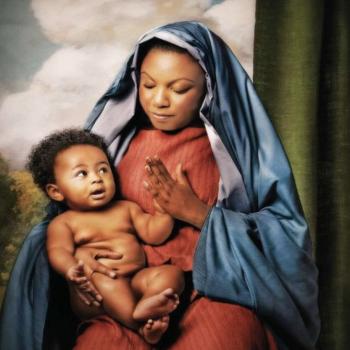

That isn’t strictly true. I’m familiar with a sort of hagiography of women’s bodies when it comes to motherhood. Motherhood is strange and wondrous. Pregnancy is a sort of holy mystery. Women have a special gift in their ability to bring new life to the world. All these things may be true, and yet, women are not always pregnant. Women do not always become mothers. Being female is a larger category than being a mother.

What was so fascinating to me about the question about our bodies being strange and wondrous, was that it was clear that the question did not refer to ideals surrounding motherhood. There was a recognition that pregnancy and motherhood are not the same thing as being-in-a-female-body. And yet, the argument was that there is something wondrous there, something strange, something holy.

A new question has arisen for me. What would a restoration of women’s relationship to our bodies look like? Will it involve accepting ourselves as normal, and renegotiating our idea of “normal?” Or will we always see ourselves as a little strange, but learn to see that as something wondrous, and not as something grotesque?

This question seems particularly relevant as we begin Advent. We are in a season that anticipates and celebrates the Incarnation. We reflect on God-made-man. We acknowledge that God has a human body. And yet, we haven’t really come to terms with the weirdness of our own embodied nature. We worship a God who became like us, and yet in taking on our flesh, he took on something that we ourselves have yet to understand. Gnosticism is a tempting heresy because it tells us what we already believe – that our bodies are gross or wrong or broken. Like my friend at Convivium, the Incarnation challenges me to examine how I think about bodies – women’s bodies, my own body. We often say that through the Incarnation, Christ took on our mortal grossness. Perhaps this is looking at things the wrong way round. We could also say that the Incarnation reveals something about our bodies that we did not know: that bodies are to be a site of the wondrous, of the holy. Even women’s bodies.