Nobel Peace Prize winner Shirin Ebadi and Hadi Ghaemi of Human Rights Watch write today in The New York Times offering "The Human Rights Case Against Attacking Iran."

Much of their argument regards the particular situation in contemporary Iran, but the essence of their case rests on a core principle that transcends those particularities:

Respect for human rights in any country must spring forth through the will of the people and as part of a genuine democratic process. Such respect can never be imposed by foreign military might and coercion — an approach that abounds in contradictions. Not only would a foreign invasion of Iran vitiate popular support for human rights activism, but by destroying civilian lives, institutions and infrastructure, war would also usher in chaos and instability. Respect for human rights is likely to be among the first casualties.

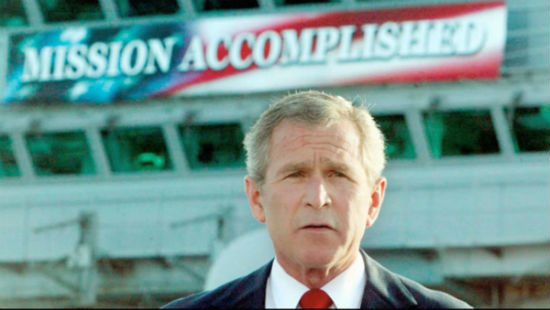

That argument should sound familiar to readers of this blog, as it closely parallels my arguments here in what might be called "The human rights case against invading Iraq."

One school of thought holds that Ebadi and Ghaemi are rendered irrelevant by the recent impressive turnout in the election in Iraq. Adherents of this school believe that this election, and the courage demonstrated by the Iraqi voters, is proof that respect for human rights can be — and, in fact, ought to be — imposed by foreign military might and coercion.

Some would go even further, suggesting that anyone who agrees with Ebadi and Ghaemi is merely "justifying the maintenance of oppression." (The Medium Lobster provides an acute summary of this perspective.)

It strikes me as a bit unseemly to suggest that the courage displayed by Iraqi voters exists because of, rather than in spite of, the occupation. As Charlie Pierce puts it, "You do not own their courage."

Slate's Fred Kaplan sounds a similar note: "Yes, as President Bush said in his address this afternoon, the Iraqi people showed the world they want freedom. But this has never been in doubt."

What has been in doubt was whether they would be able to reach that freedom after a chaos-inviting invasion and a chaos-creating botched occupation. I share with Kaplan the post-election hope that the Iraqi people might be able to forge something like a free country out of the mess we've created. And I appreciate that the authors of that chaos share this hope — desperately.

It is a bit hard to reconcile all this post-election triumphalism and talk of flowering democracy with the continued espousal of the "flypaper" theory. President Bush reiterated his commitment to making Iraq a magnet for terrorists in his recent State of the Union address: "Our men and women in uniform are fighting terrorists in Iraq, so we do not have to face them here at home."

So America is committed to a stable and democratic Iraq, but wants simultaneously to ensure that Baghdad remains a bloody battleground that distracts terrorists who might otherwise be attacking our "homeland." This only makes sense if you believe that A) there exists only a finite and nonrenewable number of terrorists, and B) the best way to make the world a better place is to Kill All the Bad People.

Shirin Ebadi and Hadi Ghaemi want to see a free, democratic Iran that respects human rights. They want this desperately and urgently. They want this as desperately and urgently as the people of Iraq wanted to be freed from the tyranny of Saddam Hussein.

Yet they also believe that some cures can prove worse than the disease. Shock therapy (or shock-and-awe therapy) tends to kill the patient as well as the cancer.

"The arc of the universe is long, but it bends toward justice." We can — and ought, and must — help the people of Iran travel that arc, and the steps that Ebadi and Ghaemi suggest are important. But they are right to argue that "foreign military might and coercion" are not a promising short cut on the path to democracy, freedom and human rights.

Like everyone else, I do not know how to get from the current state of affairs in Iraq to anything like the hoped-for outcome President Bush described: "A country that is democratic, representative of all its people, at peace with its neighbors, and able to defend itself."

And like everyone else, I watched the elections last month and caught a glimmer of hope that the people of Iraq might still yet work a miracle and bring about that which foreign military might and coercion could never hope to achieve.