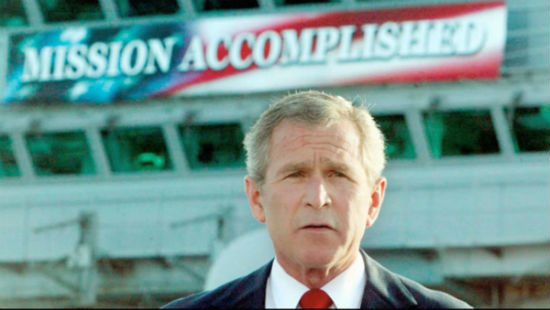

In a guest editorial last week at Dr. Cole's place, William R. Polk takes an unflinching look at the reality-based options remaining in Iraq.

Polk is not campaigning for office, so he doesn't need to gloss over the situation in order to appear "optimistic":

Iraq is in a terrible condition, its society has been torn apart, scores of thousands have been killed and even more wounded, its infrastructure has been shattered, dreadful hatreds have been generated. Today, there are no good options — only better or worse alternatives.

Polk sees three possible courses: 1) "staying the course;" 2) "Vietnamization;" and 3) "to choose to get out rather than being forced."

Option No. 3 is often described/caricatured as "cut and run." This phrase has proved remarkably effective as the ace that trumps all other argument. Most of the staged "debates" on cable news have ended when this card was played:

Talking Head 1: … any responsible military engagement needs to have some idea of what constitutes victory. There needs to be an exit plan …

TH2: But we can't just cut and run, of course. Surely you're not suggesting we just cut and run?

TH1: No, no, no. Of course not. We can't just cut and run.

TH2: These aren't the droids you're looking for.

TH1: These aren't the droids we're looking for. We can't just cut and run. Exit strategies are for cowards who hate America.

Behind the distorting caricature of "we can't just cut and run" are several ideas and principles that give the slogan its power.

Some of these ideas are expressed as bits of folk wisdom, like the "Pottery-Barn Rule," which says that if you break it, you bought it (i.e., you must pay whatever it takes to restore it to wholeness). Or like the Boy Scout rule, which says that good scouts must leave a campsite in better condition than it was when they arrived.

Most compelling to me is the argument that Iraq must not be allowed to become a "failed state." Failed states constitute a threat to their neighbors and, ultimately, to America and the rest of the world.

Chaotic failed states can result in intolerable humanitarian situations and ethnic slaughter — as occurred in Somalia, the former Yugoslavia and Rwanda during the 1990s. The worst-case scenario I most fear in Iraq is a replay of the genocidal Rwandan civil war. Iraq's Sunnis have, like the Tutsis of Rwanda, enjoyed and abused decades of privilege despite their minority status. Iraq's Shiite majority — and the Kurdish minority, a majority in the north — are as legitimately aggrieved as the Hutus, but they're far better armed. And lurking across the border is not Burundi, but Iran.

In addition to such humanitarian crises, failed states also create lawless havens for terrorist networks like al-Qaida. One of the many bitter ironies of the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq has been the self-fulfilling prophecy regarding that country as a base for al-Qaida operatives. The network couldn't gain a toehold in that country before the invasion, but now it has become for them a haven, a base of international operations, a source of weapons, explosives and recruits.

"'We' can't just cut and run" is, in part, shorthand for "'we' must not allow Iraq to descend into the chaos of a failed state."

To an extent, I agree, but this assumption involves some question-begging. It presumes that the core question — what is the most likely way, now, to prevent Iraq from becoming a failed state? — is already answered, and the presumptive answer is "to stay the course and not cut and run." And all of this presumptive question-begging allows us to avoid considering that "the course" upon which we are staying remains ill-defined and may, in fact, lead in due course to the very outcome we are hoping to avoid.

Polk is not optimistic that "staying the course" can produce a good outcome in Iraq. He argues that "the course" leads, rather, to a worst-case scenario:

The first option has been called "staying the course." In practice that means continued fighting. France "stayed the course" in Algeria in the 1950s as America did in Vietnam in the 1960s and as the Israelis are now doing in occupied Palestine. It has never worked anywhere. In Algeria, the French employed over three times as many troops, nearly half a million, to fight roughly the same number of insurgents as America is now fighting in Iraq. They lost. America had half a million soldiers in Vietnam and gave up. After forty years of warfare against the Palestinians, the Israelis have achieved neither peace nor security.

Wars of national "self-determination," to use President Woodrow Wilson's evocative phrase, can last for generations or even centuries. Britain tried to beat down (or even exterminate) the Irish for nearly 900 years, from shortly after the 11th-century Norman invasion until 1921; the French fought the Algerians from 1831 until 1962; both Imperial and Communist Russia have been fighting the Chechens since about 1731. Putin's Russia is still at it. There was no light at the end of those "tunnels."

The first exception that occurred to me to Polk's categorical statement — "it has never worked anywhere" — is the United States' experience in the Philippines during the early 20th century. America "stayed the course" in the Philippines and was able to establish a degree of security and order. The "course" that we took there, however, involved concentration camps, forced relocation, collective punishment and torture.

Polk does not mention the Philippines, but he does account for the consequences of such an approach:

It is not only the actual casualties that count. What wars of "national liberation" have taught us is that they brutalize the participants who survive. Inevitably such wars are vicious. Both sides commit atrocities. In their campaigns to drive away those they regard as their oppressors, terrorists/freedom fighters seek to make their opponents conclude that staying is unacceptably expensive and, since they do not have the means to fight conventional wars, they often pick targets that will produce dramatic and painful results. Irish, Jewish, Vietnamese, Tamil, Chechen, Basque and others blew up hotels, cinemas, bus stations and/or apartment houses. …

Faced with such challenges, the occupying power often reacts with massive attacks aimed at terrorists but inevitably also killing many civilians. To get information from those it manages to capture, it also frequently engages in torture. Torture did not begin at the Abu Ghraib prison; it is endemic in guerrilla warfare. Two phrases from the Franco-Algerian war of the 1950s-1960s tell it all and ring true today: "torture is to guerrilla war what the machine gun was to trench warfare in the First World War" and "torture is the cancer of democracy." Guerrilla warfare and counter insurgency inexorably corrupt the very causes for which soldiers and insurgents fight.

Almost worse, even in exhausted "defeat" for the one and heady "victory" for the other, they leave behind a chaos that spawns warlords, gangsters and thugs as is today so evident in Chechnya and Afghanistan. After half a century, Algeria has still not recovered from the trauma of its war of liberation against France.

The longer the war in Iraq continues the more it will resemble the statement the Roman historian Tacitus attributed to the contemporary guerrilla leader of the Britons. The Romans, he said, "create a desolation and call it peace."

Read Polk's entire argument. It's a persuasive case that staying the course in Iraq will cost thousands more American and Iraqi lives, and billions more dollars, but that the end result will be a desolation that no one will call peace.