One of the common, but strange, responses to Rob Bell’s infamous lack of enthusiasm for eternal torture has been what we might call the Missiological Case for Hell.

This case was articulated recently by Russell Moore, dean of the school of theology at Southern Seminary, during a Team Hell Strategy Session at Al Mohler’s Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in Louisville, Ky. The (Southern) Baptist Press summarizes Moore’s remarks on the Missiological Case for Hell:

Bell’s view of salvation, Moore said, is wrong biblically but also flawed practically and will lead to empty church pews. If the pastor says there is no judgment and everyone will end up in heaven, then people have little motivation to follow Christ, Moore and the other panelists said.

“You never have a universalist Great Awakening,” Moore said. “… The very thing [Rob Bell] is attempting to do, it never succeeds. You always wind up losing the church and unable to reach the people outside the church.”

Moore says the church will collapse without the threat of judgment. And, to be clear, “judgment” must mean nothing less than the vast majority of humankind suffering consciously for eternity in the Hell that Moore, et. al., imagine (magical fire, merciless God, “holy” as synonym for “sadistic,” etc.). Without that threat, Moore says, there can be no revival, no evangelism, no missionary outreach, no church growth. Without Hell, the church will shrink and shrivel and fade away.

This is hogwash.

I don’t mean “I think, in my opinion, that this is hogwash,” I mean that Russell Moore thinks, in his opinion, that this is hogwash. Or he would have if he had thought this through, because the silliness he’s advocating here slanders the church and all of its members, including himself. Russell Moore is unjustly impugning the motives of Russell Moore and maliciously accusing Russell Moore of believing things that Russell Moore does not believe.

The embrace of the Missiological Case for Hell represents a shift in the argument of Team Hell that Moore acknowledges here. The doctrine of Hell, Moore argues, is “practical.” It is useful. It works. That is a much lesser claim than the assertion that the doctrine of Hell is true. And it’s a much lesser claim than the assertion — which Moore presumes, without support — that the doctrine of Hell is something the Bible teaches.

What neither Moore nor his colleagues on the Team Hell panel discussion seems to notice is that this panel discussion was explicitly organized because they all believe that Moore’s “practical” argument is not true. The panel was called together, Al Mohler says, because of Rob Bell’s tremendous popularity. “He has a tremendous influence, especially with younger evangelicals, and I think that’s why we have to talk about this,” Mohler said at the outset of the discussion.

This is why this panel of Team Hell luminaries was there in the first place, because people are packing the pews at Rob Bell’s church and because his “Love Wins” message is reaching more and more people inside and outside the church.

So Moore shows up for a talk in response to the growing popularity of a movement producing explosive church growth and dramatic outreach, and then proceeds to say that this movement is wrong because it is unpopular, it will shrink churches and end outreach. Bell’s ideas are wrong because they will lead to empty pews, which is why Bell must be stopped from filling the pews by preaching those ideas. Or something like that. If Moore can’t be bothered to make sense of what he’s saying then it’s unfair to expect the rest of us to make sense of it for him.

In any case, I haven’t time here for a full refutation of the Missiological Case for Hell, but let’s just quickly look at three counter-examples — three “practical” case studies — that cast doubt on this whole notion of the missiological and ecclesiological usefulness of a doctrine of Hell.

Case Study No. 1: Paul

The enthusiasts of Team Hell would likely agree with me that St. Paul was a very successful missionary. We could attribute his success to the work of the Holy Spirit, or we could credit it to Paul’s sharp wits and dogged determination, but one thing that no one can possibly argue is that Paul’s success as a missionary was due to his preaching about Hell and his stern warning of the certainty of future, eternal, conscious torment for unbelievers.

Paul never gave such a warning. Never. Like all of the other apostles and missionaries and early church leaders portrayed in the book of Acts, Paul never spoke of Hell. Paul’s gospel made no mention of Hell.

And yet his listeners seem to have found far more of a “motivation to follow Christ” than any of the fearful followers of the missionaries of Team Hell. Paul’s listeners seemed to understand the gospel that he preached as good news that was actually good news.

As Rob Bell points out, the unbiblical substitute for that good news promoted by Team Hell is not really good news at all. If the good news is primarily that some few have a chance to escape the otherwise inevitable fate of conscious, eternal torment, then this message isn’t really news that most people will hear as good. And in any case, this is not the gospel that the Bible teaches. That gospel — the good news of God crucified, risen and triumphant over sin and death — is proclaimed repeatedly in scripture, but never is it presented as How To Escape Eternal Torture in Hell. The accusation that Team Hell loves to level at people like Bell — that it is callous and irresponsible not to confront the damned unbelievers with an explicit warning of the Hell that awaits them — can and must be applied even more strongly against Paul, Jesus, Matthew, Mark, Luke, John, Q and all the apostles of the early church as portrayed in Acts.

Case Study No. 2: Russell Moore.

I don’t know Russell Moore, dean of the school of theology at Southern Seminary. I have never met him. But I know this much about him: Russell Moore is not a Christian because of the fear of eternal, conscious torment in Hell.

Moore believes that if he were not a Christian, then he would be destined for such eternal, conscious torment. And yet that’s still not the main reason he is a Christian. It’s not one of the top five reasons. Or the top 10.

Again, I don’t know Moore and I have never heard him tell the story of his own faith, but I know this is true for him because it is true for everyone who is a Christian. Get Moore away from the microphone and away from his official duties as a Defender of the Doctrine of Hell and then ask him why he is a Christian and I don’t know specifically what he would say, but I know generally. He would speak of God’s love for him and of his love for God. He would tell you about faith and hope, grace and gratitude, meaning and purpose. He would tell you about the love that was shown to him by some devout disciple or group of disciples and about the inspiring examples of good people he has known. He may say something about Heaven, but mainly in the context of God’s great love and the longing to experience that love as directly as possible. He may tell you some story of some numinous personal experience that he will apologize for being unable to articulate. He may tell you about his parents and grandparents.

But he won’t talk about Hell. If he mentions it at all, it will be as an afterthought — as though being rescued from the certainty of eternal torture was just a fringe benefit of all the rest, an added bonus.

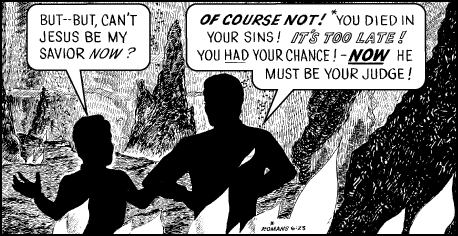

I do not know anyone who is a Christian because of the fear of eternal torment in Hell. I know several people who used to be Christians, briefly, because someone had taught them this idea of Hell and that becoming a Christian was the only way to escape certain torture. But none of those folks were happy or proud about having made that decision for that reason, and it didn’t last. The preacher or teacher who had so vividly described the invisible and eternal gun to their head didn’t turn out to have much lasting influence.

I suppose there are congregations where the preacher invokes that invisible threat week after week, twice on Sundays and again on Wednesday nights. And I suppose something might arise in such congregations that might seem like a passable imitation of love for God, or that might feel like a functional substitute for belief that God loves us. But that’s not love, or faith, or discipleship. That’s Stockholm syndrome and it, too, will fade once the hostages are safely distant from the constant stress of the coercive threat.

Which brings us to our final case study.

Case Study No. 3: Saddam Hussein

The Missiological Case for Hell reminds me of one of the stranger stories about Saddam Hussein, the late and unlamented dictator of Iraq. Saddam ruled through fear but, at some level, he wanted his terrified subjects to love him.

We know that Saddam wanted their love — uncoerced, untainted by fear — because he wrote a novel and released it secretly under a pseudonym. The love and acclaim the people would pour out for this anonymous author, the dictator hoped, would be genuine and voluntary and he would at last know what it meant to be loved in truth and not just to have others falsely proclaim their love for him out of fear of torture and death.

But alas, the novel was apparently awful. It was panned and mocked and it did not sell.

That was intolerable for the tyrant, so he leaked the true identity of the author. Suddenly all the critics who had found it wanting recanted, lavishing it with forced praise. It became a best-seller in Iraq, but only in Iraq — only in the one country where people were forced, out of fear and the threat of torture, to pretend that they loved a man they actually despised, a man who deserved to be despised because of those very threats of torture.

Saddam published several more novels — all in his own name. They received massive critical acclaim and commercial success, but only within his realm. The Iraqis’ love for Saddam’s novels — like their love for Saddam himself — was a charade. And Saddam knew it was a charade. But he embraced that charade because it was the best he could hope for, because it was more than he deserved. For the despicable tyrant, feigned affection at gunpoint was preferable to the genuine contempt it masked.

God desires something better than that. And God deserves something better than that.

Even Saddam Hussein knew that love is not real if it is coerced under threat of torture. If fear and loathing masquerading as love could not fool Saddam Hussein, then you can be sure it does not fool God either. That is not what God wants from us. God wants our genuine love, freely given.

Why, then, would anyone think that God had arranged the universe in such a way as to guarantee that God would never be able to receive genuine love, freely given, but only a fearful, coerced imitation? I believe that God is good and I believe that God is smart — too good and too smart to confuse coercion with love.

Unlike the advocates of the Missiological Case for Hell, I believe that God is better and smarter than Saddam Hussein.