"He who fights with monsters should look to it that he himself does not become a monster."

— Friedrich Nietzche in "Beyond Good and Evil"

Take Back the Media draws our attention to these Ten Commandments yard signs by Georgia artist Bill Fisher.

The signs, if you look closely, actually list "Ten of the Commandments of the Geneva Convention[s]." Specifically, it lists some of the rights and protections afforded prisoners of war.

That's all the signs do. They make no accusations. They point no fingers. They simply list the rules.

The signs' Ten Commandments imagery — two stone tablets and all — is all the argument it provides for the legitimacy of those rules. The Geneva Conventions have the force of law, embodied in international treaties which are echoed in turn in American law. Fisher's Decalogue imagery suggests a deeper legitimacy, that such rights are, in Jefferson's phrase, entitlements of "the Laws of Nature and of Nature's God."

Yet despite their lack of accusation and argument, the signs seem to provoke an angry, defensive response. A print out of this sign hanging at my desk at work prompted one co-worker to hang in its place a lengthy description of Saddam Hussein's atrocities.

Curious. How did we get to the point where a list of atrocities could be viewed as a rebuttal of the Geneva Conventions?

My co-worker suggested I was promoting "moral relativism." This is, of course, exactly what the sign with its Ten Commandments imagery is arguing against. If you're looking for moral relativism, check out Beijing's argument that human rights are a "Western construct." Or, for another variant, check out the following, from the e-mail my co-worker sent:

… you cannot apply moral relativism to this debate. We ARE the "good guys" and the terrorists (and Saddam's cronies) ARE the bad guys. It does not diminish my regard for our higher moral standing as Americans that we occasionally go astray …

I don't want to pick on my friend here, but I think the gut reaction he is expressing is typical and widespread, and therefore worthy of attention.

In the same breath he both condemns and advocates a "moral relativism" — the idea that to be "good" merely involves being better than the bad guys.

I suspect that what he's really responding to is a perceived accusation of what used to be called, back during the Cold War, "moral equivalence."

This old argument occurred in a polarized world in which every country was accounted either one of ours or one of theirs. "They" were, of course, the bad guys — the Soviets — and make no mistake, they were very, very bad. Yet in opposing them, we found ourselves with some rather unseemly friends — people like Ferdinand Marcos in The Philippines, Mobutu Sese Seko in Zaire, Gen. Pinochet in Chile, a string of genocidal generals in Guatemala and, in Iraq, a brutal dictator named Saddam Hussein.

Yes, some folks did argue that these odious alliances meant that there could be no moral distinction between the United States and the "evil empire" of the Soviet world. But the vast majority of us who were concerned about human rights were not arguing "moral equivalence" — we were simply arguing that the evilness of the evil empire did not excuse our own bad behavior or our own tacit or explicit support for regimes like Saddam's or Pinochet's that routinely violated basic human rights.

There is a sense, however, in which I do believe in a kind of moral equivalence. I believe that the moral obligation to respect and protect basic human rights weighs equally on all people and all regimes everywhere. This includes the obligation to follow the spirit and the letter of the Geneva Conventions. Any failure, by anyone anywhere, to meet this obligation is simply wrong and must be condemned.

Does that mean — or even suggest — that all such failures are equivalent and equally evil? Of course not. Uday Hussein and his father committed horrors within the walls of Abu Ghraib that its current apologists for torture never dreamed of.

But what is the point of such statements other than an attempt to excuse our own bad behavior simply because others have behaved much worse? What is there to be proud of in the claim that we are morally superior to Uday Hussein?

Scratch any complaint about "moral equivalence" and you will find, just below the surface, the advocacy of evil means — of torture, murder and lawlessness — in the supposed defense of the good.

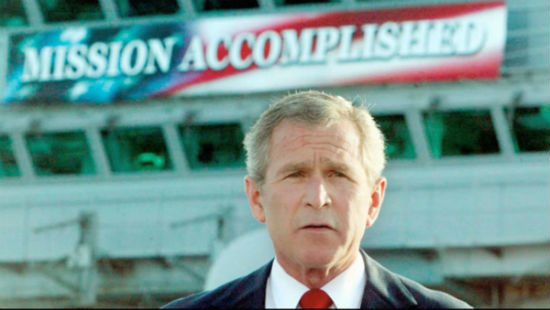

The Abu Ghraib scandal puts America at a crossroads. My co-worker's visceral response — shaped by the trauma of 9/11, by the Bush administration's manipulation of it and their deliberate conflation of all "evildoers" from bin Laden, to Saddam, to al-Sadr — is, I fear, likely to win the day. The rationalization of evil in opposition to a greater evil (real or imagined) seems like the only way for many Americans to retain their necessary self-image as "the good guys." That path is sloped, and the slope is slippery.

The alternative, I believe, is to remind Americans of, and to recommit America to, an idea of the good that involves more than simply being slightly better than the worst people we can think of. This will involve, among other things, rejecting the notion that the Geneva Conventions are a "quaint" nuisance and instead championing them as an international embodiment of the democratic principles at the core of the idea of America.