Attacking Iran would be Bad

So Sarah Baxter of The Sunday Times (“Pentagon ‘three-day blitz’ plan for Iran“), George Packer in The New Yorker (“Test Marketing“) and Lance Mannion (“Oh what the heck, let’s start a third war!“) all say that the Bush administration may be considering a major strike against Iran.*

That is a Very Bad Idea.

“Bad” can mean a lot of things. It can mean wicked, unjust or morally suspect, as when we refer to villains as the “bad guys.” It can mean unwise or foolish (bad bet, bad idea); broken or dysfunctional (bad sparkplug, bad title); inept (bad singer, bad fielder); erroneous (bad spelling, a bad note) or spoiled and rancid (the milk’s gone bad). I mean all of those here.

The criteria of the just war tradition provide a useful framework for illustrating why I think a potential attack on Iran would be a Very Bad Idea. Here is a useable summary of those criteria from Paragraph 2309 of the Catechism of the Catholic Church:

The strict conditions for legitimate defense by military force require rigorous consideration. The gravity of such a decision makes it subject to rigorous conditions of moral legitimacy. At one and the same time:

– the damage inflicted by the aggressor** on the nation or community of nations must be lasting, grave and certain;

– all other means of putting an end to it must have been shown to be impractical or ineffective;

– there must be serious prospects of success;

– the use of arms must not produce evils and disorders graver than the evil to be eliminated.

But so what? What does it matter what the Catholic catechism says? It’s not legally binding, nor should it be. And even if, as is the case, the idea is not exclusively Catholic or even exclusively Christian, who cares about the moralizing and hand-wringing of a bunch of philosophers and theologians off on the sidelines somewhere?

Fair questions. I appreciate that the moral considerations of the just war tradition can seem wholly irrelevant or academic. The kind of people who really want to have a war are going to have one whether or not I, or even the last two popes, tell them it would be immoral. So let’s set aside, for the moment, the moral aspect of these criteria and just consider the pragmatic contributions they may have to offer.

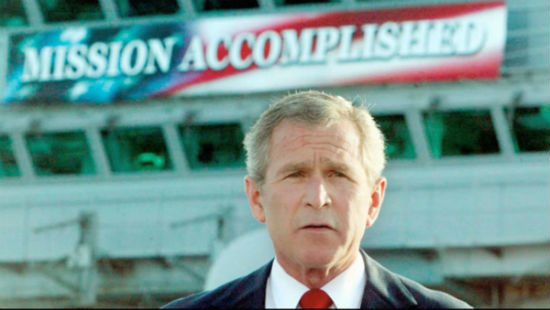

Those of us who subscribe to these criteria evaluated the proposed American-led invasion of Iraq before it happened and we found it to be, unambiguously, an unjust proposal. In terms of the version of the criteria summarized above, this war is 0-for-4.

But note in particular that final criterion above, the one usually referred to as “proportionality,” summarized here as not producing “evils and disorders graver than the evil to be eliminated.” The invasion of Iraq had no just cause, it was not a last resort and it did not suggest serious prospects of success, but to me the most important factor here was that it was disproportional — it was likely to produce “evils and disorders graver than the evil to be eliminated.” Here is what I wrote about that back on August 8, 2002:

The question of proportionality … is bound up with the question of likely outcomes. … Another way of putting these questions is this: Will this war likely make things better or worse?

Answering such a question involves more than merely applying abstract ethical principles. It involves weighing matters of fact and probability, prudence and judgement, learning from history to project our best guesses onto the future.

And my best guess is that … the “reckless, ill-conceived and possibly disastrous” manner in which the Bush administration is pursuing this effort seems likely to make things worse. That’s not a just war.

This is where, I think, the just war criteria make a pragmatic contribution. Heeding the principles of just war can keep you out of the quagmire. The reason for this is very simple: Unwinnable wars are disproportional and therefore, by definition, unjust.

So while I don’t expect the Bush administration*** to care very much that the attack against Iran it may be considering would be another 0-for-4 — that it would be unjust and immoral — I do think they should be expected to care that it would be counterproductive and unwinnable. It would “produce evils and disorders graver than” those that exist now.

I realize that Bush and Cheney aren’t terribly worried about graver evils (they think this makes them look “tough” and “manly”), but I’m desperately hoping that some of their deputies can persuade them to be concerned about graver disorders.

At the end of Packer’s New Yorker piece, he adds this postscript:

Barnett Rubin just called me. His source spoke with a neocon think-tanker who corroborated the story of the propaganda campaign and had this to say about it: “I am a Republican. I am a conservative. But I’m not a raging lunatic. This is lunatic.”

More of this, please. Fewer raging lunatics, please.

– – – – – – – – – – – –

* Baxter’s Times article mostly just indicates the existence of contingency plans, which doesn’t necessarily mean that even someone as recklessly bellicose as Dick Cheney is pondering implementing those plans. It’s also possible that all of this talk is simply clumsy saber-rattling akin to Nixon’s “Madman strategy.”

** The first criterion, usually called “just cause,” is nicely expressed here. The usual language of “defense against wrongful attack” is simply presumed as self-evident. If there is to be any possibility of a case for just war, this formulation assumes, then there must be an “aggressor.” This doesn’t necessarily mean that the good guys can never shoot first — defense against imminent wrongful attack could still be a just cause. But defense against the fear of the potentiality of the possibility of wrongful attack-related program activities doesn’t cut it.

*** My dad had a cartoon on the wall of his law office: Two cavemen are sitting on a rock and one is saying something like, “There’s no point in making a law against eating people, because the kind of people who are going to eat other people are going to do it whether or not there’s a law.”