NCR: Have you seen the film?

Neeson: Yes, twice in fact.

What did you think of it?

When you’ve worked on a film and see it for the first time, there’s a lot going on in your mind: what they used, what they cut, didn’t use, a whole medley of things. When I saw it the second time I was really taken in. It was a meditation on doubt, faith, a serious study about belief, a real meditation on faith. I left the cinema with questions, and some of the scenes have just stayed with me.

How many times have you played a priest?

Let’s see, the first time was for a British Irish film called “Lamb” based on a novel by Bernard MacLaverty in 1985 and “The Mission,” of course, in 1986. [His character Priest Vallon in Scorsese’s 2002 “Gangs of New York” is not really a priest but the leader of a Catholic gang.]

What did acting in “Silence” mean to you? Had you read the book before?

I had read the book, but I had found the translation flat and it was hard to finish. It was only when I read Jay [Cocks] and Marty’s script that the story came alive.

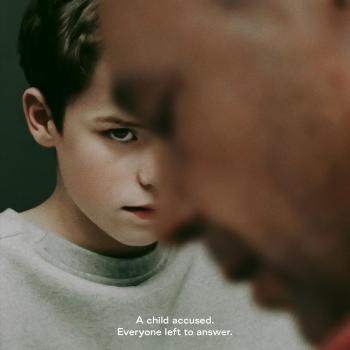

What was it like to play a priest who would be considered by the church to have caused scandal and committed sin?

You know, the Lord works in mysterious ways. Early on, while preparing, I thought about the Jesuits, the priesthood, their training, and how God can be packaged very neatly in an organized way and issues can be very back and white. But the world is many shades of gray. One thing that I did learn, something that I try to apply always is what Fr. Dan Berrigan taught me when we were filming “The Mission.” We became pals at that time, and as you know, he died last year.

That lesson was and is “to see God in all things.” It is a part of Jesuit training and it opened my mind in so many ways. I am still filled with doubt at times. And I come back to what Father Dan taught me, to see God in all things, in the good, the bad, the nasty, the brutal. I think this was the real test for Fr. Ferreira in “Silence.” It is not clear in the film, but I think he had his faith when he died.

My last line in the film is, “I doubt it,” when Rodrigues said to me, “You just said, ‘Our Lord.’ ” I talked with Marty about that scene. Should I indicate to the audience I am very aware of what I said and that I know that you know that I know? Should I communicate with some subtlety here? In the end it is as you can see and judge for yourself.

How was Christ working through Ferreira?

We have to bear in mind that we did not live through Stalin’s Russia. You couldn’t trust anyone, your mother, father or children. You never knew if they’d tell the authorities if you were doing something religious. This was kind of similar to what was happening in Japan at the time of the events in the film.

Christ was working through Ferreira in a very dangerous time.

From my research, Ferreira was a very learned man, he knew medicine and astronomy and he was a philosopher. Part of his decision to apostatize, I think, was that he believed that Christ would work through him and this gave him the freedom to learn the language and to serve the people in other ways that were meaningful.

What do you think his idea of God was?

The Jesuit training, through the Spiritual Exercises, is very profound. You strike up a relationship with Christ through the Gospels, so that ultimately Christ becomes your brother, someone you talk to regularly, every day, throughout the day. We see it happening with Rodrigues, this prayer, but God is not returning his calls. Only in the silence does he hear Christ’s voice: “I am still with you. …”

I think Ferreira had gone through something similar, lonely nights of thinking, “What should I do?” They tortured him for five hours, hanging upside down over a pit. Some of the Japanese Christians lasted for days.

I think Ferreira’s idea of God was ultimately one of love, but this is what I choose to believe myself. If God were a stern master, I would have given up the faith long ago. God is love, love is God. I have had personal experiences of God’s love, beautiful and calming, all the things the Psalms talk about. If he was a stern master, well, I don’t know.