Mark Benjamin of Salon points out that former Vice President Dick Cheney and retired Gen. Tommy Franks just aren't that bright.

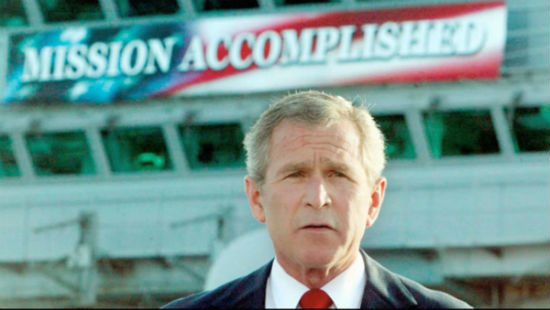

Benjamin didn't put it that starkly himself, but that's the inescapable conclusion. He recently spoke with Bob Garfield of NPR's On the Media about what Franks called the "Dover effect" (see "The True Cost of War"). The occasion for this conversation was the Obama administration's reversal of the policy, in place since 1991, prohibiting the publishing of photographs of flag-draped coffins from Dover Air Force Base. Here's Benjamin on the background and alleged rationale for the former policy:

The original policy was actually written in 1991 by someone everyone’s heard of, Dick Cheney, who at that time was Secretary of Defense. He put that policy in place under the first Bush administration, just on the eve of the first Gulf War, to prevent photographs of those caskets. …

Early in the Bush administration, [Gen.] Tommy Franks coined the term “the Dover effect,” and what he was referring to was he believed that there was only a certain number of images of flag-draped coffins that the American public was willing to see, willing to put up with, before support for a war begins to fade.

Franks' notion of the "Dover effect" was shaped by Vietnam and applied to Iraq. Reflecting on both of those wars, Lt. Gen. William E. Odom suggested a very different lesson: "There is no way to win a war that is not in your interests," he said.

That's not a difficult or a theoretical concept. It's just a simple statement of a basic principle like "Fire is hot" or "water is wet." Yet somehow Franks and Cheney were not — are not — able to grasp this. They still think that the U.S. can win a war that is not in its interest if only it tries really hard. Matt Yglesias calls this the "Green Lantern Theory of Geopolitics" — the notion that anything, even self-contradiction, is possible with sufficient willpower.

"There is no way to win a war that is not in your interests."

You can almost picture Franks and Cheney dimly staring at that written on a chalkboard, trying and failing to comprehend. "I guess what it means," Cheney says finally, "is that it's difficult to maintain public support for a war that is not in your interests." And from there the two men go on to theorize about the "Dover effect" and the best ways to hide the sorts of images that might lead to public protest.

An important corollary to "There is no way to win a war that is not in your interests" is this: There is no way for a just nation to win an unjust war. Franks and Cheney, like all adherents of the Green Lantern Theory, can't tolerate the idea of just and unjust wars. The just war tradition arose as an effort to restrain evil and suffering. Such restraint, these willpower worshippers believe, inhibits the unrestrained force of will required for victory. In the words of the leading philosopher of this movement, all such restraints lead to a scenario in which "Somebody wouldn't let us win."

But while the just war tradition is primarily concerned with morality, that is not its only function or benefit. For the purposes of our discussion here, the just war tradition is less important as a means of restraining evil and suffering and more important as a means of restraining self-defeating and counterproductive stupidity.

Appreciate that Franks' notion of the "Dover effect" only makes sense if one believes that war is an option — a choice that a supposedly fickle and weak-willed public may choose to stop choosing.

If this were actually the case — if a given war really were optional, then it would also be a war that we should not have been fighting in the first place. It would be, in other words, an unjust war. And, therefore, it would be a war that a just nation cannot win — a war for which "victory" is not one of the possible outcomes.

This is true regardless of public opinion. No amount of public support can make an unjust war winnable.

And just as an unjust war is unsustainable, with or without public support, so too protest against a just war tends to be unsustainable, with or without success on the battlefield.

Consider the basic criteria for what constitutes a just war: a just cause/redress of wrong (not merely that a wrong has occurred or exists, but that this particular action — i.e., war — will redress that wrong); right intention; legitimate authority; last resort; probability of success; proportionality.

A just war must meet all of those criteria. When that is the case, the images of flag-draped coffins at Dover tend to reinforce and redouble the public's support.

A unjust war is any that fails to meet one or more of these criteria. When that is the case, public sentiment will turn against it no matter how well you hide the wounded and dead or how many flags you wave. And this will not happen because the public is weak-willed or fickle, but because the public will correctly conclude, eventually, that any cost is too high for an unjust and therefore unwinnable war.

Take those principles one by one and this becomes clearer.

If a given war is demonstrably due to a just cause/redress of wrong, then the public will tend to support it. You'll still have conscientious objectors and pacifists, of course, but they'll be more likely to be driving ambulances and rolling bandages than to be organizing sit-ins or marching in the streets.

If a given war is demonstrably the last resort then not only is widespread public opposition unlikely, such opposition is moot. Such opposition would mean calling for an alternative that has been shown not to exist.

(The trickiest of these principles for what we're discussing here may be the matter of legitimate authority, about which more later.)

The impulse to hide the cost of war from the public is an indication that the war in question is unlikely to receive the support of the public. It is an indication, in other words, that the public is likely to recognize that the war is not in its interest — and that it is unjust.

Attempts to deceive the public into supporting such a war may succeed in the short term, but that won't matter one way or the other when it comes to the outcome of such a doomed and counterproductive war.