“To abolish God!” said Gregory, opening the eyes of a fanatic. “We do not only want to upset a few despotisms and police regulations; that sort of anarchism does exist, but it is a mere branch of the Nonconformists. We dig deeper and we blow you higher. We wish to deny all those arbitrary distinctions of vice and virtue, honour and treachery, upon which mere rebels base themselves. The silly sentimentalists of the French Revolution talked of the Rights of Man! We hate Rights as we hate Wrongs. We have abolished Right and Wrong.”

— The Man Who Was Thursday, by G.K. Chesterton

Ron Suskind describes one of several smoking guns presented in his latest book, The Way of the World:

In the fall of 2003, after the world learned there were no WMD … the White House ordered the CIA to carry out a deception. The mission: create a handwritten letter, dated July, 2001, from [former Iraq Intelligence Chief Tahir Jalil Habbush] to Saddam saying that Atta trained in Iraq before the attacks and the Saddam was buying yellow cake for Niger with help from a “small team from the al-Qaida organization.”

The mission was carried out, the letter was created, popped up in Baghdad, and roiled the global newcycles in December, 2003 (conning even venerable journalists like Tom Brokaw). The mission is a statutory violation of the charter of the CIA, and amendments added in 1991, prohibiting the CIA from conducting disinformation campaigns on U.S. soil.

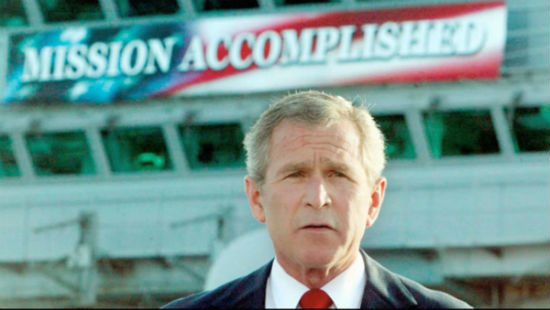

Well, yeah, that was illegal, and exactly the kind of high crime the founders had in mind when they invented impeachment. So normally, in a healthier democracy, that would be a big deal. But ours isn’t a healthy democracy, and the Bush administration has committed — and admitted — so many of those that one more hardly seems like news. This is a president, after all, who brags about warrantless wiretapping on American citizens.

So, yes, if you’re still thinking that laws and the Constitution and conventional morality somehow still apply to this bunch, then you should check out Suskind’s book for a fine summary of the prosecution’s slam-dunk case for impeachment.

But that’s not my main point here. My complaint here is slightly different: This particular crime, this forged letter and disinformation campaign conducted against the American people, was too late to do any good. Manufacturing a pretext for war only works if it’s done before the invasion occurs.

I’m not saying I approve of this kind of criminal deception. It’s sleazy, illegal and just plain wrong. Manufacturing a false pretext for war is Very Bad. It is only done when the war in question doesn’t have an actual pretext, which is to say when the war was not actually necessary. So we’re talking about making up lies to excuse sending young people to kill and die when they didn’t need to do either. Very, Very Bad.

But it’s not the worst alternative. The worst alternative is what the Bush administration chose to do instead: Assert it’s right to go to war without a pretext. The former is the action of an outlaw government. The latter is the action of a lawless government. If forced to choose, I’ll take the outlaw over the the lawless every time. Neither choice is good, but we’d still be better off being governed by people who break the law than by people who glibly dismiss the very idea of law itself.

When it came to the invasion and occupation of Iraq, the Bush administration took an approach somewhere in between these two Very Bad options of law-breaking and law-abolishing. They manufactured a pretext (several, in fact, some of them contradictory) but they didn’t really put much effort into it. They were intent on breaking the law, but they didn’t much care whether or not they got caught.

Thus we saw poor Colin Powell disgracing himself at the U.N. with white powder from the prop room, drawings of WMD and mistranslated radio intercepts. Powell himself called that PowerPoint presentation “bullshit,” and no one in the room that day found it persuasive. (It dazzled the wide-eyed rubes at The Washington Post editorial board, but that’s not much of an achievement.) The whole effort seemed like the kind of last-minute, half-baked work done by a lazy, careless student. It was just barely enough to provide a fig leaf for members of Congress who had already decided that war would be really, really neat, but for the most part the Bush administration just didn’t seem to care whether or not their false pretexts really seemed credible. They weren’t so much trying to get away with breaking the law as they were trying to demonstrate that, in their view, the law didn’t apply to them.

That was even clearer when it came to the discussion of whether or not the proposed invasion of Iraq was a just war. This was an entirely one-sided discussion. No one who looked at the argument for invasion was able to reconcile this with the jus ad bello criteria of that tradition. So how did the Bush administration — and their many surrogate pundits — respond to this criticism? They didn’t. An outlaw government might have lied, making up reasons why the invasion was justifiable, but this lawless government didn’t bother to do even that. The invasion would not be a just war said everyone from John Paul II to the faculty of the war college and the administration’s response was not to argue that it was, but to say, in essence, “Just war tradition? F— that.“

In that case, at least, they weren’t abolishing an actual law. The just war tradition is only that, a tradition. It isn’t written into the Constitution, nor was it ratified as the law of the land in any of the treaties upholding international law (though it does parallel much of that international law). But it does provide another glimpse of the Bush administration’s tendency to claim that ignoring the rules — whether they be moral traditions or legally binding statutes — is their prerogative.

All of which is why I found it weirdly encouraging, almost, to read Seymour Hersh’s description of an idea being kicked around in a brainstorming session in Vice President Dick Cheney’s office:

HERSH: There was a dozen ideas proffered about how to trigger a war [with Iran]. The one that interested me the most was why don’t we build — we in our shipyard — build four or five boats that look like Iranian PT boats. Put Navy seals on them with a lot of arms. And next time one of our boats goes to the Straits of Hormuz, start a shoot-up. Might cost some lives.

And it was rejected because you can’t have Americans killing Americans. That’s the kind of — that’s the level of stuff we’re talking about. Provocation. But that was rejected.

I’m glad this Tonkinesque scheme was rejected, but I was pleasantly surprised to learn that such a thing was even being considered. This silly false-flag operation was to have been carried out with the explicit purpose of deceiving the American people and the Congress — all of which would have been illegal. But that’s what I find hopeful here: They’re thinking like mere criminals again, like outlaws.

All of that, again, is Very Bad, but not as bad as the alternative of claiming that the law does not apply to them, that the law does not matter, that it can be not just broken, but ignored with impunity. The Bush administration seems to have backed away, slightly, from its agenda of abolishing the rule of law and to have gone back to merely trying to break the law without getting caught. That’s progress.

Sort of.