I'm not at all pleased to be linking to The American Spectator, but they've published a piece by William Tucker that's worth reading: "Iraq and Counterinsurgency."

Tucker isn't optimistic about America's prospects in Iraq:

What we have in Iraq is a series of American fortifications where soldiers live a life that reasonably mirrors conditions back home and then once a day or week put on "full battle rattle" and risk their lives by venturing into what is essentially hostile territory.

Granted we have a lot of people on our side and a sizable portion of the population wants us to stay. … But no American soldier goes anywhere in Iraq without full body armor and a humvee. Helicopter flights are made at night and under conditions of extreme secrecy. Anyone with a rifle is a potential insurgent and there are thousands of them. There is no margin of safety.

He points out that the models for the current counterinsurgency campaign "are from colonial experiences" and examines what he considers "the best analogy to Iraq," the American experience in the Philippines in the first half of the 20th century, beginning in 1898:

We were anti-colonialists … and our general public declaration was that we would soon grant the Philippines its independence.

Once in possession of the Islands, however, people began to have second thoughts. Were the Philippines really capable of governing themselves? Didn't they need some political experience? Wouldn't they benefit from the tutelage of an advanced country like the United States? Maybe we should hang on to them awhile.

President William McKinley was firmly in favor while his 1896 Democratic opponent William Jennings Bryan led the opposition. …

The "insurgency" broke out a year later when two American privates on patrol killed three Filipino soldiers in San Juan, a suburb of Manila. While Admiral Dewey had not suffered a single casualty in the Battle of Manila Bay and the whole Spanish-American War only produced 332 deaths, the counterinsurgency was much costlier.

Over the next fifteen years, 126,000 American soldiers were engaged in the conflict. A total of 4,234 died, along with 16,000 Filipino insurgents. The poorly equipped Filipinos were easily overpowered by American troops in open combat but mounted a formidable guerrilla campaign. Atrocities were committed by both sides. Estimates of civilian deaths, largely from famine and disease, ranged between 250,000 and 1,000,000.

The insurgency lasted fifteen years, on and off, even as we tried to establish civilian institutions. …

I've written about this parallel before (see "Thrilla in Manila") believing, like Tucker, that we seem to be repeating the mistakes we made 100 years ago.

But if you tune in to cable news, you'll hear near-unanimous agreement about a very different lesson from the American experience in the Philippines. There no one remembers or much cares about the 4,234 American soldiers killed, or the hundreds of thousands of dead Philippine civilians, or the way America stumbled from the ideals of the Monroe Doctrine to become, itself, an oppressive occupying colonizer. According to the Beltway sages, none of that is what's really important.

All that matters to the punditocracy is this: McKinley won the election. Bryan lost. The pointless occupation of the Philippines may have led to slaughter and may have damaged out national interest and corroded our national character, but it was good politics. If Democrats in Congress today don't listen to their advice and get with McKinley's program, they warn, they'll end up losers — just like William Jennings Bryan.

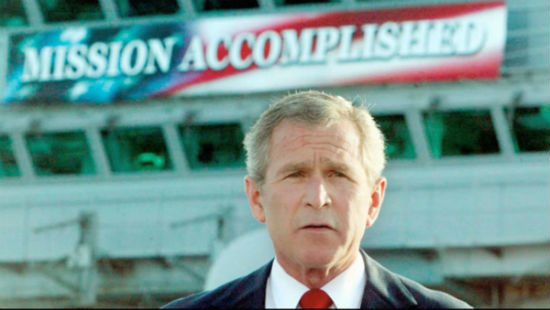

If a war is popular, they argue — and to their way of thinking, war is always popular, never mind what the people actually think — then the war is right. Even if the war is, by definition, unwinnable, you can still pretend you won, shouting down anyone who points out the truth by calling them "the party of surrender." Elections don't usually work that way. In an election, you can't just continually define-down victory until it looks just like defeat. So from the pundits' perspective, wars are easier than elections. It only makes sense then (to them) to focus on winning elections instead of avoiding wars you can't win.

If you want to know where this conventional wisdom conventionally leads, take a closer look at the American experience in the Philippines.