Satire is traditionally the weapon of the powerless against the powerful. I only aim at the powerful. When satire is aimed at the powerless, it is not only cruel — it's vulgar.

— Molly Ivins

This Sandy Huffaker cartoon is, at best, a case of collateral damage.

At first glance, it seems to take aim at Hollywood and the vapidity of so many movie releases, but the sub-Mad Magazine level film titles on the marquee don't pack much of a punch. ("Laffs About Nothing" — is that supposed to be bad?) So the real target here seems to be the audience, represented by the cruelly drawn figures in the corner. The cartoon's most vicious contempt isn't directed at the purveyors of dreck, but at the consumers on whom they inflict this stuff.

This is a stumbling point for many critics of pop culture — whether of the movies, or television, Top 40 radio or mass market fiction. All of these seem like easy targets, but it's trickier than it looks because there are too many innocent people in the way to get off a clean shot. The critic who sets out to say that TV is stupid and crass winds up arguing that TV viewers are stupid and crass. The critic who opens his mouth to call romance novels silly and unworthy closes his mouth having called all the women who read them silly and unworthy.

And that's not cool. First of all, it's not a very winsome approach to persuading others to accept whatever point it is you're trying to make. "You're an idiot," is rarely a useful starting point if you're trying to get the other person to listen to the rest of what you have to say. The result of this approach, as in the cartoon, is a sneering elitism.

Let me be clear about that word, "elitism." There's nothing wrong with having high standards for popular art and popular entertainment, standards that help you (and others) to separate the good stuff from the inferior. But when those standards are turned against the audience, when they're used to separate the good people from the supposedly inferior, that's when the critic loses my respect and attention. That's when the critic loses everybody's attention. This is what makes such critics truly elitist — the tiny circle of people still listening to them is, indeed, an exclusive elite.

Such critics also, perversely, end up siding with those they initially set out to criticize because they reinforce the dreck-merchants' standard fall-back defense, "We're just giving the audience what they want."

The main problem here, though, is that such critics are blaming the victim. That's just wrong. Someone who has been tricked into paying good money for a Clay Aiken CD has suffered enough. There's no need to add insult to injury.

Which brings us to Joe Bageant's essay on the World's Worst Books, "What the 'Left Behind' Series Really Means."

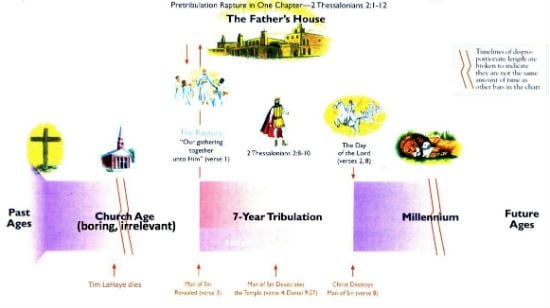

Much of Bageant's essay is fun, an entertainingly and appropriately horrified reaction to a series of books that fails on every level (except sales). I've pointed out a few of those books' shortcomings myself, and for the most part I agree with this aspect of Bageant's jeremiad. He's right to point out that these books are more than just shoddy entertainments, that they are dangerous and damaging propaganda. And he's particularly on the money in discussing Tim LaHaye and Jerry Jenkins' unseemly delight in the fictional suffering and death of those who disagree with them, as well as their bizzarre belief that this fictional vindication provides some real-world validation for their perspective.

So nothing Bageant writes about the books or their authors bothers me. But what he writes about their readers does.

He begins with a promising line of thought:

How can anyone acquire and hold such notions? Answer: The same way you got yours and I got mine. Conditioning. From family and school and society, but from within a different American caste than the one in which you were raised. …

Tens of millions of American fundamentalists … read and absorb the all-time best selling Left Behind book series as prophecy and fact. How could they possibly not after being conditioned all their lives to accept the End Times as the ultimate reality?

This is promising because it begins to explore the question of why these horrible books are such big sellers. Figuring out how this "conditioning" was done is an important part of figuring out how it can be undone — how these people can be rescued from that conditioning. How these readers might be, well, saved.

Bageant himself is a recovering fundamentalist. He grew up steeped in End Times-mania and "prophecy" obsession. So his own personal history ought to suggest to him that change is possible, that these "tens of millions of American fundamentalists" trapped in a warped and circumscribed worldview can be liberated from it.

But he's not interested in liberating them. He writes them off. It turns out his use of the word "caste" above was not merely an unfortunately careless accident. He means it. To Bageant, the readers of Left Behind are the Untouchables, inferiors who should be left to their own sad fate.

Here is just a sampling of the scorn heaped upon those readers, what he calls "the great unwashed tribes of the faithful ":

We are talking about a group of Americans 20% of whose children graduate from high school identifying H2O as a cable channel. Children who, like their parents and grandparents, come from that roughly half of all Americans who can approximately read, but are dysfunctionally literate to the extent they cannot grasp any textual abstraction or overall thematic content. …

Allow me to get down to the nub of this and say what urban liberals cannot allow themselves to say out loud: "Christian majority or not, the readers of such apocalyptic books as the Left Behind series are some pretty damned dumb motherfuckers caught up in their own black, vindictive fantasy."

Bageant begins his essay by quoting a 15-year-old fan of the series, who said, "The best thing about the Left Behind books is the way the non-Christians get their guts pulled out by God."

That makes Bageant angry, and he's right to be angry. But he's wrong to direct that anger at the 15-year-old kid or the millions of readers like him.

"If anyone causes one of these little ones who believe in me to sin," Jesus said, "it would be better for him to be thrown into the sea with a large millstone tied around his neck." That's angry. But the anger is directed at the proper target — at the powerful and not the powerless.

LaHaye and Jenkins are fair game. They have grown wealthy and powerful by causing the little ones who believe to sin. They deserve to have a millstone — or at least a millstone-sized book review — tied around their necks.

But their readers — these little ones — are already suffering enough. They need our pity and our patience, not our scorn.

(For a far more charitable and empathetic, and therefore more hopeful and constructive, look at this same subculture, see Christopher Hedges' "The Radical Christian Right Is Built on Suburban Despair.")