Shankar Vendantam is a stupid, lazy amnesiac, which is to say a reporter for The Washington Post.

Vendantam covers the "human behavior" beat, writing Monday about the "hindsight bias." That's actually an interesting phenomenon, and Vendantam has some useful things to say about its affects and implications for things like juries and eyewitnesses. But anything constructive in Vendantam's piece is overwhelmed by the wretched opening paragraphs, which serve only to make people less well informed than they were before they picked up The Post:

Antiwar liberals last week got to savor the four most satisfying words in the English language: "I told you so."

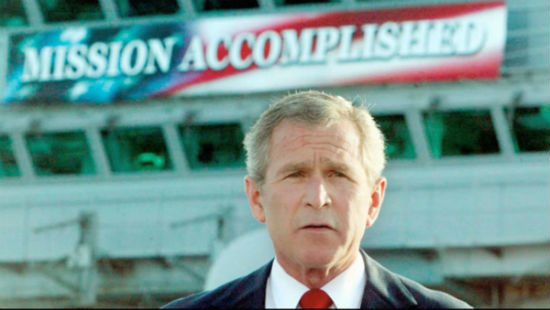

This was after a declassified National Intelligence Estimate asserted that the war in Iraq was creating more terrorists than it was eliminating. For millions of people who opposed President Bush's mission in Iraq from the start, this was proof positive that they had been right all along. Yes, they told themselves, we saw this disaster coming.

Only . . . that isn't quite true.

One of the most systematic errors in human perception is what psychologists call hindsight bias — the feeling, after an event happens, that we knew all along it was going to happen. Across a wide spectrum of issues, from politics to the vagaries of the stock market, experiments show that once people know something, they readily believe they knew it all along.

This is lazy and stupid. (Sorry too repeat that, but I read something like this and I get a little dumbstruck, so to speak, like a tourist standing on the rim of the Grand Canyon unable to say anything for the first 10 minutes other than, "Big. It's so big.")

Vendantam makes a huge, and hugely inaccurate, dismissive generalization, unsupported by a single concrete example or statistic. It's positively Jenkinsian.

Vendantam starts to get it wrong with the first two words — "Antiwar liberals" — implying that the invasion and occupation of Iraq had only ever been opposed by lefty hippie types and not also by paleoconservatives, realists, Niebuhrians, Kennanites, Pope Benedict and the College of Cardinals, and gung ho, hoo-ah military types like Richard Clarke and David Hackworth.

Oh, and also by millions of people all over the world who marched in the largest mass demonstrations ever seen in the history of planet earth. Those millions of people, not all of them liberals, held signs, chanted slogans, made speeches, gave interviews and wrote letters to the editor. And many of them — millions of them — predicted exactly what Vendantam says they could not have predicted.

It's not like we're talking about something shrouded in the mists of ancient history, some event from the dawn of time. We're talking about 2002 and early 2003. Most people, unlike Vendantam, can still remember what was and wasn't said 3-4 years ago, but even if your memories have grown fuzzy, there's a paper trail, and a video trail, and a pixel trail. Vendantam could've walked down the hall to his colleague Walter Pincus' office, where the senior reporter could have shown him stacks of articles and notebooks filled with quotations from people who said exactly what Vendantam says they only think they said due to "hindsight bias." Or Vendantam could have called CNN and asked to borrow the hours and hours of videotape from all of, say, Kenneth Pollack's scores of appearances on the network during 2002 and early 2003. Pollack often appeared in a "debate" format on CNN. Those people he was debating? They were right and he was wrong. And they said exactly the sorts of things that Vendantam imagines they only imagined having said.

Or, of course, Vendantam could have simply used Google to find the hundreds of thousands of articles and blog posts from the distant past of four years ago in which thousands of different people said exactly what Vendantam says no one ever said.

There's a bit of back-pedaling qualification later, as Vendantam changes the standards:

This is not to say that no one predicted the war in Iraq would go badly, or that the insurgency would last so long. Many did. But where people might once have called such scenarios possible, or even likely, many will now be certain that they had known for sure that this was the only possible outcome.

The goal post here is shifted dramatically. Vendantam starts by saying that no one "saw this coming," and here shifts to no one saw this as "the only possible outcome."

Here is further evidence that Vendantam doesn't have a clue about the subject. "The only possible outcome" was never the language of those who opposed this calamitous misadventure. That tunnel-vision certainty was the language of its proponents. The opponents of this war spoke instead in terms of probabilities, of what was likely, almost always with the caveat "I hope and pray that I'm wrong."

Vendantam never heard, never listened to, our initial and ongoing opposition to this war. Anyone who did so would realize that none of those millions who predicted exactly this lethally disastrous outcome now finds a shred of satisfaction in having been proved right.

If Vendantam wants a psychology reporter's angle on this matter, here's one worth exploring: Why is it that the people who weren't foolishly, disastrously wrong four years ago and now, by virtue of having been right all along, disqualified from participating in the debate on how to resolve this FUBARpocalyptic fiasco?